Testimony of Gary Milhollin

Professor Emeritus University of Wisconsin Law School and

Director, Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control

Before the Committee on Armed Services

United States House of Representatives

September 19, 2002

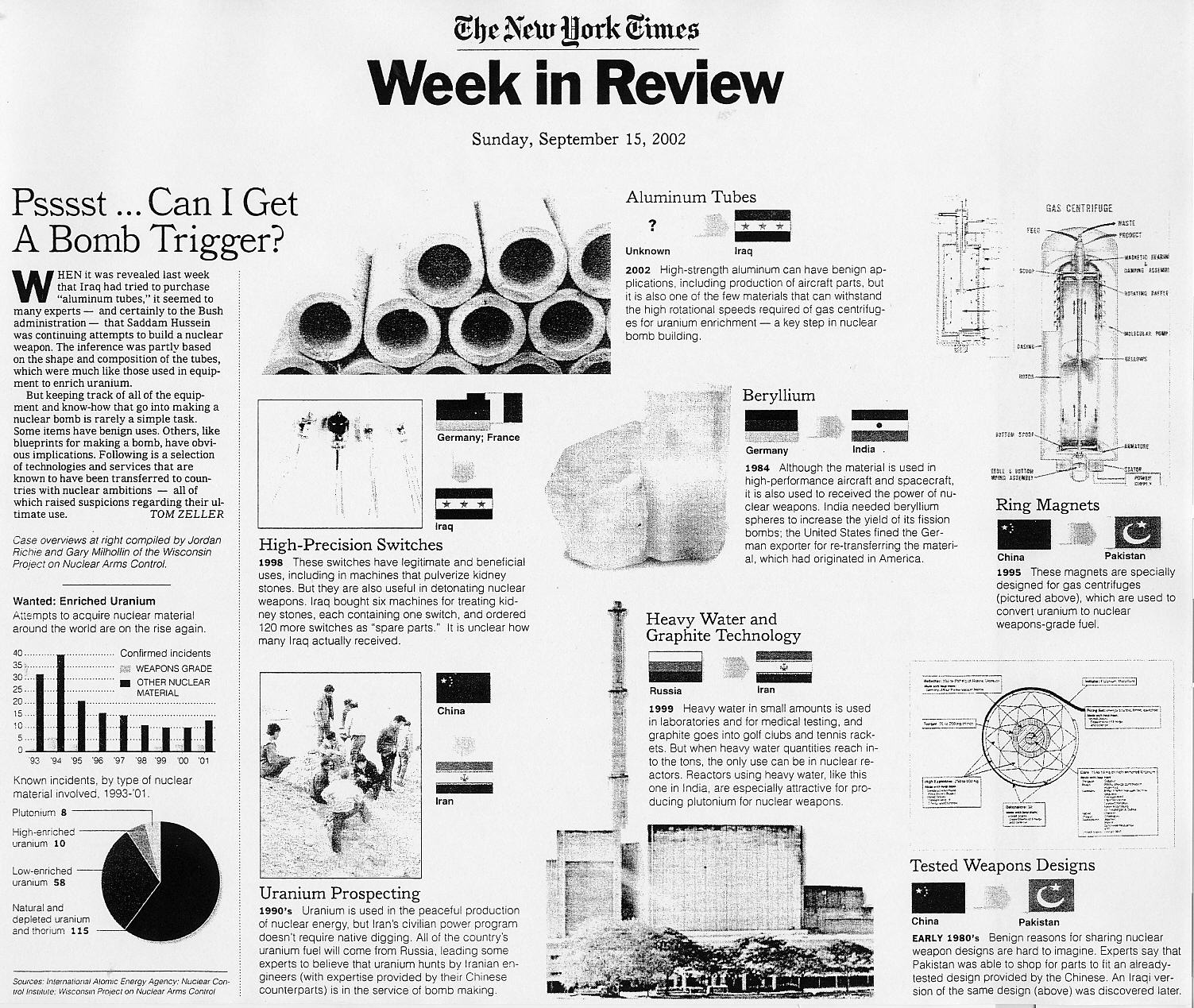

I am pleased to appear today to discuss the threat from Iraq’s mass destruction weapon programs, and the relation between that threat and the export of sensitive technology. Before getting into the substance of my testimony I would like to offer some items for inclusion in the hearing record. First, there are two recent articles written by my organization on inspections in Iraq, one from the New York Times and the other from Commentary magazine, together with a graphic prepared by my organization for the New York Times Week in Review that describes a series of dangerous nuclear imports and what one can learn from them. Second, there is a list of addresses in the United States where one can buy high-strength aluminum tubing similar to that recently intercepted on its way to Iraq.

I would like to begin by simply affirming that Iraq does have active programs for building weapons of mass destruction. We know that Iraq has a workable nuclear weapon design and lacks only the fissile material to fuel it. We also know that Iraq has recently tried to import high-strength aluminum tubing that our government says is suited to making centrifuge components which, in turn, are used to process uranium to nuclear weapon grade. Iraq also has an active program for making long-range missiles, and we know that Iraq has produced and weaponized nerve gas, mustard gas, and anthrax. In addition, we know that Iraq’s procurement activities have continued throughout the 1990’s despite the U.N. embargo.

The current status of these programs is summarized in my organization’s website: www.iraqwatch.org. I invite the Committee to consult this site to obtain a continuously updated report on what we know about Iraq’s mass destruction weapon efforts.

It is an unfortunate fact that Iraq has built these programs almost exclusively through imports. The great majority of these imports were from the West, and most of them were sent legally. Weak export controls were primarily to blame.

In February of this year, I had the privilege of testifying before this Committee on the new Export Administration Act, which is now under consideration by Congress. I made the point that this bill was conceived in a bygone period of history – the days before September 11, 2001. In reaction to the attacks on September 11, one would expect the United States to search for ways to strengthen controls on the sales of dual-use items. These sensitive products are the ones that terrorists and terrorist-supporting nations need to make weapons of mass destruction. Instead, we are going in the opposite direction. The bill now being considered would authorize the Commerce Department to drop export controls on the very items that our enemies would most like to use against us.

For example, I would like to draw the Committee’s attention to the shipment of high-strength aluminum tubes that was intercepted recently on its way to Iraq. According to administration sources that were quoted in the press, the tubes could have been used to make gas centrifuges, which can process uranium to nuclear weapon grade. President Bush cited the shipment as evidence that Saddam Hussein still has an active nuclear weapon program.

If the bill now being advocated by the administration passes, however, these very tubes would be removed from export control. They meet the bill’s proposed criteria for “mass market” items as well as for “foreign availability.” For this reason, they could be decontrolled by the Secretary of Commerce acting alone.

Such a decontrol would mean two things. First, the United States would no longer be able to interdict such shipments. We could never ask foreign countries to stop selling something that our exporters were entitled to sell without restriction. Thus, countries like Iraq would have a much easier time importing the means to make nuclear weapons.

Second, the Bush administration would be preparing to go to war to prevent Iraq from importing an item that the administration had decided was not important. This would damage our international credibility just when we need it most. We can’t cite Iraq’s appetite for aluminum tubes as justifying an attack or an ultimatum on inspections, and at the same time say that such tubes qualify for decontrol.

This week, the staff at my organization investigated the commercial availability of high-strength aluminum tubes. The staff identified numerous U.S. sellers of these tubes who were ready to take our order for as many tubes as we wanted to buy. It requires roughly a thousand of these tubes, made into centrifuge components, to produce enough weapon-grade uranium for one bomb per year. Our staff could have purchased several thousand of these tubes from a number of sellers here in the United States. I have attached a list of these outlets to my testimony.

It is clear that this wide availability within the United States would qualify the tubes for “mass market” status under the proposed bill. As a result, the Secretary of Commerce would be required to free them from export control. The criteria for mass market status are as follows:

- The item must be “available for sale in a large volume to multiple purchasers;”

- The item must be “widely distributed through normal commercial channels;”

- The item must be “conducive to shipment and delivery by generally accepted commercial means of transport;”

- The items “may be used for their normal intended purpose without substantial and specialized service provided by the manufacturer.”

High-strength aluminum tubes meet all of these criteria, which are listed in Section 211 of the bill. The bill says that the Secretary of Commerce shall determine that an item has mass market status if it meets them. The items would then be decontrolled automatically.

There is something wrong with this picture. What is wrong is that the world has changed, and this bill does not reflect that fact. How can we free for export something we are accusing the Iraqis of importing to make atomic bombs? It is manifestly absurd to decontrol the same technologies that we are worried about Saddam Hussein importing. With one hand, we would be helping Iraq make nuclear weapons, and with the other we would be smashing Iraq for doing so.

High-strength aluminum tubes are not the only items that are useful in making centrifuge parts. Maraging steel and carbon fibers are also employed for this purpose. Iraq experimented with both of these items when it tried to build centrifuges. As it turns out, both maraging steel and carbon fibers also meet the “mass market” criteria in Section 211.

In addition to centrifuge components, maraging steel is used to make solid rocket motor cases, propellant tanks, and interstages for missiles. In 1986, a Pakistani-born Canadian businessman tried to smuggle 25 tons of this steel out of the United States to Pakistan’s nuclear weapon program. He was sentenced to prison as a result. Maraging steel has been controlled for export since January 1981.

This steel is produced by companies in France, Japan, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, and it meets all the criteria for “mass market status.” Several steel companies list maraging steel on the Internet and can produce it in multi-ton quantities. Over the telephone, two American companies and one British company explained to my staff how to order 25 ton quantities with delivery in less than a month. Maraging steel is bundled and shipped much like stainless steel, which it closely resembles.

In addition to maraging steel and high-strength aluminum, composites reinforced by carbon or glass fibers can be used to form the rotors of gas centrifuges. The fibers are also used in skis, tennis racquets, boats and golf clubs, and are produced in a number of countries. This availability would give the fibers “mass market status” under the bill, despite the fact that they too have been controlled for export since 1981.

In addition to the “mass market” criteria in the bill, these three sensitive items would also meet the “foreign availability” criteria. These are equally sweeping. The include any item that is:

- “Available to controlled countries from sources outside the United States;”

- “Can be acquired at a price that is not excessive;”

- Is “available in sufficient quantity so that the requirement of a license or other authorization with respect to the export of such item is or would be ineffective.”

As I testified before this Committee in February, this language is so broad that it would appear to cover North Korean rocket motors. It would also cover the aluminum tubes we are worried about. We know that the tubes did not come from the United States; thus, they were obviously available abroad.

The only way to retain control over the sale of these items is for President Bush himself to make a special finding within 30 days, in which he would set aside the Commerce Department’s decision. This is an authority that he is not allowed to delegate. In effect, the bill sets up a powerful new machine at the Commerce Department for decontrolling exports. As I testified in February, once that machine gets moving, it is going to chop big holes in the existing control list unless the President can find some hours in his schedule in which to undo the Commerce Department’s work. Do we really want the President of the United States to put aside his concern about Osama bin Laden, or about the economy, and spend his time thinking about aluminum tubes, maraging steel and carbon fibers?

This is not an academic question. American lives are threatened by dangerous exports. We are now sending pilots, almost every day, to bomb Iraq’s air defenses. U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, speaking to the press on Monday, reminded us that those defenses use fiber optic technology installed by Chinese companies, one of which, Huawei Technologies, was virtually built with American technology. China’s assistance to Iraq was not approved by the United Nations, and thus violated the international embargo.

The history of Huawei shows how sensitive American exports can wind up threatening our own armed forces. At about the time when this company’s help to Iraq was revealed last year, Motorola had an export license application pending for permission to teach Huawei how to build high-speed switching and routing equipment – ideal for an air defense network. The equipment allows communications to be shuttled quickly across multiple transmission lines, increasing efficiency and reducing the risk from air attack.

Motorola is only the most recent example of American assistance. During the Clinton Administration, the Commerce Department allowed Huawei to buy high-performance computers worth $685,700 from Digital Equipment Corporation, worth $300,000 from IBM, worth $71,000 from Hewlett Packard and worth $38,200 from Sun Microsystems. In addition, Huawei got $500,000 worth of telecommunication equipment from Qualcomm.

Still other American firms have transferred technology to Huawei through joint operations. These included Lucent Technologies, which agreed to set up a joint research laboratory with Huawei “as a window for technical exchange” in microelectronics; AT&T, which signed a series of contracts to “optimize” Huawei’s products so Huawei could “become a serious global player;” and IBM, which agreed to sell Huawei switches, chips and processing technology. According to a Huawei spokesman, “collaborating with IBM will enable Huawei to…quickly deliver high-end telecommunications to our customers across the world.” Did IBM know that one of these customers might be Saddam Hussein?

These exports no doubt make money for American companies, but they also threaten the lives of American pilots. Indeed, as we now contemplate military action against Iraq, we seem to see history repeating itself. During the Gulf War, the United States was forced to send pilots on missions to bomb plants filled with equipment that American and other Western companies had supplied. Some of those pilots did not come back alive. So, when we talk about export controls, we are not just talking about money. We are talking about body bags.

I would like to submit for the record some articles I wrote for the New York Times back in the early 1990’s, together with a report entitled “Licensing Mass Destruction.” These publications list the dangerous exports that American and Western companies sold to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq before the Gulf War. It is safe to assume that many of these products are still helping Iraq’s mass destruction weapon efforts and have never been found by the U.N. inspectors.

In the article in the New York Times from 1992, entitled “Iraq’s Bomb, Chip by Chip,” we see that America’s leading electronic companies sold sensitive equipment directly to the Iraqi Atomic Energy Commission, to sites where atomic bomb fuel was made, and to a site where A-bomb detonators were made. American companies also shipped directly to Saad 16, Iraq’s main missile building site, and to the Iraqi Ministry of Defense, which oversaw Iraq’s missile and A-bomb development. Virtually every nuclear and missile site in Iraq received high-speed American computers.

These exports are set out in greater detail in our 1991 report “Licensing Mass Destruction.” The report shows that all of these exports were licensed by the U.S. Commerce Department and, in many cases, the Commerce Department knew full well that the exports were going to nuclear, missile and military installations. Why did the Commerce Department approve such exports? Because the United States was following a policy of putting trade above national security. The bill now before Congress follows this same policy. That policy was wrong then, and it is just as wrong now.

The second article in the New York Times is from 1993. It shows that America was not alone in supplying Iraq’s mass destruction weapon effort. Its Western allies joined in. Germany (then West Germany) was far and away the leading culprit. German firms sold as much to Iraq’s mass destruction weapon programs as the rest of the world combined. Not only were German firms the main suppliers of Iraq’s chemical weapon plants, German firms also sold components that helped increase the range of Iraq’s Scud missiles. These longer-range Scuds were able to reach Tel Aviv, where they killed Israeli civilians, and Saudi Arabia, where they killed American troops. I must say that I find it shocking that Germany, whose companies have done more than any others to create the mass destruction weapon threat from Iraq, is apparently less willing than any other Western country to confront it.

My point in this testimony is that since September 11, we can no longer afford to put trade above security. We must convince the rest of the world to keep the means to make weapons of mass destruction away from terrorists and the countries that support them. Yet, we can never do that if we free our own companies to sell these same technologies. We can’t have it both ways. Either we protect ourselves from terrorism, or we make a few more bucks from trade.

AVAILABILITY OF HIGH-STRENGTH ALUMINUM TUBING

September 19, 2002

During the week of September 16, 2002, the Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control conducted a study of the availability of high-strength aluminum tubing in the United States. The Wisconsin Project identified numerous suppliers of 7000 series tubing, in particular series 7075, which is one of the kinds needed for centrifuges and meets the criteria for dual-use export controls administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce. An export license is needed if the tubes fit two criteria: an outside diameter of at least 75 mm (three inches) and a tensile strength capable of 460 Mpa or more at 293K (20 degrees C).

The Wisconsin Project identified the following suppliers, who offered to supply thousands of tubes meeting the control criteria within a period of roughly two months:

- Alcoa Aluminum Company (Lafayette, Indiana; 800-443-4912 ext. 3007)

- TW Metals (various locations throughout the United States; 800-545-5000)

- Metals Unlimited (Longwood, Florida; 800-782-7867)

- Metalsource (Chattanooga, Tennessee; 800-487-6382)

- Specialized Metals (Coral Springs, Florida; 954-340-9225)

- Kaiser Chandler (Richland, Washington; 866-249-3421)

In addition to the above firms, which the Wisconsin Project contacted individually, a number of others advertise high-strength aluminum alloys on the web. Some of these firms specifically offer alloys that meet the control criteria in their product descriptions. The Wisconsin Project will supply the names of these firms upon the Committee’s request.