Executive Summary

The indictment of Turkish state-owned Halkbank, unsealed late last year, is the first against a major bank for sanctions violations brought by the United States. The case sheds light on how, from 2012 to 2016, in the midst of negotiations on its nuclear program, Iran relied on this bank to launder money in order to relieve the economic pressure of international sanctions. The four-year legal saga began in 2016 with the arrest and prosecution of Reza Zarrab, an Iranian-Turkish businessman. Zarrab masterminded a scheme to launder billions of dollars of Iranian oil proceeds through Halkbank under the guise of gold and food trade. Evidence presented during the 2018 trial and conviction of Zarrab’s co-conspirator Mehmet Hakan Atilla, a Turkish national and former deputy general manager of Halkbank, implicated Turkish President Recep Erdogan. The ongoing case against the bank has been a point of contention in already-fraught U.S.-Turkey relations. Due to a series of appeals and postponements, the case remains in legal limbo. However, in as the United States ramps up its pressure campaign against Iran, and Iran ramps up its nuclear program, the case provides lessons learned for how to prevent Iran from exploiting the international financial system to evade sanctions in support of proliferation.

The indictment of Turkish state-owned Halkbank, unsealed late last year, is the first against a major bank for sanctions violations brought by the United States. The case sheds light on how, from 2012 to 2016, in the midst of negotiations on its nuclear program, Iran relied on this bank to launder money in order to relieve the economic pressure of international sanctions. The four-year legal saga began in 2016 with the arrest and prosecution of Reza Zarrab, an Iranian-Turkish businessman. Zarrab masterminded a scheme to launder billions of dollars of Iranian oil proceeds through Halkbank under the guise of gold and food trade. Evidence presented during the 2018 trial and conviction of Zarrab’s co-conspirator Mehmet Hakan Atilla, a Turkish national and former deputy general manager of Halkbank, implicated Turkish President Recep Erdogan. The ongoing case against the bank has been a point of contention in already-fraught U.S.-Turkey relations. Due to a series of appeals and postponements, the case remains in legal limbo. However, in as the United States ramps up its pressure campaign against Iran, and Iran ramps up its nuclear program, the case provides lessons learned for how to prevent Iran from exploiting the international financial system to evade sanctions in support of proliferation.

Introduction

On October 15, 2019, U.S. prosecutors unsealed an unprecedented six-count indictment against Halkbank, a major Turkish state-owned financial institution, charging the bank with fraud, money laundering, and conspiracy to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). The U.S. Department of Justice decision to prosecute Halkbank is an unusual step. U.S. prosecutors usually seek to settle out of court with banks accused of sanctions violations, through deferred prosecution agreements.

On October 15, 2019, U.S. prosecutors unsealed an unprecedented six-count indictment against Halkbank, a major Turkish state-owned financial institution, charging the bank with fraud, money laundering, and conspiracy to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). The U.S. Department of Justice decision to prosecute Halkbank is an unusual step. U.S. prosecutors usually seek to settle out of court with banks accused of sanctions violations, through deferred prosecution agreements.

The indictment came at a tense time in U.S.-Turkey relations. A week earlier, Turkish troops had entered northeastern Syria to attack the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, a key U.S. ally in the campaign against the Islamic State. The incursion prompted a political backlash in the U.S. Congress. The House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed the Protect Against Conflict by Turkey Act (H.R. 4695), which called for sanctions against entities affiliated with the Turkish government, including Halkbank specifically.[1] Similar bipartisan bills were introduced in the Senate, but were set aside when the administration negotiated a ceasefire agreement.[2]

The case has been dogged by allegations of political interference. Turkey reportedly lobbied the Trump administration to withdraw the charges against Halkbank and Reza Zarrab, an Iranian Turkish businessman who was the architect of the scheme.[3] Testimony from Zarrab during the trial of co-defendant Mehmet Atilla, the former deputy general manager of Halkbank, directly implicated Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and several other senior Turkish government officials.[4] Nonetheless, the facts of the case illustrate how Iran successfully evaded U.S. and international sanctions that were meant to constrain its proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

The operation’s purpose was to allow the Iranian government a means of accessing its oil and gas revenue held overseas. As part of the scheme, Zarrab funneled money from Halkbank accounts held by Iranian entities to accounts of his front companies in Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Then, after laundering the money through illicit gold exports and later falsified food trade, Zarrab ultimately used those funds to make international payments on behalf of Iranian entities that support Iran’s proliferation programs. According to the Department of Justice, the scheme “fueled a dark pool of Iranian government-controlled funds that could be clandestinely sent anywhere in the world.”[5]

The Setup

The money operation was masterminded by Zarrab, who owned a network of exchange houses and front companies in Turkey and the UAE.[6] See the appendix for a list of the entities in Zarrab’s network, including a description of their role in the scheme. In 2011, prior to engaging Halkbank, Zarrab initiated a series of wire transfers on behalf of the MAPNA Group, a construction and power company with ties to Iran’s nuclear and missile proliferation programs,[7] as well as on behalf of a money services subsidiary of Bank Mellat,[8] which has provided banking services in support of Iran’s proliferation programs.[9] Despite some initial success, several attempted financial transfers to companies in China and Hong Kong via intermediary U.S. financial institutions were blocked in the spring of 2011, pursuant to sanctions issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) targeting Iran’s financial sector.[10]

Looking for a larger – and more lucrative – role, Zarrab signed a letter to Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in December 2011 expressing his family’s “readiness for any collaboration in moving currency as well as adjusting the rate of exchange under the direct supervision of the honorable economic agents of the [Iranian] government.”[11] He soon found a vehicle for the grand sanctions evasion scheme he envisioned: Halkbank.

The Gold Scheme

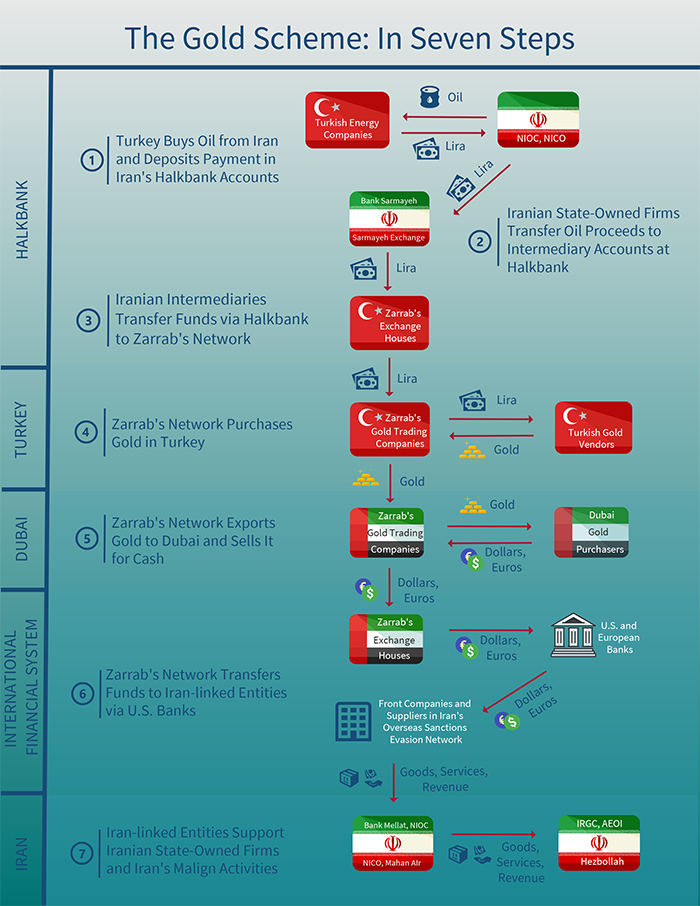

In early 2012, a representative from Sarmayeh Exchange, a money services subsidiary of Bank Sarmayeh, a private bank in Iran, informed Zarrab that the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) and the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) held billions of dollars in accounts at Halkbank. The funds consisted of the proceeds from Iranian oil and gas sales to Turkey.[12] Pursuant to sanctions imposed by the U.S. National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2012, money from these oil escrow accounts could not be transferred back to Iran or used for international financial transfers on behalf of the government of Iran or Iranian banks.[13] In July 2012, Executive Order 13622 further restricted petroleum-related transactions with CBI and NIOC specifically.[14] At the time, however, funds from the accounts could legitimately be used to pay for Turkish exports to private Iranian companies – an exception known as the bilateral trade rule.[15]

In March 2012, Zarrab approached Halkbank general manager Suleyman Aslan with a scheme to channel funds to the Iranian government by exploiting the bilateral trade rule. Finding Aslan at first reluctant to participate, Zarrab secured the support of Turkish Minister of Economic Affairs Mehmet Zafer Çağlayan with over $70 million in bribes.[16] Zarrab later bribed Aslan with $8.5 million.[17] Several other Halkbank officials were also involved in the scheme, including Atilla who headed the department responsible for processing international banking transactions, and his deputy Levent Balkan.[18] Zarrab, Aslan, and Atilla held numerous meetings with officials from high-profile Iranian institutions – primarily CBI, NIOC, and Naftiran Intertrade Company (NICO) – to coordinate the conspiracy.

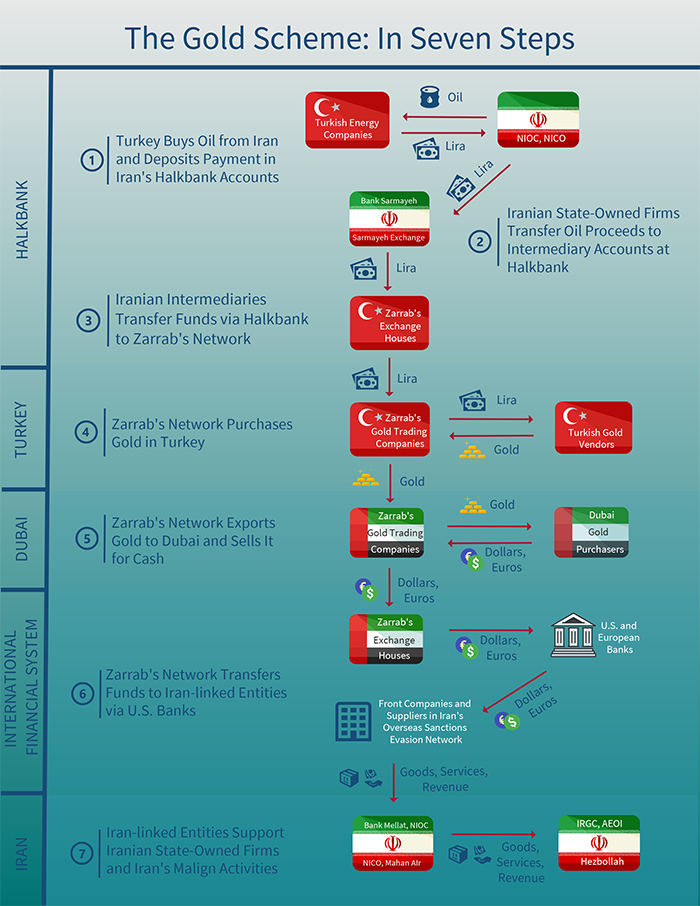

The initial operation involved the laundering of Iranian oil and gas revenue through a gold export network. First, CBI and NIOC would transfer the oil revenue held in their Halkbank accounts (denominated in Turkish lira, so as to avoid the international financial system) to the Halkbank accounts of private Iranian banks, such as Bank Sarmayeh.[19] Those Iranian intermediaries then transferred the money to Halkbank accounts controlled by Zarrab’s network of front companies, thereby concealing the Iranian connection from outside financial institutions.[20]

Zarrab’s front companies used the funds to buy gold on the Turkish market. To further cover his tracks, Zarrab then falsified records to indicate that the gold was subsequently exported to private companies in Iran, as permitted by the bilateral trade rule.[21] In this way, even if the internal Halkbank transfers could be traced back to the Iranian oil accounts, the transaction would still appear to be in compliance with U.S. sanctions (this falsified documentation later underwent several changes as U.S. sanctions evolved).[22]

In reality, Zarrab’s companies exported the gold to Dubai, where they then sold it on the market for cash. This step was critical to Zarrab’s scheme and served two purposes. First, it allowed him to acquire currencies used for international payments, such as the U.S. dollar and the euro. Second, it disguised the money’s Iranian origin. Unlike bank transfers, cash transactions cannot easily be traced.

At this point, the money was ready to be moved in the international financial system. Zarrab deposited the cash proceeds from the gold sales into accounts held by his companies at banks in Dubai. Iranian banks, such as Bank Sarmayeh and Bank Mellat, then gave Zarrab’s companies instructions to transfer the money to various entities in Iran’s sanctions evasion network, composed of front companies and foreign suppliers in several countries including Canada, China, and Turkmenistan.[23] U.S. banks then unwittingly processed several of these dollar transactions through correspondent accounts.[24] As a result, from December 2012 to October 2013 alone, more than $900 million of Iranian oil and gas money transited through U.S. financial institutions to make payments on behalf of Iran.[25]

The gold scheme’s success made it a focal point of Iran’s sanctions evasion efforts worldwide, as Zarrab and Iranian officials attempted to expand and replicate it. In October 2012, for instance, several of the conspirators met to discuss moving Iran’s oil revenue in India to Halkbank so that it could be laundered through the scheme.[26] It is unclear to what extent the India plan succeeded. Zarrab also testified that he operated a version of the gold scheme in China for several months in late 2012, until the operation was shut down by Chinese banks.[27]

The scheme also benefited Turkey by artificially inflating its export statistics, making the Turkish economy appear stronger than it actually was. Recorded gold exports to Iran went up from $55 million in 2011 to $6.5 billion in 2012; gold exports to the United Arab Emirates increased from $280 million to $4.6 billion.[28] Almost all of that increase can be attributed to funds laundered from Halkbank through Zarrab and his companies. Consequently, the scheme, once running, appears to have been encouraged at the highest levels of the Turkish government. In the summer of 2013, Aslan was allegedly instructed in a meeting with then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Çağlayan, and other Turkish government officials to “take care of this job” – namely, to increase Turkey’s gold exports from its previous high of $11 billion in 2012.[29]

Throughout the scheme, Aslan and Atilla made a series of false statements in meetings with U.S. Treasury officials, telling them that Halkbank was not providing Iran with gold or cash revenue from its oil reserve accounts, adding that they had rebuffed an approach from CBI to acquire gold.[30] The U.S. officials nonetheless continued to caution Aslan and Atilla that Halkbank would be a prime target for Iranian sanctions evasion efforts, telling them in February 2013 that they were in a “category unto themselves” due to this heightened exposure.[31]

In July 2013, Halkbank informed Treasury that it had stopped facilitating any gold exports to Iran as of June 10.[32] The scheme nonetheless continued until at least December 2013, with over nine tons of gold shipped after Halkbank’s July statement to OFAC.[33]

The Food Scheme

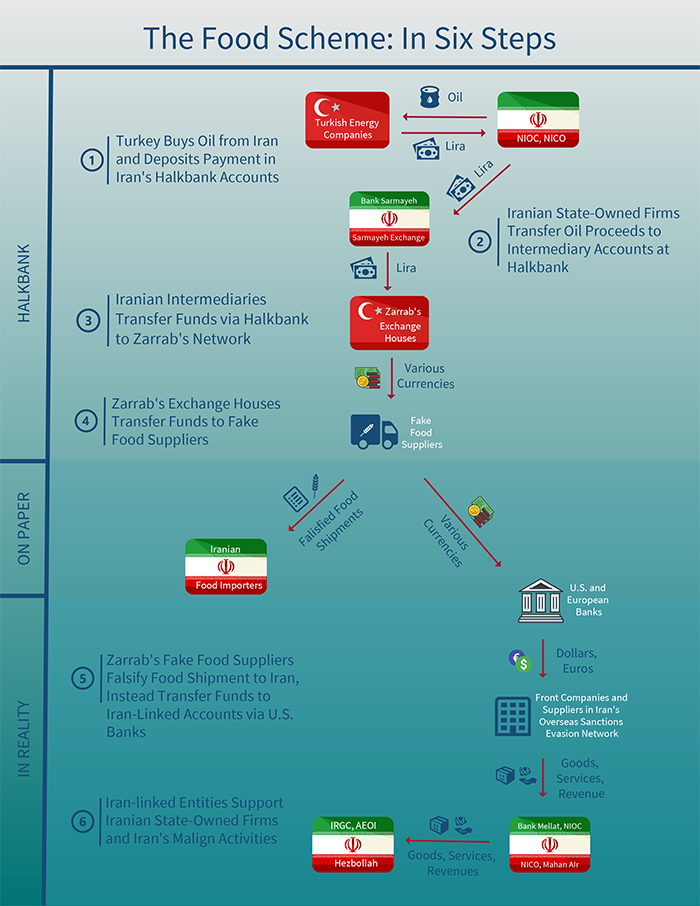

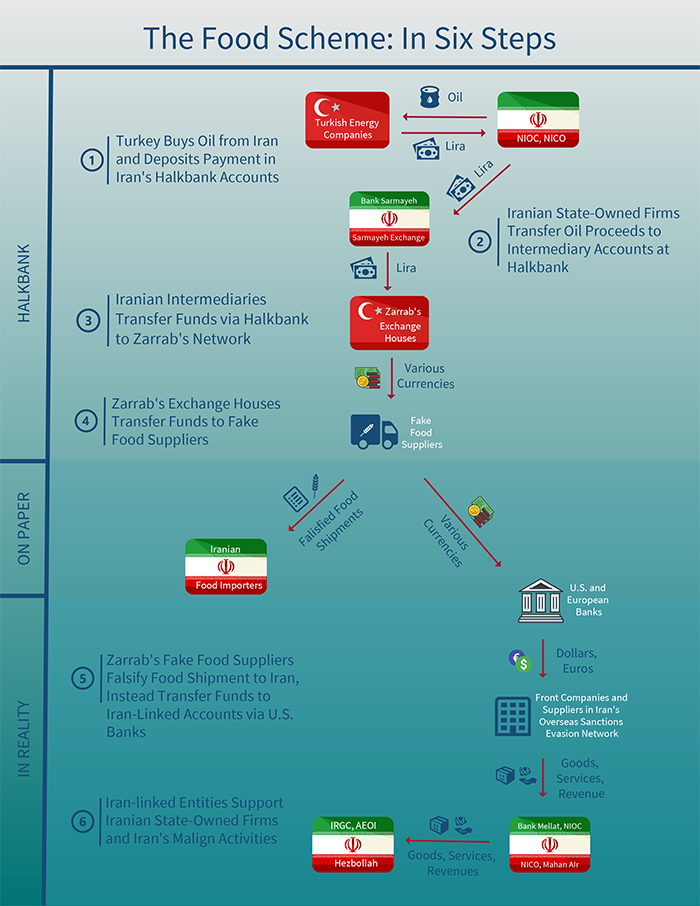

Restrictions from the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act of 2012 (IFCA) went into effect in July 2013, prohibiting the supply of precious metals to any Iranian entities, whether private or governmental.[34] This tightening of sanctions rendered the gold scheme untenable over the long term. Several months earlier, in anticipation of the change, Aslan suggested to Zarrab that he instead disguise his transfers using falsified records of food purchases.[35] Food exports to Iran are exempt from U.S. sanctions on humanitarian grounds, and Halkbank had facilitated food trade in the past, so its involvement would not appear overly suspicious.[36] Zarrab therefore arranged an April 2013 meeting in Turkey with Halkbank executives, Çağlayan, and NIOC officials Mahmoud Nikousokhan and Seifollah Jashnsaz, during which the conspirators hammered out the details of a new plan.[37]

The food scheme was more straightforward than the gold conspiracy, but it shared some similar characteristics. NIOC and CBI again transferred funds within Halkbank to intermediary accounts held by Iranian banks, which then moved the money to accounts held by Zarrab’s companies.[38] Zarrab concocted fake food purchases in Dubai using those funds, allowing him to transfer the money to his front companies in the UAE. To cover his tracks, Zarrab worked with Halkbank to create false shipping records indicating that food was subsequently exported to Iran. In reality, his front companies instead funneled the funds through the international financial system to entities in Iran’s sanctions evasions network, again at the direction of Iranian banks. The scheme was up and running by July 2013.[39]

Unlike the gold scheme where gold changed hands for cash on the open market in Dubai, nothing was ever actually bought or sold as part of the food scheme. The conspiracy therefore relied more heavily than before on false documentation to conceal the money’s true path. Zarrab could not forge bills of lading because they were too easily traceable, so instead he recorded the nonexistent food as being shipped on small wooden vessels that did not require them.[40] However, a cursory examination of financial documentation related to these shipments would have revealed the forgery. For example, Atilla had to warn Zarrab that it was not realistic to list a cargo weighing 150 thousand tons on a ship with a five-thousand ton capacity. Atilla also urged Zarrab to be careful about the purported origin of the goods. “Wheat doesn’t grow in Dubai,” he cautioned.[41]

Such missteps almost brought down the entire operation. In December 2013, Turkish law enforcement arrested Zarrab, Aslan, Çağlayan, and others on charges of bribery, corruption, money laundering, and gold smuggling after receiving a tip-off from a whistleblower.[42] Investigators found millions of dollars in bribes stashed in shoeboxes at Aslan’s residence and discovered documents detailing the scheme. Çağlayan, Aslan, and several other Halkbank and Turkish government officials were dismissed from their positions.[43] The case made international headlines, largely because it implicated Erdoğan.[44] The Turkish justice system did not see the case through to a conclusion, however. Zarrab bribed his way out of prison in February 2014 and the case against him was dismissed that October.[45]

Soon after his release, Zarrab began pressuring Halkbank’s new general manager Ali Fuat Taşkesenlioğlu to restart the food operation. Taşkesenlioğlu initially resisted, but was convinced when Erdoğan and his son-in-law, then-Minister of Energy Berat Albayrak, intervened on Zarrab’s behalf. [46] The food scheme continued until at least March 2016, when Zarrab was arrested in the United States.[47]

Links to Iran’s Nuclear and Missile Proliferation

According to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the tactics used by Halkbank and the other indicted and convicted co-conspirators in the case are hallmarks of proliferation finance: the transfer of funds to front company accounts, falsified invoices and bank records masking the transfers as legitimate sales, and the use of these funds to make international transactions on behalf of a proliferating state. De facto, this allowed Iran to access the international banking system, from which Iranian banks were barred due to sanctions.[48]

The schemes aided Iran’s proliferation activities in two ways. First, it benefitted Iranian entities with ties to those activities. In both the gold and food scheme, the laundered funds’ ultimate destination was to foreign companies participating in Iran’s sanctions evasion and illicit procurement networks. These companies supplied Iranian entities with goods and services, but needed to be paid in order to continue their operations; the Iranian oil money laundered through Halkbank was their payment. In one illustrative example, Zarrab’s companies made several international transfers – at the direction of Iranian banks and apparently on behalf of NIOC – to a Turkmenistan-based energy company that was supplying gas to Iran.[49]

Iranian entities that purchased goods and services in this manner included NIOC, NICO, Hong Kong Intertrade Company (HKICO), Bank Sarmayeh, Bank Mellat, and Mahan Air.[50] These entities have links to the full spectrum of Iran’s proliferation activities. For instance, NIOC was designated by the U.S. Treasury in November 2012 for providing “important technological and commercial support” to the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), [51] a principle agent of Iran’s missile program.[52] The IRGC was designated by the Department of State in October 2007 for its own role in financing proliferation, and some 15 individuals and organizations associated with the IRGC are currently subject to U.N. sanction.[53] Bank Mellat was also designated in October 2007, for providing banking services to the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), the main actor in Iran’s nuclear program.[54] For its part, Mahan Air was designated by the United States in October 2011 for providing support to the IRGC,[55] and again in December 2019 for its support of proliferation, including the transport of export-controlled missile and nuclear materials to Iran.[56] Between 2011 and 2019, numerous Mahan Air affiliates and aircraft were sanctioned by the United States for similar activity.

Second, the scheme relieved financial pressure on Iran between 2012 and 2016, amidst multilateral negotiations to limit Iran’s nuclear program that resulted in the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The pressure from sanctions provided critical leverage to the U.S. and its partners during negotiating with Iran. The financial back-channel provided by Zarrab and Halkbank may have lessened this leverage.[57]

U.S. Investigation and Prosecution

Zarrab’s arrest triggered the opening of the U.S. criminal case, which has unfolded in four stages. In the first stage, which lasted from March 2016 to March 2017, Zarrab was the main defendant, along with his employee Camelia Jamshidy and Bank Mellat official Hossein Najafzadeh (Jamshidy and Najafzadeh remain at large). They were indicted in the Southern District of New York on four charges: conspiracy to defraud the United States, conspiracy to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), conspiracy to commit bank fraud, and conspiracy to commit money laundering.[58] Zarrab tried and failed to have the indictment dismissed on the grounds that, as a non-U.S. national, “he [was] free to engage in transactions with Iranian businesses without running afoul of U.S. laws that criminalize U.S. sanctions against Iran.”[59] In November 2016, Zarrab’s brother and co-conspirator, Mohammad Zarrab (who remains at large), was added as a defendant.[60]

The second stage began with the arrest of Atilla in March 2017 and lasted until his sentencing in May 2018. A superseding indictment in September 2017 added four defendants – Aslan, Balkan, Caglayan, and Abdullah Happani, another of Zarrab’s employees – as well as substantive charges of bank fraud and money laundering against each defendant.[61] All except Atilla and Zarrab remain at large. Sometime during this period, Zarrab began to cooperate with U.S. investigators. He entered a guilty plea in October 2017 and testified at Atilla’s trial in November that year.[62] Atilla fought the charges against him unsuccessfully and was convicted in January 2018 on five of six counts and sentenced to 32 months in prison.[63]

The third stage, from May 2018 until October 2019, reflected a lull in the case. Zarrab had pleaded guilty, Atilla had been convicted and sentenced, and the other defendants remained at large. With jail time served during the trial included in his sentence, Atilla was released and deported back to Turkey in July 2019. Shortly thereafter, the Turkish government appointed him to lead Borsa Istanbul, Turkey’s main stock exchange.[64] Turkey, led by President Erdogan, meanwhile reportedly lobbied the Trump administration to drop the case. This effort led President Trump to refer the matter to the Attorney General and the Secretary of the Treasury but does not appear to have impacted the trajectory of the case.[65]

The fourth stage, from October 2019 to the present, began when Halkbank’s criminal indictment was unsealed by the Justice Department. The prosecution of a bank for sanctions violations is highly unusual. In their sentencing memorandum for Atilla, U.S. prosecutors cited nine sanctions violations cases against banks that had resulted in deferred prosecution agreements. Under such agreements, these banks avoided going to court by paying a fine and taking remedial action. Only one case cited, U.S.A. v. BNP Paribas, went further, and it ended in a plea bargain with a similar fine and remedial actions taken by the bank.[66] If Halkbank goes to trial, it will be the first bank to do so.

In their argument against Atilla, U.S. prosecutors asserted that Halkbank’s conduct was different from that of other banks accused of sanctions violations, which often self-report the violation, cooperate with authorities, and undertake significant internal reforms, whereas Atilla and other Halkbank employees systematically covered up evidence and continued to violate sanctions.[67] Nonetheless, U.S. Attorney General William Barr reportedly urged Halkbank to accept a deferred prosecution agreement, which Halkbank reportedly refused on the grounds that doing so would amount to an admission of guilt.[68] Halkbank lawyers are seeking to dismiss the case and bank representatives have declined to appear in court.[69] Zarrab, who also helped corroborate the case against Halkbank, reportedly continues to cooperate with the U.S. Department of Justice on this case.[70]

Conclusion

The Halkbank case is unprecedented, both in terms of the magnitude of the scheme – Halkbank and Zarrab laundered approximately $20 billion worth of Iranian funds[71] – and in terms of aggressive U.S. sanctions enforcement policy – as the first major bank to be indicted for sanctions evasion.

Iran is once again in the grip of severe U.S. sanctions and may soon face additional multilateral sanctions. Iran has abandoned the JCPOA’s limit on uranium enrichment, which could result in the re-imposition – or “snapback” – of all previous U.N. sanctions. In this context, Iran may once again turn to sanctions-busting arrangements abroad to continue its proliferation activities and keep its economy afloat.

If the U.S. justice system hands down a stiff penalty to Halkbank, a major sanctions violator that carried on its activities with the backing of the Turkish state, it may deter other foreign individuals and financial institutions from laundering money for Iran. If Halkbank instead gets off lightly, it may have the opposite effect. Bankers, businessmen, and officials in Iran, Turkey, and across the world will be eyeing the outcome.

Appendix

| Reza Zarrab's Network |

| Entity Name | Description and Role |

| Companies |

| Al Nafees Exchange | Dubai-based money services company; transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Asi Kiymetli Madenler Turizm Otom | Turkey-based money services company; transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Atlantis Capital General Trading | Dubai-based front company; fake food seller, transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Centrica | Dubai-based front company; fake food seller, transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Durak Doviz/Duru Doviz | Turkey-based money services company; transferred money to other Zarrab companies. |

| ECB Kuyumculuk Ic Vedis Sanayi Ticaret Limited Sirketi | Turkey-based money services company; transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Flash Doviz | Turkey-based money services company; transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Gunes General Trading LLC | Dubai-based money services company; transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Hanedan General Trading LLC | Dubai-based front company; transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Royal Denizcilik | Turkey-based gold trading company; purchased and sold gold. |

| Royal Emerald Investment | Turkey-based money services company; transferred money to Iran-linked entities. |

| Royal Holding A.S. | Turkey-based holding company for Safir Altin Ticaret, Royal Denizcilik, and Royal Emerald Investment. |

| Safir Altin Ticaret | Turkey-based gold trading company; purchased and sold gold. |

| Sam Exchange | Dubai-based money services company. |

| Volgam | Turkey-based front company; fake food trader, transferred money to other Zarrab companies. |

| Individuals |

| Abdullah Happani | Employee of Durak Doviz; resident of Turkey; conducted transfers on behalf of Reza Zarrab |

| Camelia Jamshidy | Employee of Royal Holding A.S.; resident of Turkey; conducted transfers on behalf of Reza Zarrab. |

| Mohammad Zarrab | Brother of Reza Zarrab; resident of Turkey; controlled Flash Doviz, Sam Exchange, and Hanedan General Trading LLC |

| Reza Zarrab | Mastermind of scheme; resident of Turkey; arrested in United States in 2016. |

| Turkish Entities |

| Entity Name | Description and Role |

| Companies |

| Halkbank | Facilitated the scheme throughout. |

| Arap Turk Bank | Allegedly conspired to participate in moving Iranian oil money from India to Halkbank. |

| Vakif Bank | Allegedly conspired to join the scheme with Prime Minister Erdogan's approval. |

| Ziraat Bank | Allegedly conspired to join the scheme with Prime Minister Erdogan's approval. |

| Individuals |

| Ali Fuat Taskesenlioglu | General manager of Halkbank after Aslan's dismissal until the collapse of the scheme; facilitated the scheme. |

| Berat Albayrak | Turkish Energy Minister from 2015 until the end of the scheme; Erdogan's son in law; pressed Turkish entities to cooperate. |

| Levent Balkan | Assistant deputy manager of Halkbank for international banking; assisted Atilla in supervising the scheme. |

| Mehmet Hakan Atilla | Deputy general manager of Halkbank for international banking; directly supervised the scheme; arrested in the United States in 2017; convicted in U.S. court in 2018; released to Turkey in 2019. |

| Mehmet Zafer Caglayan | Turkish Economy Minister until December 2013; accepted bribes from Zarrab pressed Turkish entities to cooperate with scheme. |

| Recep Tayyip Erdogan | Turkish Prime Minister during the scheme; urged Caglayan to continue the scheme; pressed other Turkish entities to cooperate. |

| Suleyman Aslan | General manager of Halkbank from the start of the scheme until December 2013; accepted bribes from Zarrab; facilitated the scheme. |

| Iranian Entities |

| Entity Name | Description and Role |

| Companies |

| Bank Mellat | Directed international money transfers on behalf of the Iranian government. |

| Bank Melli | Directed international money transfers on behalf of the Iranian government. |

| Bank Saderat | Directed international money transfers on behalf of the Iranian government. |

| Bank Sarmayeh | Held accounts at Halkbank that were used as intermediaries for Iranian government funds; directed international money transfers on behalf of the Iranian government. |

| Bank Shahr | Held accounts at Halkbank that were used as intermediaries for Iranian government funds. |

| Central Bank of Iran (CBI) | Held accounts at Halkbank that were the source of funds used in the scheme. |

| Mellat Exchange | Money service subsidiary of Bank Mellat; directed international money transfers on behalf of the Iranian government. |

| Naftiran Intertrade Company (NICO) | Held accounts at Halkbank that were the source of funds used in the scheme. |

| National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) | Held accounts at Halkbank that were the source of funds used in the scheme. |

| Parsian Bank | Held accounts at Halkbank that were used as intermediaries for Iranian government funds. |

| Sarmayeh Exchange | Money service subsidiary of Bank Sarmayeh; held accounts at Halkbank that were used as intermediaries for Iranian government funds; directed international money transfers on behalf of the Iranian government; proposed the scheme to Zarrab. |

| Individuals |

| Ahmad Ghalebani | Managing director of NIOC; held meetings with Zarrab and Halkbank officials. |

| Hossein Najafzadeh | Senior official at Mellat Exchange, directed international money transfers on behalf of the Iranian government. |

| Mahmoud Nikousokhan | Finance director of NIOC; held meetings with Zarrab and Halkbank officials. |

| Seifollah Jashnsaz | Chairman of NICO; held meetings with Zarrab and Halkbank officials. |

John Caves is a research associate at the Wisconsin Project. He is responsible for a project on Iran sanctions, which includes analysis of Iran’s proliferation and sanctions evasion networks. Meghan Peri Crimmins is Deputy Director of the Wisconsin Project and oversees the organization’s work on sanctions and counterproliferation finance. Simon Mairson, a former Research Assistant, contributed research to this report and worked on its early drafts.

Attachment:

Major Turkish Bank Prosecuted in Unprecedented Iran Sanctions Evasion Case

Major Turkish Bank Prosecuted in Unprecedented Iran Sanctions Evasion Case

Footnotes:

[1] H.R.4695 – Protect Against Conflict by Turkey Act, 116th U.S. Congress, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/4695, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[2] S.2644 – Countering Turkish Aggression Act, 116th U.S. Congress, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/2644, accessed on February 20, 2020; S.2641 – Promoting American National Security and Preventing the Resurgence of ISIS Act, 116th U.S. Congress, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/2641, accessed on February 20, 2020; William Roberts, “Senators to temporarily halt push for sanctions on Turkey: Graham,” Al Jazeera, October 22, 2019, available at https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/senators-temporarily-halt-push-sanctions-turkey-graham-191023000844816.html, accessed on March 30, 2020.

[3] “Trump-Erdogan Call Led to Lengthy Quest to Avoid Halkbank Trial,” Bloomberg, October 16, 2019, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-16/trump-erdogan-call-led-to-lengthy-push-to-avoid-halkbank-trial, accessed February 19, 2020.

[4] Transcript of Proceedings as to Mehmet Hakan Atilla re: Trial held on 11/30/17 before Judge Richard M. Berman, United States of America v. Mehmet Hakan Atilla, Case No. 1:15-cr-00867-RMB, Southern District Court of New York, Document No. 406, January 12, 2018, pp. 414-415, 421-422, available via PACER, accessed on March 3, 2020.

[5] Brief, United States of America v. Mehmet Hakan Atilla et al., Case No: 18-1910, Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, December 6, 2018, p. 3, available via PACER, accessed on October 24, 2019.

[6] Superseding Indictment, United States of America v. Reza Zarrab et al., Case No: 1:15-cr-008670-RMB, Southern District of New York, September 6, 2017, pp. 12-13, available via PACER, accessed on October 24, 2019.

[7] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Reza Zarrab et al., pp. 31-32; “Iran List (last amended 16 February 2011),” Export Control Organisation, United Kingdom’s Department for Business Innovation & Skills, p. 8, accessed via web.archive.org at https://web.archive.org/web/20101213122611/http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/biscore/eco/docs/iran-list.pdf on November 11, 2019.

[8] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., pp. 12-13, 32.

[9] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., p. 10; Council Regulation (EU) No 267/2012 of 23 March 2012 concerning restrictive measures against Iran and repealing Regulation (EU) No 961/2010, p. 108, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02012R0267-20150408&qid=1436811335282&from=EN, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[10] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., p. 33.

[11] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., pp. 13-14.

[12] Superseding Indictment, United States of America v. Halkbank, Case No: 1:15-cr-00867-RMB, Southern District of New York, October 15, 2019, p. 15, available via PACER, accessed on October 24, 2019.

[13] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., p. 6.

[14] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., p. 6-7.

[15] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, pp. 3, 10, 14.

[16] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, p. 16.

[17] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, pp. 19-20.

[18] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, pp. 4-5.

[19] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, pp. 15-16.

[20] Sentencing Memorandum, United States of America v. Mehmet Hakan Atilla, Case No: 1:15-cr-00867-RMB, April 4, 2018, p. 7, available via PACER, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[21] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, pp. 14-15.

[22] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., pp. 8-9, 15-16.

[23] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., pp. 30-32.

[24] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, pp. 4, 15, 34.

[25] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, p. 26

[26] Brief, United States of America v. Mehmet Hakan Atilla et al., Case No: 18-1910, Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, December 6, 2018, p. 9, available via PACER, accessed on October 24, 2019; Transcript of Proceedings as to Mehmet Hakan Atilla re: Trial held on 11/30/17, U.S.A. v. Atilla, pp. 384-388.

[27] Transcript of Proceedings as to Mehmet Hakan Atilla re: Trial held on 11/30/17, U.S.A. v. Atilla, pp. 449-451, 453.

[28] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, pp. 16-17.

[29] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, p. 25.

[30] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., pp. 14-15.

[31] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, p. 22; Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., pp. 20-21.

[32] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, p. 24.

[33] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., p. 22.

[34] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, pp. 10, 24.

[35] Transcript of Proceedings as to Mehmet Hakan Atilla re: Trial held on 11/30/17, U.S.A. v. Atilla, pp. 493-495.

[36] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., p. 10.

[37] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, p. 28.

[38] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., pp. 11-12.

[39] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., p. 12.

[40] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., p. 11.

[41] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., pp. 12-13.

[42] Berivan Orucoglu, “Why Turkey’s Mother of All Corruption Scandals Refuses to Go Away,” Foreign Policy, January 6, 2015, available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/06/why-turkeys-mother-of-all-corruption-scandals-refuses-to-go-away/, accessed on November 1, 2019.

[43] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., p. 23.

[44] Orucoglu, “Why Turkey’s Mother of All Corruption Scandals Refuses to Go Away.”.

[45] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Halkbank, p. 33.

[46] Brief, U.S.A. v. Atilla et al., p. 24; “Turkey’s Erdogan son-in-law made finance minister amid nepotism fears,” BBC, July 10, 2018, available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-44774316, accessed on February 20, 2020.

[47] “Turkish National Arrested for Conspiring to Evade U.S. Sanctions Against Iran, Money Laundering and Bank Fraud,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 21, 2016, available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/turkish-national-arrested-conspiring-evade-us-sanctions-against-iran-money-laundering-and, accessed on March 5, 2020.

[48] “National Proliferation Financing Risk Assessment,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2018, pp. 23-24, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/2018npfra_12_18.pdf, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[49] Transcript of Proceedings as to Mehmet Hakan Atilla re: Trial held on 11/30/17, U.S.A. v. Atilla, pp. 431; Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., p. 30-31.

[50] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al., p. 29.

[51] “Treasury Sanctions Iranian Government and Affiliates,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, November 8, 2012, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/tg1760.aspx, accessed on March 6, 2020.

[52] “Designation of Iranian Entities and Individuals for Proliferation Activities and Support for Terrorism,” U.S. Department of State, October 25, 2007, available at https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2007/oct/94193.htm, accessed on March 30, 2020.

[53] “Security Council Sanctions List Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2231,” United Nations, available at https://scsanctions.un.org/r/?keywords=iran, accessed on March 30, 2020.

[54] “Fact Sheet: Designation of Iranian Entities and Individuals for Proliferation Activities and Support for Terrorism,” Press Release, October 25, 2007, U.S. Department of the Treasury, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/hp644.aspx, accessed on March 6, 2020.

[55] “Treasury Designates Iranian Commercial Airline Linked to Iran’s Support for Terrorism,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 12, 2011, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/tg1322.aspx, accessed on March 30, 2020.

[56] “Designation of the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines, E-Sail Shipping Company Ltd, and Mahan Air Fact Sheet,” U.S. Department of State, December 11, 2019, available at https://www.state.gov/designation-of-the-islamic-republic-of-iran-shipping-lines-e-sail-shipping-company-ltd-and-mahan-air/, accessed on March 26, 2020.

[57] “Turkish Banker Mehmet Hakan Atilla Sentenced To 32 Months For Conspiring To Violate U.S. Sanctions Against Iran And Other Offenses,” U.S. Department of Justice, May 16, 2018, available at https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/turkish-banker-mehmet-hakan-atilla-sentenced-32-months-conspiring-violate-us-sanctions, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[58] Indictment, United States of America v. Reza Zarrab, Camelia Jamshidy, and Hossein Najafzadeh, Case No: 1:15-cr-00867-RMB, Southern District of New York, Document 2, December 15, 2015, available via PACER, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[59] Decision and Order, United States of America v. Reza Zarrab, Case No: 1:15-cr-00867-RMB, Southern District of New York, Document 90, October 17, 2016, pp. 2-4, available via PACER, accessed on March 6, 2020.

[60] Superseding Indictment, United States of America v. Reza Zarrab, Mohammad Zarrab, Camelia Jamshidy, and Hossein Najafzadeh, Case No: 1:15-cr-008670-RMB, Southern District of New York, Document 106, November 7, 2016, available via PACER, accessed on March 6, 2020.

[61] Superseding Indictment, U.S.A. v. Zarrab et al.

[62] Transcript of Proceedings as to Mehmet Hakan Atilla re: Trial held on 11/30/17, U.S.A. v. Atilla

[63] “Judgment in a Criminal Case,” United States of America v. Mehmet Hakan Atilla, Case No: 1:15-cr-00867-RMB, Southern District of New York, Document 518, May 16, 2018, available via PACER, accessed on March 3, 2020

[64] Ayla Jean Yackley, “Turkey picks former jailed banker to head Istanbul stock exchange,” Financial Times, October 21, 2019, available at https://www.ft.com/content/31e25da8-f442-11e9-a79c-bc9acae3b654, accessed on November 1, 2019.

[65] Letter from Senator Ron Wyden to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, October 24, 2019, available at https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/102319 Halkbank–Mnuchin.pdf, accessed on February 19, 2020; Treasury Response to Senator Wyden’s Letter, November 20, 2019, available at https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/112019 Treasury Response Letter to Wyden RE Halkbank.pdf, accessed on February 19, 2020.

[66] “Government’s Sentencing Memorandum,” United States of America v. Mehmet Hakan Atilla, Case No. 1:15-cr-00867-RMB, Southern District Court of New York, Document 505, April 4, 2018, pp. 51-53, available via PACER, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[67] “Government’s Sentencing Memorandum,” U.S.A. v. Atilla, pp. 51.

[68] “Trump-Erdogan Call Led to Lengthy Quest to Avoid Halkbank Trial,” Bloomberg, October 16, 2019, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-16/trump-erdogan-call-led-to-lengthy-push-to-avoid-halkbank-trial, accessed February 19, 2020.

[69] Brendan Pierson, “Halkbank says it will seek dismissal of U.S. indictment, judge’s recusal,” Reuters, November 4, 2019, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-turkey-halkbank/halkbank-says-it-will-seek-dismissal-of-u-s-indictment-judges-recusal-idUSKBN1XE2CC, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[70] Heidi Przybyla, Julia Ainsley and Tom Winter, “As prosecutors raise pressure on Turkish bank, Erdogan likely to ask Trump to go easy,” NBC News, November 13, 2019, available at https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/prosecutors-raise-pressure-turkish-bank-erdogan-likely-ask-trump-go-n1080991, accessed on November 20, 2019.

[71] “Turkish Bank Charged in Manhattan Federal Court for Its Participation in a Multibillion-Dollar Iranian Sanctions Evasion Scheme,” U.S. Department of Justice, October 15, 2019, available at https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/turkish-bank-charged-manhattan-federal-court-its-participation-multibillion-dollar-iranian, accessed on March 6, 2020.