The New York Times

April 29, 2001, p. A8

Iraq tested a bomb in 1987 that cast a radioactive cloud in the open air and was designed to cause vomiting, cancer, birth defects and slow death, according to a secret Iraqi report on the weapon’s construction and testing.

Radiation sickness from the bomb, the document said, would “weaken enemy units from the standpoint of health and inflict losses that would be difficult to explain, possibly producing a psychological effect.” Death, it added, might occur “within two to six weeks.”

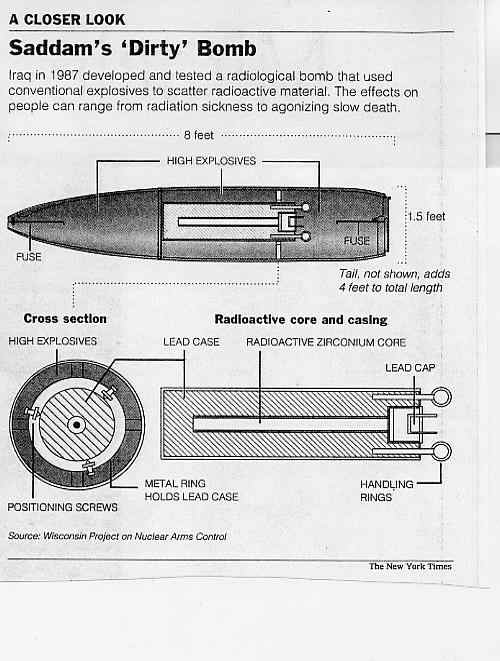

The bomb, 12 feet long and weighing more than a ton, according to the document, could be dropped on troop areas, industrial centers, airports, railroad stations, bridges and “any other areas the command decrees.”

While the existence of Iraq’s effort to build a radiological weapon has been known for several years, the 1987 report sheds light on the secret effort. The New York Times obtained the document from the Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control, a private group in Washington that said it acquired it from a United Nations official.

Radiation or radiological weapons, sometimes known as “dirty nukes,” are the poor cousins of nuclear arms. Their conventional high explosives scatter highly radioactive materials to poison targets rather than destroying them with blast and heat. Their effects on people can range from radiation sickness to agonizingly slow death, which is why military experts often see them as ethically bankrupt.

Radiation or radiological weapons, sometimes known as “dirty nukes,” are the poor cousins of nuclear arms. Their conventional high explosives scatter highly radioactive materials to poison targets rather than destroying them with blast and heat. Their effects on people can range from radiation sickness to agonizingly slow death, which is why military experts often see them as ethically bankrupt.

“It shows what kind of guy we’re dealing with,” said Gary Milhollin, the group’s director, of the Iraqi leader, Saddam Hussein. The bomb, he added, was “nasty stuff meant to kill people over a long period of time” and thus, he said, “crossed the line into moral barbarism.”

It was basically a dud, however, Mr. Milhollin said, and that caused the Iraqis to scrap the project. The radiation levels were considered too low to achieve the grisly objectives.

The episode nonetheless “shows Iraq’s intention” to develop weapons of mass destruction, he added. The official who disclosed the document, Mr. Milhollin said, is “concerned that Saddam is going to get the bomb.”

The United Nations rarely discloses documents gathered in Iraq, but David Albright, formerly a nuclear inspector in Iraq, said he had seen the document and that it he did not doubt it was authentic.

He and other experts agreed that the document, which is to be posted on a Web site Monday, gives away no secrets that could aid weapons development and no indication that the project was a resounding failure.

Nuclear experts say Iraq today has neither programs to develop radiological weapons nor the reactors needed to make radioactive materials for them, and no fuel for nuclear arms. The reactor used in making the prototype radiological weapon was itself bombed during the gulf war in 1991, and inspectors tried to keep Iraq from resuming its nuclear efforts for years afterward.

But today the inspectors are largely gone and American experts worry that Iraq may be quietly shopping for bomb fuel and parts on the international black market.

“There’s growing concern that Iraq is reconstituting its nuclear weapons program and will make steady progress because it knows so much already,” said Mr. Albright, president of the Institute for Science and International Security, an arms control group in Washington.

Iraq’s testing of its radiological weapon was done in 1987 as it waged a war of attrition against Iran and considered the radiation bomb as a way to cripple enemy forces. The document said the work was undertaken by Atomic Energy Agency and the Al Qa-Qa and Al Muthanna centers of the Iraqi Military Industrial Commission.

To make the radioactive materials, Iraqi engineers prepared special metals to irradiate in a reactor at Tuwaitha, Iraq’s primary nuclear site. The document said the metal was mostly zirconium, which is often used in atomic reactors because it resists corrosion. The zirconium mixture also included hafnium, uranium and iron.

Zirconium was chosen, the document said, because a production process for it already existed since the metal was used for incendiary bombs. When finely powdered, the metal ignites spontaneously in air.

The half-life of zirconium 95, the document said, was 75.5 days. This relatively short period of radioactive decay, it said, “helps to dissipate the effect of the bomb after several weeks so that it is difficult to track, analyze, or recognize.” The brevity, it added, gives “the desired biological effects” while making it “possible for our units to go to the bombed area without great danger after this period has expired.”

The document has many diagrams. They show at the bomb’s core a thick three-foot lead case, shielding workers from its radioactive rays, that held the zirconium. This leaden case fit inside an eight-foot casing that held fuses and explosive charges and was capped by tail fins four feet long.

The weapon and its parts were tested three times in 1987, the document said. The first sought to see if the thick lead case holding an irradiated charge could be blown apart, in order to discharge. It could.

The second test was of a bomb sitting on the ground. “The explosion was awesome,” said the report. “We saw the blast wave moving out of the center of the explosion in the form of a circle moving at great speed.” The radioactive cloud rose more than 600 feet.

In the third test, the Iraqi Air Force dropped two bombs, which again produced huge clouds. “We must point out,” the report said, “that a significant part of the fallout went with the cloud into the air and it was not possible to follow this small amount of radioactive matter by means of the portable equipment.”

Radiation readings on the ground were rather low, in one case “290 times above the highest level allowed nationally for foodstuffs.” The document reported no readings taken in the air — a critical oversight for a weapon meant to hurt and kill people largely through the inhalation of radioactive particles.

The main flaws of the weapon, the report said, were that its radioactive charges lost strength quickly. The irradiatiated charge had to be used within a week. Calm weather was also essential. Another drawback, it said, was that the work had to be done in strict secrecy, “even with regard to those doing the work, so as not to give rise to psychological feelings leading to hesitation because of a fear of radiation.”

A final problem, it said, was that an alert enemy might come to realize that the exploding bombs packed a lingering punch, allowing the future development of defensive precautions. It even suggested that satellites might be able to spot radiation from “a concentrated strike,” a feat that seems unlikely.

Iraq gave the document to the inspectors and the United Nations apparently referred to it in a April 1996 report of the United Nations special commission set up to monitor Iraq’s disarmament. “Iraq declared,” it said, “that no order to produce radiological weapons was given and the project was abandoned.”

The document is to be posted Monday at www.iraqwatch.org, a new initiative of the Wisconsin Project. The main supporter of the Web site is the Smith-Richardson Foundation, a private group in Westport, Conn., that specializes in issues of national security.

Mr. Milhollin of the Wisconsin Project said that the radiation effort was clearly a flop, despite the report’s upbeat language.

“When you read this, you get the impression that the guys in Iraq were trying to put best face on the results, to exaggerate them,” he said. “But if you look at the figures, it’s obvious it didn’t work.”