A Round Table Discussion

Thomas Donnelly, AEI

Reuel Marc Gerecht, AEI

Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, AEI

Gary Milhollin, Wisconsin Project on Arms Control

Moderator: Danielle Pletka, AEI

March 4, 2003

MS. PLETKA: [In progress] — meeting in northern Iraq. They appointed a leadership council that included (?) , Kurds and others. And doubtless there are going to be more developments later in the week.

We’re awfully happy to have with us today–I’m going to go in alphabetical order–Tom Donnelly, who is AEI’s resident fellow, and he’ll talk about military preparations and a little bit about Turkey, I think.

We have Reuel Gerecht, also a resident fellow at AEI, who’s going to talk a little bit about Iraq’s Shi’a and Shi’a inside Iraq and outside.

We have Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick, who’s AEI’s senior fellow, to give us some insight into the United Nations.

And we have our guest, Gary Milhollin, who is the director of the Wisconsin Project on Arms Control, to talk a little bit about weapons of mass destruction, where they are, what they might be, and what we might find.

Thank you all. We’re going to go in alphabetical order this morning. As is our practice, each of our speakers will speak for five to ten minutes, and we will go from speaker to speaker, and then we will open it for questions.

Thank you very much. Tom?

MR. DONNELLY: Thank you, Dani.

As Dani said, I’m going to talk primarily about sort of where we are militarily. I will resist the temptation to speculate too much about Turkish domestic politics, but apparently the Turks are going to be given another chance to do their homework properly, if not today then fairly soon.

In addition to where we are in the deployment for war, where we are on the road to war, I’m going to talk a bit about the controversy about post-war occupation and troop levels that have come up in the past week. But let’s begin with deployment status, so to speak.

There’s been a lot of speculation as to precisely how big a monkey wrench would be thrown into the works if there’s not a second front operation that goes through Turkey, a lot of commanders arguing that it won’t make a decisive difference. My own view is that that’s probably correct, but it will certainly slow things down and make it more difficult to seize the important political targets in the north, particularly the oil fields and the city of Mosil and other important spots in the north.

In terms of how fast we will get to Baghdad, I think that may be the key reckoning in the commanders’ judgment, and, again, I think you can sort of judge from the shape of the deployments that the primary assault on Baghdad will come mostly from the south.

It’s a little known fact that there was as plan to go to Baghdad sort of drawn up very hastily after the conclusion of the first Gulf War when it was uncertain about the outcome of the peace negotiations and whether Saddam was going to sign on to the UN resolutions, which he did technically sign on to but which, of course, he has not fulfilled.

And there was actually a reasonably detailed plan that was drawn up to sort of surround Baghdad and then, if necessary, go into the city, which was done basically–again, if you remember the situation at the time, American forces were essentially on the Euphrates River and within sort of a one-day hop by helicopter and a shorter road march from the river to the sort of suburbs of Baghdad. And, again, I will not go through the history of that in extensive detail, but, again, sort of because geography is essentially the same and we’ll be employing many of the same systems that we had at that time, I think we can expect to see some sort of generally similar operation.

And perhaps the most notable deployment effect of the last 24 hours has been the embarkation of the soldiers of the 101st Airborne from the United States to marry up with their equipment, which is shortly to be unloaded in Kuwait.

While the plan per se is likely to have a number of aspects in it, I would argue that the 101st is going to be a key to any plan, depending on what variant we actually carry out. And that’s something that people should be watching over the next week or so to see how the unloading and the arrival of the 101st goes in Kuwait and how quickly they can sort of get to their line of departure, and you can see that the diplomatic and military deployment timelines are beginning to come together.

So while certainly General Franks and his staff and all the people in the Pentagon are hoping for a good outcome from the Turkish parliament sometime very quickly, because it will be necessary, obviously, to offload the boats that are bobbing around in the harbor of Iskenderun and get them up country, I think we can expect that to go pretty quickly once the green light is given by the Turks. And, in fact, it’s conceivable that under certain circumstances we would essentially roll right off the boat and directly into combat-like operations.

So, again, I would tend to regard that as a subsidiary part of the larger attack and that this is obviously a very-nice-to-have outcome in terms of a positive vote from the Turks, but not something that is necessarily going to delay the initiation of combat operations. Again, just sort of putting the commentary of the last 24 hours, looking at it from my perspective, I think the delay has been overemphasized there.

So once the diplomatic dance about the vote in the UN is concluded, or not concluded, but when it comes to a termination as advertised by the end of next week, I think it’s reasonable to say that at that point military operations certainly could begin without a whole lot of handicaps.

Finally, I want to just talk briefly about the controversy over the size of the American post-war garrison or deployment. The Chief of Staff of the Army said about a week ago that it would require several hundred thousand troops, sort of indefinitely. He was immediately contradicted by the Deputy Secretary of Defense. I am not going to try to referee that controversy. I do want to try to put it in some sort of perspective, however.

Again, if you sort of forced me at gunpoint to say he was more likely to be correct, I think that recent history would suggest that Secretary Wolfowitz may be more likely to be correct and that General Shinseki is quite rightly being cautious and conservative, but especially the analogy to the Balkans that has been elicited out of that is perhaps overdrawn–the important distinction being, of course, between the strategic and political framework that American forces and NATO forces were operating within in the Balkans, which was essentially separating factions at war and, as we’ve seen since then, ambiguity about the larger political and strategic outcome that we wanted to achieve in the Balkans. We have not exactly achieved regime change in the Balkans the way that we say we are going to in Iraq. So if we certainly ended some of the–or ended the slaughter in the Balkans, we have not exactly put the Balkans on the road to a multi-ethnic, self-governing democracy. And, of course, that’s what we’re trying to do and what we will intend to do and I believe what we’ll be able to accomplish in Iraq. And so we will be sort of moving in the direction that the majority of Iraqis themselves want to go in. And the job of American forces is to secure that, to allow a political dynamic that’s been developed not only inside Iraq but outside Iraq for the past decade, to proceed forward, to assist the Iraqis in going in the direction that the majority of Iraqis want to go with and to clear the way to de-Ba’athify Iraq and, again, to provide a secure environment for a more natural process of political liberalization to go forward.

And there is every reason to believe that not only do we have–first of all, we have a clear objective that we’re trying to achieve, and, second of all, it is an objective that, again, is shared, if not by everybody in Iraq, then by a large portion of the Iraqi pl.

So the job of separating factions that are still at war, as we must continue to do in the Balkans, although the shooting is not going on, there’s no imminent political resolution, does not obtain–certainly we hope not, or it certainly will be a measure of our failure if we find ourselves in a situation analogous to the Balkans five or eight years after the cessation of combat where we have not achieved a larger political resolution inside Iraq. And if that’s the case, it will take a lot more troops, but more broadly, it will be a failure to achieve our political and strategic objectives.

So in trying to judge what the post-war obligation of the United States is going to be, you have to keep in mind the larger measure of success that we’re trying to achieve there. And that’s the way to try to put a frame around the question of just how large the garrison’s going to be, how long the military commitment is going to continue, and what level of operations and hostility we will meet from Iraqis should we go in.

And I’ll stop there and turn it over to whoever is next in the alphabet.

MR. GERECHT: Once the war starts and our attention moves away from Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan–and I think our attention will remain there at least for the first few days of the war because Iraqi Kurdistan does have the possibility to deal us a rather serious curve ball if the Kurds act or react in a certain manner to Turkish actions.

Now, if no problems happen up there–and I tend to be of the mind that I think the Turks will probably behave. They will, I suspect, undoubtedly go into Iraqi Kurdistan. It is understandable that they would do so, but I do not think they are going to make any type of mad dash for Kirkuk. After all, the primary Turkish objective is to have fewer Kurds, not more.

But assuming that things go right up there and those two parties do not go into any type of collision course, I think our attention will immediately shift to where it will inevitably remain, and that is on the Iraqi Shi’a, who represent–numbers are always tricky in the Middle East, but they probably represent somewhere between 60 and 65 percent of the population in Iraq. They have been for decades the preeminent cultural and intellectual force in that country, and they will soon become the undeniable political force in that country. And that’s the thing you have to remember, is that what we are going about ready to do is that we are going to overturn essentially the hundreds of years old Ottoman order, and that for the very first time, the Mesopotamia, Iraq is going to be dominated by the people who actually represent the vast majority of the population.

And it’s important to remember because I think it actually has a lot to do with possible political scenarios. And I would argue on this one that, in fact, the default choice here, the one that is actually the easier way to go, is the democratic choice, because you really are not going to have a military option. I’m not sure how many individuals in the U.S. Government actually believe there is the possibility of defaulting to some type of military strong man, Sunni strong man. But it’s just simply not going to happen.

Once the Shi’a throw off the Ba’ath and the Ba’ath Party–and there are members, absolutely there are members, Shi’ite members in the Ba’ath Party. Do not forget that. Ba’athism has decayed and is simply now more or less a satrapy of Saddam Hussein’s whim. It was at one time sort of a pan-Arab idea. It was a combination of national socialism and communism. And it had certain appeal to some Shi’ites. It really doesn’t anymore, and you are going to–inevitably you will not see many Shi’a clinging to the idea of any type of Ba’athi-directed state, whether that be second, third tier, fourth tier Ba’athi, it’s finished.

I think what you will see–now, it’s difficult to see where there’s going to be quick leadership in the Shi’ite society. I think it is fair to say that the Shi’ite identity has gone up significantly under the regime of Saddam Hussein. It stands to reason that when you have a totalitarian society that you detest and you loathe, you immediately withdraw and seek refuge in an identity that gives you some comfort, solace, and brotherhood, and that is unquestionably Shi’ism.

I suspect that Shi’ite fundamentalist movements in Iraq may have some type of political throw weight. It’s difficult to tell. I don’t actually think that the group that is located in Iran, SCIRI, Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, headed by Al-Hakim, is probably going to be a major player. We’ll have to see. I say that essentially for two reasons: one, Al-Hakim has the charisma of a toadstool; and as a general rule for Shi’ite divines, they should have some type of charisma.

I don’t think–now, he has to some extent advantage in that the clerical hierarchy in Iraq has sustained enormous damage. If you make a comparison, for example, with clergy under the Shah, the Shah more or less left the clergy alone. He did not interfere with the way they operated. He did not interfere with the way really they ranked each other. Saddam Hussein interfered all the time. He imprisoned people without hesitation. He killed senior clerics. He intimidated the hell out of them.

But I do suspect that what you will see, I think the clergy will actually probably bounce back fairly quickly, and you will see the disciplines of Hoyi (ph), who was one of the greatest, certainly the greatest of the more recent Iraqi grand ayatollahs. I suspect his disciplines, who actually are very important inside of Iran, will also be very important inside of Iraq.

Now, what role the clergy actually will have over the majority of Iraqi Shi’a is very unclear. It is entirely possible that a significant chunk or certainly perhaps a telling chunk of Iraqi Shi’ite society in the cities has been sufficiently secularized that, in fact, the allegiance to various clerics may not be important. It may. But I don’t think an organization like CFE, which really doesn’t have a significant following inside of the country, which has, as I said, a leader whose overall appeal certainly doesn’t keep you awake long, is probably going to have a lot of pull.

Also, SCIRI really is a public organization. It’s not a clandestine organization. So, you know, if when they come into the country, as they may come in, the Badr Brigade, which is their military brigade, may come into the country, but, I mean, they can’t hide. Everybody knows who they are. It’s not like the other more interesting, I would say, Shi’ite group, Adawa (ph), which is a clandestine organization inside of the country and certainly is more lethal than SCIRI. They are potentially certainly more troublesome. I don’t know whether politically they will have a greater throw weight, but they are certainly more troublesome because they can hide. They have been hiding from Saddam Hussein’s regime for a very, very long time. So their potential, certainly, if they wish to cause mischief, is fairly enormous.

Now, on the issue of mischief, I would just mention Iran. Now, there are many who believe that the Iranians–certainly on the right side of the sort of political equation in this country tend to believe that the Iranians are going to cause a lot of mischief. I don’t know about that. I actually think the most important thing that’s going to drive the Iranians, it certainly is not going to be loyalty to someone like Al-Hakim. I think that the Iranians will abandon him and SCIRI at a moment’s notice if they think it’s appropriate to do so. What’s going to drive the Iranians most, and it may actually drive them to an extent inside of Iraqi politics to good behavior, is that the Iranians will want to protect at all costs their nuclear program. And that is the thing that I think unifies the clergy. There are very few things in Iran that actually unify them, that they can all agree on. And the one thing they can all agree on is they like the bomb.

And it was, in fact, the first Gulf War that propelled, or, I should say, significantly seriously accelerated the Iranian nuclear program. This Gulf War will reinforce that belief that it is, in fact, atomic weapons that in the end guarantee your survival and guarantee that the United States will not come meddling in your backyard.

So I would expect them actually to be much more serious, and that’s one reason why–I mean, Iranians will do several different things at once. They are, for example, aiding, helping to some extent Ahmad Chalabi and the INC. That is perfectly reasonable for them to do so. They want to have as many different irons in the fire as they possibly can, and I would expect them to be very cautious in the beginning. That’s not to say that they couldn’t change their minds. That’s not to say that they couldn’t try to activate certain units inside of the country. But, again, the one thing that I think you can–the Iranians probably, because they look upon the Iraqis as sort of much lower on the evolutionary ladder, will probably, you know, look at them for a while and determine if, in fact, how much effort they want to invest in them.

I don’t think, for example, that the Iranians are going to exert a great deal of their capital to ensure that one particular Shi’ite player inside of Iraq becomes dominant. I really don’t. I think they’re going to look at the long term here, and, again, they’re going to keep their eye on the nuclear weaponry.

Now, going back to Iraq and the Shi’a, I think that it’s going to take a little bit of time for the Shi’a to coalesce. I would expect them to coalesce as a group. Now, I don’t think that’s necessarily good for the long term in Iraq, and that for our purposes and I think for the Iraqi people’s purposes, it would be better if some type of a political structure develops in that country–it will take time–where certain ethnic and religious loyalties are not predominant. But I think we would be fooling ourselves to believe that initially that is going to happen fairly quickly, and that if the United States is wise, it will do what it can to ensure that those individuals, who will have a democratic majority, in fact, have the gates open to them, that we do not play the game that other people have played in the past, and that is, trying to essentially play to the minority. We should play to the majority. I don’t think that’s terribly hard, and I think we actually will have to do so.

And I would close by simply saying that the preeminent reason why one should have some hope and one shouldn’t sort of laugh and scoff at the idea that democracy inside of Iraq is possible is for the simple fact it makes sense for the Shi’a. Nothing else really makes that much sense. You will not have a restructuring of an Iraqi Sunni officer corps. It just simply won’t happen. The Shi’ites will not allow it. And you will take time–for example, you could maybe dream up a scenario where the Iraqi Shi’a could become militarily predominant in that country, but it will take time. They don’t have that ethos in the officer corps. It simply doesn’t exist. That type of structure, that type of potential views will take, I suggest to you, a few years to form.

In the meantime, there is that window, that opportunity, and I think the Shi’a will be, first and foremost, advocates of that opportunity to create some type of a more liberal, open political system where they can finally have, as they see it–and I think they’re right–their just rewards and deserts.

That’s it.

MS. PLETKA: We’re going to move from toadstools to the United Nations Security Council. Ambassador Kirkpatrick?

AMBASSADOR KIRKPATRICK: Some other options concerning both the use of force and the use of the Security Council. The most important decision that the U.S. Government made, in my judgment, in approaching the question of policy on Iraq was the decision to take the issue to the Security Council, because that’s a decision from which it is somewhat difficult to step back once made. It reminds me in some ways of throwing a ball into play in a basketball game. You know, once you throw the ball into play, it’s difficult to get it back. It’s difficult to stop the play. You have to drive it through to its end.

And what we’ve been doing since our President made the decision to take the issue to the Security Council–which was a decision he need not have made, by the way. There was no particular pressure on him to make that decision. But having made the decision, we’ve spent a very great deal of time already, and thought, on trying to make a case in the Security Council.

Now, I would like to say about this phase of this issue first that this war and this decision to go to the Security Council is quite different than the first Gulf War. There was quite a lot of discussion about whether or not to take the issue to the Security Council in the first Gulf War. When the Iraqis invaded Kuwait, the Kuwaitis, of course, immediately took the issue to the Security Council, simply the issue of Iraq’s invasion, and appealed under Article 51. They notified the Security Council that they were invoking Article 51, which asserts, of course, that all states have the unalienable right to self-defense, to defend themselves and to seek the assistance of others in defending themselves in case of an attack on them.

That decision was made by the Kuwaitis. But then when the United States, and discussion with its allies, made a decision to act to assist the Kuwaitis, there was a big debate in the U.S. Government about whether or not to take that issue to the Security Council.

Now, at that time the Security Council had already unanimously condemned Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, and the Security Council–and the first President George Bush had said this was an intolerable act on the part of Iraq. Now the question was whether before the United States and any other countries took military action to assist Kuwait, we should get the permission of the Security Council.

Margaret Thatcher, who happened to be in the United States at that time, took the view that it was undesirable to take the issue to the Security Council because the United States was, after all, a constitutional democracy which had already made its decision about what it wanted to do, respecting its own constitutional provisions, and the Security Council had already acted, respecting its own constitutional requirements in authorizing the Iraqis–I’m sorry, in authorizing the Kuwaitis to seek assistance from other countries, that there was simply no necessity and no reason for the United States to go back to the Security Council to seek a specific authorization for the use of force to assist the Kuwaitis, and that it was a bad precedent because it created the impression that it was necessary, regardless of the circumstances, for a country to secure the authorization of the Security Council before it resorted to the use of force.

Jim Baker, then Secretary of State, you will recall, took the view that it was desirable to go to the Security Council; if not necessary, certainly desirable; and that it would give a kind of additional patina of legitimacy, and that it would make our allies more comfortable, particularly our allies in the region more comfortable. And Margaret Thatcher suggested this was sacrificing constitutional requirements to comfort of unnamed allies.

But, in any case, President George Herbert Walker Bush made the decision to take the issue to the Security Council, and so there was, in fact, a resolution which did specifically authorize the United States and others, acting under Article 51 and at the request of Kuwait, to use force to drive Iraq out of Kuwait. And we acted on that basis, and we–by the way, we acted on that basis after Secretary of State Jim Baker had spent several months traveling around the area and Europe seeking allies and securing them. Three months, actually.

You can say, well, it’s very desirable to have all those allies. During the time that he was seeking allies, the Iraqis were killing the Kuwaitis. You may recall there was a lot of murdering and raping and pillaging and burning of oil fields and so forth, destruction of the country. But it happened, anyway, and it was a thoroughly authorized action. But it was an action authorized on the basis of quite different circumstances.

Now, it’s also true that this situation, as it is not like the first Gulf War, it is also not like the Balkans. I agree entirely with what’s already been said by Mr. Donnelly about this. The Balkans, military participation in the Balkans was on the basis of a decision by the Security Council, taken initially on its own initiative, actually, to try to act to bring the violent fighting in the beginning between Serbia and everybody else, really, to an end. And then there was a request on the part of Serbia to send peacekeeping forces. No one proposes peacekeeping forces to control the Iraqis, I might say. They would be about as useful controlling the Iraqis as they were controlling the Serbs.

The fighting in the Balkans, which has been long in its duration and intermittently still erupts, actually, was, however, carried out under peacekeeping rules of procedure. The United States never participated in that peacekeeping force. UNPROFOR was the name, U-N-P-R-O-F-O-R, the United Nations force for the Balkans, to bring peace to the Balkans. The United States never participated in it because the United States had just had a very traumatic and terrible experience in Somalia, in which some 19 Americans were killed, you will recall, and 78 or so wounded in Somalia in a peacekeeping operation. And our new President, President Clinton, was unwilling to put Americans under UN control in the Balkans.

The United States participated in the Balkans eventually through NATO and under NATO commands rather than through UNPROFOR and under UN command. And the U.S. decision to participate was strictly an American decision, although it was made with full approval and indeed welcomed by the Security Council.

Where does that all leave us today? It leaves us no place very clear. But we also know that this situation is not like Kosovo. Kosovo is a good example of an instance when the United States and selected allies used a great deal of force without ever seeking authorization from the Security Council. That was the most recent, by the way, example of the U.S. using force in the world, when President Clinton, again, made the decision to use force in Kosovo to stop the slaughter of the Kosovar Albanians, Kosovar citizens. The slaughter was proceeding in a very dramatic and dreadful way.

Why did they make that decision? Because they knew the Russians would veto a resolution which authorized the use of force in Kosovo, so they simply went in without ever seeking a resolution authorizing use of force.

That’s one thing that our President might have done on this occasion had he–it would have been more economical in terms of time and anxiety, probably, if he had simply decided to use force without seeking authorization. Once you seek authorization, it’s a little more sticky because then maybe you don’t get it. If you seek it and don’t get it, then it looks as if you are acting against world opinion; whereas, if you don’t seek authorization, it looks as if perhaps you’re not adequately respectful of world opinion but that you are not flouting it.

In any case, the President made the decision to seek authorization from the Security Council early. I felt myself from almost the beginning that it was going to be a very difficult, sticky problem for the United States to secure authorization from the Security Council. Everything depends on the–well, not everything, but a very great deal–and in a situation–in this situation, everything depends on the composition of the Security Council. And if you look at the membership in the Security Council, you immediately sort of know that we’re going to have difficulties. We’re going to have difficulties with the French really mobilized against us. We wouldn’t have any problems at all if the French weren’t mobilized against us. But the French are mobilized against us, and once you know the French are mobilized against you, against us, then we can anticipate problems, perfectly clearly.

One of my great revelations when I was at the UN was when I realized that it was a great disadvantage not to have been a colonial power, and then it was a great advantage to have been a colonial power. I might just say the first social event I was invited to when I arrived in the United Nations many years ago was–and it had sort of strange guests, group of guests present. And I looked around the room and I looked around the room, and finally I asked the host before I left about the principle on which he had made up his guest list. And he smiled. I said, Let me guess. It was that every person in the room represented a country which had at some time been a British colony. It was a big party. There were a lot of people present.

That was just my first sort of realization about the importance of having been a colonial power. The British, the French, even the Dutch, you know, all manner of countries who had been colonial powers managed at the UN to maintain particularly close relations with their former colonies. And those particularly close relations are very helpful, often, when you’re trying to put together coalitions. And if you never had colonies, then you don’t have that advantage.

Now, if you were the Soviet Union, they were sort of masters at UN politics, and they knew how to put together coalitions. One of the principles that they put together their politics, they didn’t have a lot of trouble persuading their satellites to vote with them, frankly. They always voted with them, 100 percent of the time. They’re very good at politics. The French are very good at politics. The British are very good at politics. The U.S. is not very good at UN politics. We are sort of never very good at UN politics.

It’s not entirely clear why. It has something to do with never having been a colonial power. That would have helped. It has something to do with the fact that we have a long history of simply acting more or less unilaterally. When we have a goal in foreign affairs, we tend to sort of try to put together our own coalition and seek it. That’s just our–that’s our style of acting in foreign affairs. It’s not a good style for playing and becoming skilled at the kind of coalition politics that the UN specializes in.

I think it’s unlikely that we’re going to get the nine votes. Usually, resolutions fail on the basis of failing to get nine votes rather than on the basis of the veto. A failure is a failure. If you don’t have nine votes, then nobody has to veto your resolution. The Soviets were so skilled at UN politics that they almost never had to veto. We, on the other hand, vetoed rather more often during the Cold War. The Soviet Ambassador more than once called me “Madam Nyet,” which was–

[Laughter.]

AMBASSADOR KIRKPATRICK: Because I was doing my duty.

If you look at the resolution the U.S. and Britain are submitting now, you will note that it does not call for action. This is very important. It calls for remaining seized of the issue. That simply is the terminology for kicking the ball down the field, so to speak. You remain seized of the issue, you take no decision about whether to act or not. You just agree to remain seized of it.

What the U.K.-U.S. resolution does also do, however, is provide–it reaffirms every aspect of Resolution 1441 so that it makes it very, very clear, pins down the failure of Iraq to honor and comply with Resolution 1441 and suggests they remain seized of it. I would also suggest–it also says that Iraq is in noncompliance, but it does not advocate action on that except to remain seized.

The French memorandum, which I think is the most pedantic piece of literature I have seen in the UN ever, the so-called memorandum opposing U.S.-Iraq policy, it wasn’t even a non-paper. It’s a memorandum and it instructs the members of the Security Council of the French view of the inadequacy of the American, British analysis of the problem. And, you know, in other words, they give us a C, basically, a C-minus for our efforts. And it also does not advocate any action. It advocates kicking the ball down the field, basically. It says that the Security Council will remain seized–it doesn’t use that word, but that’s what it says–remain seized of the issue and the inspectors will continue earnestly the pursuit of the inspections, and they will do it even more carefully and everyone will await their findings with enthusiasm.

I don’t think there’s going to be–there’s not going to be a vote in the Security Council. I think the next meeting of the Security Council–I don’t even know whether there will be a next meeting of the Security Council, but there may be a next meeting of the Security Council which everybody decides to remain seized and that the inspectors should continue their work. That’s probably not a bad outcome.

MS. PLETKA: Thank you.

Gary, this is probably the first time you’ve ever cursed having the letter M as the first letter of your last name, but thank you for your patience.

MR. MILHOLLIN: Thank you, Dani.

I’m pleased to be a guest here. I run a small think tank in town called the Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control, and I’m a former academic. So I can’t resist the temptation to refer you to further reading, and to make a non-commercial, non-ideological, non-partisan announcement. We do run the largest website on Iraq. It’s called iraqwatch.org, and it has all sorts of wonderful things in it, which, at my age, I can no longer remember having written. But I recommend it to you very strongly.

We conducted a couple of roundtables on Iraq last summer. One was devoted to inspections. We had five former inspectors plus the CIA person who was the point person for the CIA with respect to the Iraqi inspections. And we also had a roundtable on how the war would be fought. We had the commander of the 101st Airborne in the first Gulf War, the commander of the Air Force, and also the commander of most of the Marines. And we’ve written a number of things that have spun out from those roundtables.

I learned a tremendous amount in the roundtables. I’ll start with the one on inspections. Our project has written, I think, three op-eds on inspections in which we pointed out that inspections are not really designed to achieve disarmament. They’re designed to verify that disarmament has happened. And I think the events that have occurred since we had our roundtable and since we’ve written on the subject bear out the truth of that statement. As long as the country being inspected is not cooperating, there is, I think, a very small chance that inspections can achieve disarmament.

The present inspections, I would say, are having the effect of delaying disarmament. If you consider that, for example, there are by export records some 30,000 munitions in Iraq of the kind of which 18 have been discovered, if you discover 18 of these a month, it takes a long time to get 30,000.

Also, if you discover a little bit of chemical or biological agent and you know there are secret sites, and you know that there is capability of production, and you know that there has been past success in production, maybe even weaponization, you have to assume that while you’re inspecting, they could be making a lot more than you’re finding. And so if the effect of inspections is to delay disarmament, to string it out, it’s really–even if you look at the quantities of things produced, it’s probably a losing game.

It’s been suggested that Mr. Blix, when he arrived in Iraq, might have considered just setting up a little booth somewhere and inviting the Iraqis to bring everything over. And if it didn’t arrive in a certain period of time, he would just close his booth and go back to New York, or wherever, and announce that the Iraqis had decided not to disarm.

I think that would have been quite a respectable and responsible point of view to take, at least as effective as the point of view that was taken, which is that the inspection process should go to sites that are already known and look for things that are already listed in the files to make sure those things are still there. That’s okay. There’s nothing wrong with that. But it doesn’t get you to disarmament.

Now, we published this opinion months and months ago–actually, last fall, and, well, I’ll try to be a modest academic, but it is true that things have gone pretty much according to the schedule that was laid out for us by the former inspectors at our roundtable.

The last act, of course, has not occurred yet, the last act they predicted, and that act is that Saddam finally starts bringing things to the booth right at the last minute. When the troops really look like they’re coming across the border, our inspectors expected the Iraqis to show up with more. And that would be a trigger for their lawyers in the United Nations, the French and the Russians, to immediately ask for a new trial, stay the proceedings, emergency appeals. I think that is awaiting us, probably. At least that’s what was predicted by them last summer, last fall. So I think we’re going to see one more little chapter of the drama of inspections before it ends.

The second thing I’d like to talk about is what we’re likely to–Dani asked me to talk about is what we’re likely to find in Iraq after the war. The short answer to that is we’re going to find our own stuff. We’re going to find the products that the West supplied. These products are–I just can’t resist this–listed in great detail in iraqwatch.org.

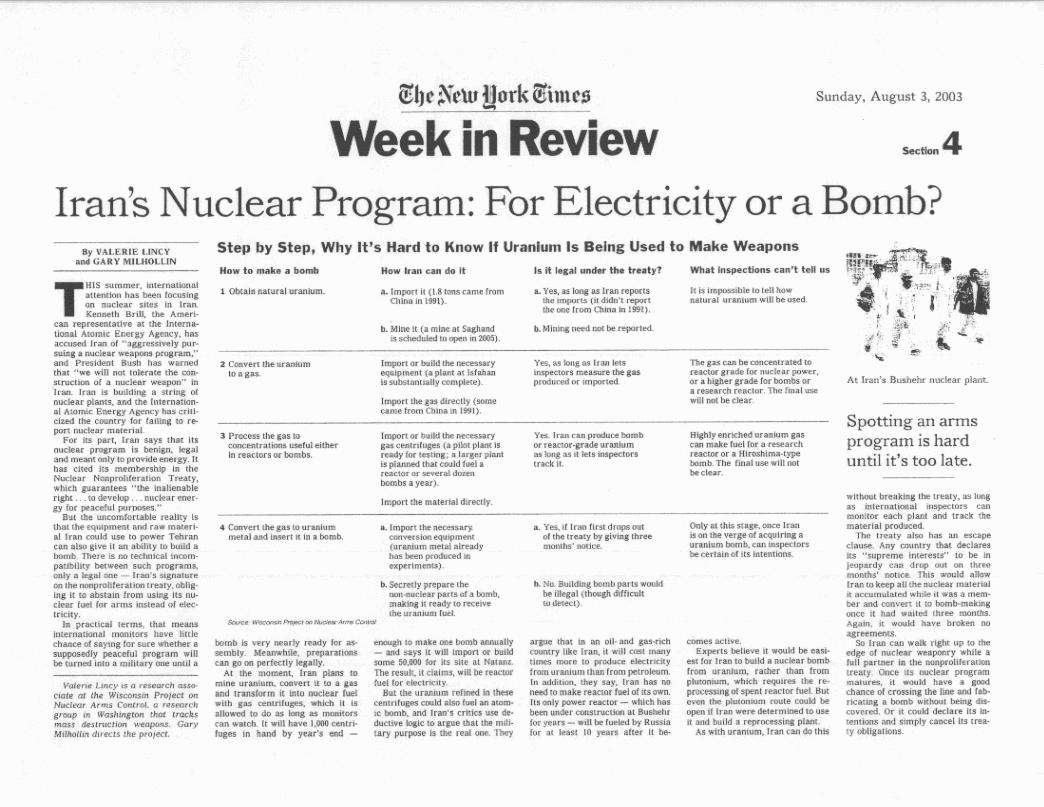

We did a large graphic for the New York Times Week in Review, a pie chart showing who supplied what to Iraq. These are things that we’re still looking for, by the way. These were things that were supplied just before–for the most part, just before the Gulf War.

One of the most dangerous and irresponsible exports, in my opinion–here we go, we’re getting personal now–was made by a company that I noticed on the elevator on the way up this morning, Unisys, two or three floors — [tape ends].

[Laughter.]

MR. MILHOLLIN: Does Unisys contribute?

Unisys sold the Iraqi Ministry of the Interior about an $8 or $9 million computer system especially configured for tracking individuals. This was in the late ’80s. That was a lot of money back in those days for a computer system. Computers didn’t cost very much in the late ’80s. For an $8 million system configured to track individuals, that’s a lot of tracking power.

I think it’s pretty clear that that computer has helped Saddam stay in power if it’s still working, and it certainly helped him hang on during the early ’90s. And we have a literal mountain of information about who supplied the WMD programs in Iraq. Mostly it was the Germans.

In our pie chart–it’s a great pie chart. I recommend that you look it up at iraqwatch.org.

[Laughter.]

MR. MILHOLLIN: It shows the Germans supplied 50 percent of all of the WMD-related things that the Iraqis imported and that the rest of the world divided the remainder. The Swiss came in second. The Swiss have an unreasonably good reputation in the world. Actually, if you look at their exports, they are not a clean country when it comes to WMD exports. At least they haven’t been. They came in second. The United States was not innocent. Saddam was a good shopper. He bought his machine tools from the Germans and the Swiss. He bought the electronics from us.

U.S. electronics went into almost every major weapons site in Iraq. It went to the Iraqi air force, went to Iraqi nuclear sites, went to Iraqi missile sites. And in several cases that I know of, the destination and use of those things was revealed during the export control process, and most of this, the lion’s share of it, was approved by the Commerce Department, and approved by other countries. Most of what Saddam imported was not smuggled. It was legal. It was approved. I’m talking about turnkey poison gas plants, as someone said, for two-legged flies. These were imported from Germany, turnkey. At the same time Germany was selling poison gas plants to Libya, it was selling the same thing to Iraq. This was in the late ’80s.

Both of the poison gas plants in Libya need process control computers to determine how these–to run the chemical operations. The first process control computer–sorry, Dani. This is one of my favorite subjects here.

[Inaudible comments.]

MR. MILHOLLIN: One of the–the first process control computer–this was at Rapta (ph), the poison gas plant–was made by Siemens. Well, that created somewhat of a stir. Siemens has sent delegations to our office on three different occasions asking how they can “get off our list.” We put Siemens in the New York Times frequently. The answer is you can stop selling bad things.

The second poison gas plant that Mr. Qaddafi built was under a mountain called Tarhuna (ph). It, too, needed a process control computer.

Now, where do you suppose the process control computer for the second poison gas plant came from? It came from Siemens.

The point I’m making here is that this problem in Iraq that we’re going to solve with U.S. troops and U.S. blood and U.S. treasure is an imported problem. The WMD program is imported lock, stock, and barrel. There’s no indigenous capability in that country. And the same is true of Iran. It’s imported, and it’s imported–Saddam imported it from us in the ’80s.

Now, we have done better through public humiliation, generated mostly by our little operation. The West has been a lot more careful since the Gulf War. The procurement efforts by the Iraqis have been turned east to Eastern Europe. That’s now the weak place–Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Belarus. Those are the targets.

In iraqwatch.org, you can also find articles about that. But you should be clear that this is a global problem that Iraq is only one part of it, and Iran is another part of it. And it’s not being solved. And so even if we go into Iraq and find all this, which we will, there’s the question in my mind whether it will be public; that is, it’s going to be an interesting thing. I hope you all keep this in mind. Watch and see what happens. There will no longer be any just reason for shielding the companies that supplied Saddam. They’re now being shielded from official disclosure by the argument that, well, investigations are still going on and we need their cooperation. After the war, that argument won’t be present. I’ll bet you that it will still be covered up, that it will have to be extracted by journalists and people like me so that we can learn a lesson or two from what actually was sold to Iraq.

Well, have I exhausted my time here?

We did one other roundtable that I mentioned on how the war will be fought. I don’t want to encroach on others’ territory, but our general said that it would be a Panama-like operation in which we would come at the Iraqis from all sides at the same time, there would not be a prolonged preliminary bombing campaign, and that we would try to paralyze the Iraqis and split up their forces and demoralize them, just as we did in Panama, but on a much larger scale, and that about 250,000 to 300,000 troops would be used.

It seems to me like that was a pretty good prediction. That was, as I said, made last summer. So you can read all about the historical antecedents of today’s news stories if you’d look at–what was the name of it again? I’ve forgotten.

I’d like to close by saying that when we finish up in Iraq, it’s going to be very important to make sure that we have everything. And it’s possible that things are going to start leaving Iraq before the war or during the war, and there may be a need to track where they went in the world. That we’re not quite ready for, but I think it may come about.

Thank you, Dani. I’ll stop there.

MS. PLETKA: Gary, I’ve been a little bit embarrassed that I wasn’t more fulsome in your introduction, but luckily we all know where it is. And, by the way, just an impartial endorsement: It is a fantastic website, incredibly useful, and, of course, now everybody understands where we’re deriving all our information. So much for free riding, I guess.

We’re going to open up the floor to questions. I do want to make sure that you, Gary, at some point take the opportunity, hopefully with a question from the audience, to explain the concept of dual use that I think escapes many people. Because the reason–and when I used to be on Capitol Hill, we fought this fight many times. The reason that Iraq and Libya and Iran and others can buy these things with licenses, not just from the United States but from European countries and from others, is the great concept of dual use. And I think one of the other things that you didn’t mention that we will find when we do go into Iraq and get rid of Saddam is that a lot of the dual-use items that he’s been using since the Gulf War, when the United States stopped licensing things, were bought through the oil for food program with the sign-off of the United Nations.

MR. MILHOLLIN: That’s true.

MS. PLETKA: So that’s another important factor to bring in.

So, in any case, with that last comment I’m going to open the floor to questions, and if everybody would confine their question to a question, not a speech, please, and if you would wait for the microphone and identify yourself. Thank you.

The gentleman over here has his hand up.

MR. LOGUE: I’m Jim Logue (ph) from Interpress Service. I’d like to ask Mr. Gerecht, or anybody else on the panel who would care to take on the question, I’d like you to compare the kinds of uncertainties that surround internal Iraqi politics and the dynamics that might be set off by an invasion/occupation with the situation in Lebanon in ’82 through ’85. Many of the same voices who have suggested that this invasion and occupation could kind of transform the whole region said very much the same thing when Israel was about to throw the PLO out of Lebanon, which was kind of a regime change. And indeed they were welcomed fulsomely by the Shi’a population in particular that had been oppressed by the PLO in the south. But obviously, subsequent events suggested that kind of falling out, and it just never happened the way it was supposed to happen.

I would like you to address kind of the–to what extent that is a cautionary tale for what we’re about to do in Iraq, which is a much larger country, with many more borders.

MR. GERECHT: Well, I’m not sure historically there’s actually that much in common between Iraq and the minorities in Iraq or the various component parts of Iraq and the component parts of Lebanon. I would say, to make some type of parallel, that it certainly behooves us to take into consideration, great consideration, the aspirations of the Shi’a in Iraq. The Israelis undoubtedly made a mistake in Lebanon. They sided with a minority and ignored, if not on occasion brutally dismissed, the aspirations of the Lebanese Shi’a. I think that that would be a serious mistake. I don’t think the United States will make that mistake in Iraq. And I don’t know if I would take any parallel beyond that other than to say that it would be truly a tragedy if the United States listened to those voices elsewhere in the Arab world that want us to essentially try to perpetuate the minority domination of the Sunni.

I just don’t think that can happen. I think once the lid is blown off and when the Ba’ath go down that the Shi’a will inevitably, ineluctably become the dominant voice in that country, as they should be. And I think the United States obviously will have to deal with that, and I hope that it deals with it responsibly.

MR. MORROW: Steve Morrow, (?) . Actually, two quick questions. First for Dr. Milhollin, any comments on the reports over the last few weeks that chemical weapons from Iraq have shown up with the Hizbollah in southern Lebanon?

And the second question is to Ambassador Kirkpatrick. You mentioned the case study to Kosovo and how in that situation authorization was received by the regional multilateral of NATO and, therefore, not seeking at the UN. In this particular case, the same members that are mobilized against the U.S. at the UN are mobilized against the U.S. and Turkey and NATO. Do you feel that there’s any long-term damage to the NATO alliance?

MR. MILHOLLIN: I don’t have any specific knowledge about the question you pose concerning the migration of chemical weapons. One thing I didn’t mention that we might find in Iraq–I hate to bring this up, but there were a lot of rumors and a certain amount of evidence concerning human experimentation, experiments on humans with chemical and biological agents. I don’t know whether we’re going to find that or not. If we do it would be, I think, well, rather spectacular. But there is that possibility.

But to answer your question, I don’t know.

MR. : [inaudible – off microphone].

AMBASSADOR KIRKPATRICK: I think there are various factors that today threaten the NATO alliance, obviously threaten the cohesiveness and the capacity to act of the NATO alliance. But I don’t think any of them threaten it definitively, in fact. And I take the case of Turkey two weeks ago when France sought to block NATO’s assistance to Turkey. The United States took the initiative in moving the issue to a NATO body in which France was not present, since France withdrew from NATO, from the governing portions of NATO, General de Gaulle, President de Gaulle, in 1966, I think, and has rejoined the military portions but not the governing portions. And so it is not present.

I think that the more you expand the membership of an organization such as NATO and the less clear its function is, as compared today to the Cold War, let’s say, the more possibilities there are for dissension and disagreement within the organization. But I don’t see any imminent ones.

MS. PLETKA: I’m going to answer your first question about the transfer of chemical weapons. I don’t think anybody knows for sure, but one of the things that concerns the United States and others about Iran throughout the 1990s was the fact that they began to play a coordinating role among terrorist groups, and they ran what was called the Jerusalem Committee, and they would bring all the terrorist groups. Few people have paid attention to the fact that Iraq has now also taken that role and that there have been a number of significant meetings in Baghdad of radical terrorist organizations, not just al Qaeda but others, including Hizbollah, the various Palestinian groups, where they’ve come to Baghdad, have meetings, including during this year, where they’ve talked about it. Take that in conjunction with the fairly recent announcement by the spiritual leader of Hizbollah, Sheikh (?) , that, in fact, the enemy is no longer Israel or just Israel but that, in fact, Israel is only a soldier for the greater enemy, which is the United States.

It’s the first time he ever said that. Did they hear that in Baghdad? I wonder.

Anyway, let’s turn to somebody else. The gentleman right here.

MR. : Thank you. My name is Tadashi (?) , Johns Hopkins University. I have a question to Ambassador Kirkpatrick with respect to the French-German memorandum. When I looked through this memorandum, they are trying to set forth a detailed mechanism of intensified inspectors by referring to the two previous Security Council resolutions. You said that it’s just a memorandum, not a resolution.

My first question is: What is your judgment, what is the French-German real intentions to set for this mechanism?

Secondly, what happens next if the U.S.-U.K. resolution cannot get the nine votes? What happens? What’s the action from the French side?

AMBASSADOR KIRKPATRICK: I think that to answer your second question, which is easier to answer first, if the United States–if the resolution supported by the United States and the U.K. and Spain and Bulgaria does not pass–if it is–I don’t think it will be submitted. Well, if it is–it will be submitted, all right. Maybe it will be, maybe it won’t. We don’t know. But probably it will be submitted, and it will pass, and it will simply direct the Security Council to remain seized of the issue. In that resolution there is no confrontation. There is no up or down vote, no yes or no, no go to war, don’t go to war proposition.

So I think on the basis of what is now before the Security Council we will not see any decision by the United States to act or not to act. We will simply–I think that the opposition of–determined opposition and leadership of the French, which may perhaps lead to the inability of the United States to get nine votes, that the result will be simply that if the United States acts against Iraq with its allies, it will act outside, without any kind of Security Council authorization, just as it did in Kosovo and as it has done–as virtually every country that has used force against anybody has done in recent years. The Soviets, of course, never went to the Security Council for authorization of the use of force.

You had a second question?

MR. : [inaudible].

AMBASSADOR KIRKPATRICK: You know, I think there are two intentions, probably. I’ve been a student of French politics for almost all my adult life, let me say, and so I’m particularly interested in this whole development. And I think that France has a very serious desire to establish itself and remain established as the leader of the European Union. That is, I think, the–which is to say then of the UN, if you can lead the–I’m sorry. If you can lead the EU, then you can lead the UN. Think about the fact that the EU already has 16 votes to the United States’ one. This is what Joseph Stalin proposed at the time the UN was established, and Franklin Roosevelt rejected it and proposed instead that then the United States would have 48 votes and each state would have a vote.

Well, they settled that with that silly compromise where Ukraine and Belarus had votes in the Security Council, along with Russia.

I think that’s France’s principal concern, and its principal concern is that the United States not be more influential than France is. I think that’s the driving concern, really.

I believe that as far as Germany is concerned, which I feel I know less well than I know France, it’s a continuation of Prime Minister Schroeder’s election tactics, I believe. I think it’s a popular position at home, and I think he’s somewhat interested, perhaps, too, in maintaining a Franco-German kind of entente which they can exercise principal power inside the EU and outside the EU in the UN.

MR. DONNELLY: Dani, could I just give a footnote to that?

MS. PLETKA: Yes, absolutely, Tom.

MR. DONNELLY: Just to sort of make a point that I’ve made before, and that is that it’s a mistake to contemplate the diplomatic maneuvering absent from the military deployment. The whole question of the utility of diplomacy from an American point of view has to be regarded in light of what military option the United States has. Very shortly all the military options become attractive, much more attractive than they have been. So using the period of deployment as an opportunity to come to some diplomatic resolution of how to deal with the Iraq problem is quite a different proposition than pursuing diplomacy after the deployment is complete and the military option is as attractive as it’s ever going to be and only degrades as time goes on.

So these are two curves that are almost about to pass, and the way one interacts with the other, if you don’t remember that, you miss half the picture.

MS. PLETKA: One of the most instructive things about the French support of enhanced inspection is that it was the Government of France in November and October and September that most strongly opposed the idea of stronger inspections, more inspectors, enforced inspections. And, in fact, people who had access to the various iterations of the Security Council Resolution 1441 before it passed will see that the French did nothing but excise any attempt to strengthen the inspection regime. So one has to ask oneself why they suddenly arrived at that point now and where they’ll be six months from now.

Next question–

AMBASSADOR KIRKPATRICK: May I add just a word?

MS. PLETKA: Yes, please.

AMBASSADOR KIRKPATRICK: I would just like to remind everyone present that when the Israelis destroyed the Osirak reactor, which was near completion, you may recall, they had sought to attack the reactor at a time that there would be no people present so there would be no casualties. There was, in fact, a casualty. There was one person in the building on a Sunday afternoon, working hard, and it was a Frenchman who was working on assisting the Iraqis with the completion of the Osirak reactor. Just bear that in mind.

MR. : [inaudible].

MR. MILHOLLIN: One more footnote. Why not? When the reactor was supplied, it used high enriched uranium fuel, and there was a question how much fuel the Iraqis would get because the fuel was enriched to a point where it was directly usable as nuclear weapon fuel. It was 93 percent. You can do the chemistry in your basement. It’s not radioactive. You can just separate–you can do basic chemistry with fuel rods, and you get bomb material.

Well, the French wanted to supply three full core loads, which would have been a small nuclear arsenal. We talked them–and Jacques Chirac was the point person for the French in this reactor deal. Some people called it the O’Chirac reactor. It was modeled after a small reactor in France. Same thing, same reactor. The Indians also have a small reactor which is a copy of a French reactor.

But think of what would have happened had we not convinced the French not to supply three full core loads. When the Gulf War began, the Iraqis immediately diverted the fresh fuel, but it wasn’t enough for a bomb. One core load was not enough. Three core loads would have been plenty.

We also required the Iraqis to lightly irradiate the one core load they got, that is, they zapped it a little bit in the critical assembly that they had, which made it harder to deal with and made it harder to divert the material to bomb–to use in bombs. But that was because of U.S. diplomacy, and it was over the opposition of the French, who basically wanted to hand the Iraqis enough fresh, directly usable material for two or three bombs with this reactor.

That’s my little footnote.

MS. PLETKA: I’m going to give for iraqwatch.org a picture of Saddam Hussein and Jacques Chirac inside a nuclear reactor.

Wait for the mike, please.

MR. DREYFUSS: I’m Bob Dreyfuss (ph) from the American Prospect. I wonder if Dani and Reuel could talk a little bit about the recent meeting of the Iraqi opposition groups in northern Iraq and some of the sort of politics swirling around that and what (?) Azad (ph) has been doing back and forth and so forth, and sort of what all that has to do with war preparations. You know, how do we get from what they’re doing to a post-war situation? And perhaps, Mr. Donnelly, you could talk a little bit about–if you could something about what the military planners are doing in terms of actually how they would transition to a political administration in Iraq and sort of who is doing what in Washington, if you know.

MS. PLETKA: Do you want to answer first?

MR. DONNELLY: Sure. I’ll be very brief. The immediate military planning is obviously focused on making sure that there isn’t a humanitarian, ecological, or any other catastrophe that is an inadvertent by-product of the campaign itself. So, you know, obviously you will see relief operations following along in the immediate wake of combat operations, because obviously part of our purpose is to begin the reconstruction of Iraq in many dimensions absolutely as soon as possible. And I think you have to take the administration sort of at its word, although there is clearly a debate and division between the various agencies of the government about who and how to accomplish this, but certainly the intent is to try to begin to involve Iraqis is as many aspects of this reconstruction, and especially in political reconstruction, at the earliest date possible.

You know, clearly, as I say, there’s a debate inside the government. There are big divisions between the State Department and the Defense Department. There are internal divisions in the Defense Department between folks in uniform and folks in suits. And, you know, until it actually happens, there’s sort of no way to know for sure how that internal debate–and, again, a lot of it will depend–this will be a huge opportunity. As Reuel said, we don’t know in the Shi’a community who’s going to emerge as a natural leader. That’s the whole point of this exercise, is to sort of recalibrate Iraqi internal politics, and not only in the Shi’a community but, you know, in the other communities in Iraq as well. To say that we know today who is going to emerge as the natural political leaders in Iraq is, you know, probably a long shot at best.

MS. PLETKA: I don’t want to digress too much in talking about the Iraqi opposition, but I think the simple answer is that the Iraqi opposition thinks that Saddam is going to be gone, and they want to start planning for the future, which is all to the good.

I also believe that there has been in the last few weeks a sea change inside the U.S. administration and a growing understanding that America, while it would have been advantageous for us to have been a colonial power, isn’t perhaps going to start now, and that we’re going to need Iraqi partners and that the best place to start finding those partners is among the people who have been fighting Saddam not only from inside Iraq but from outside Iraq for a long time. That’s why we had good American representation in northern Iraq. That’s why the White House welcomed the statement of the Iraqi opposition. And we’ll see in the coming weeks how much we are able to work with them. Hopefully it will be more and more.

We’re going to take one last question. This gentleman here, and then we’re going to have to close up.

MR. : Yes, Chao Chen (?) , (?) correspondent. My question is to Professor Milhollin. I have two things. First is this: Which article you say published in which news media? And secondly is this: Do you have a monetary total of the products each Western country sold to Iraq? If you don’t have, maybe it’s very good to have that total so we can rank among them.

MR. MILHOLLIN: I’m sorry. Can you state your first question again?

MR. : You mentioned that you have an article published. Where?

MR. MILHOLLIN: Oh.

MR. : I’m sure they’re all available at iraqwatch.org.

[Laughter.]

MR. MILHOLLIN: This is not a paid question. You can find our publications in two places: on iraqwatch.org, all one word, and our institutional website, which is called wisconsinproject.org.

The article on who supplied Iraq came from about a 200-page table we did at about the time of the war which had exports and imports from all countries in the world. Our exports to Iraq were in the many billions of dollars. But they were smaller than other countries’. I hope this interests the rest of you to some extent.

The United States and Germany, and other countries that supply dual-use equipment–dual-use equipment is something that can be used for civilian purposes or for military purposes. Example: There is a machine that destroys kidney stones inside the body called a lithotriptor. Siemens sold six lithotriptors to the Iraqis a few years back. Each lithotriptor contains a small electronic high performance switch which is the same switch that is used to detonate nuclear weapons. Saddam wanted to buy about 200 extra switches for spare parts.

MR. : They break a lot.

MR. MILHOLLIN: Yeah, they break a lot. It’s unclear how many he got. That’s a dual-use item.

In terms of numbers, actually the French and the Russians supplied conventional military equipment to Iraq which was worth a lot more than the dual-use equipment that countries like Germany and Switzerland and the United States supplied, because a jet costs a lot more than a computer. So in my view, the German exports were even more culpable because they produced a more nefarious result and generated much less income; whereas, the French, they were supplying fighter jets, which couldn’t be used during the first Gulf War because they couldn’t be–I’m sorry. They supplied fighter jets, and when the French wanted to help us during the first Gulf War, we had to keep their jets out of the way because we couldn’t distinguish them from the Iraqi jets. That’s a nice little story.

The French have a history here. The French and the Russians supplied–and the Russians, of course, supplied 819 Scuds, one of which killed our troops in Saudi Arabia, others of which landed in Tel Aviv. These were–the ranges of these Scuds had to be increased to reach their targets. But the Germans sold turbo pumps and other things that allowed the range to be increased.

I’ve often thought it would be a good idea to–well, to just look at the missiles that actually killed our troops, take it apart piece by piece to see where it came from. It would be an interesting exercise. Never had time to do it. It would be an international missile.

But the numbers are in the billions of dollars if you add it up. The numbers don’t necessarily correspond to the importance. Something that doesn’t cost very much can be very important. Like these little switches, they can be very important to a nuclear weapon effort, but they’re not very expensive. So it’s not always a question of dollars.

MS. PLETKA: That is an important reminder to all those countries who accused of trying to interfere with the humanitarian support of Iraq, that when they wanted things like lithotriptors and atropine and chlorine gas, that they may have been using it for just those purposes.

Anyway, with my final two cents, I want to thank everybody, especially Gary for not only waiting until the end to speak but being so fascinating, but all of our guests and scholars and all of you. We’ll be doing this again next week, Tuesday at 9 o’clock. Thank you all very much for coming.