Introduction

After nearly seven years of fighting, it appears that the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad has gained the upper hand in Syria’s civil war, which has claimed nearly half a million lives.[1] In his ruthless campaign to hold on to power, Assad repeatedly has targeted civilian populations with chemical weapons. Since 2012, some 130 instances of chemical weapons use have been reported in Syria. The vast majority of the confirmed attacks have been attributed to the Assad regime.[2][3]

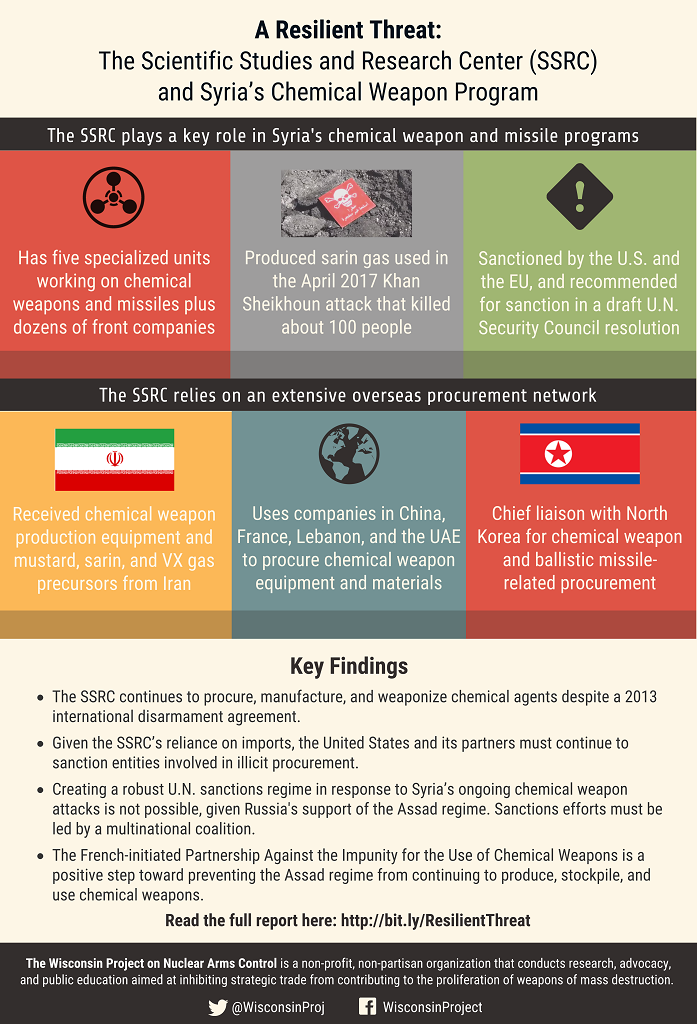

Two of the most deadly attacks involved sarin gas, a highly toxic nerve agent. The first occurred in August 2013 in the Damascus suburb of Ghouta. The Syrian military launched a barrage of rockets and artillery armed with sarin at a rebel-controlled area, killing over 1,400 people, including at least 426 children.[4] The second attack occurred in April 2017 in Khan Sheikhoun. In this attack the Syrian Air Force dropped aerial bombs containing sarin on a civilian area, killing approximately 100 people.[5]

The Scientific Studies and Research Center (SSRC), which oversees the production of chemical weapons in Syria, contributed to these attacks. The SSRC operates a number of facilities across Syria, where it produces chemical weapons, missiles, and artillery. It also relies on a network of companies inside and outside of Syria through which it procures the equipment and materials necessary for production. This network continues to operate despite U.S. and other government sanctions and international efforts to dismantle Syria’s chemical weapons.

This report describes the SSRC’s role in the development of Syria’s chemical weapons and chemical weapon delivery systems, as well as the structure and operation of its procurement network.

The History of SSRC Chemical Weapons Development

The SSRC was established in 1971. While it performs civilian duties, one of its primary functions is to oversee Syria’s chemical weapon and missile programs.[6] Due to its involvement in these activities, the SSRC has been publicly sanctioned by the governments of Australia, Canada, the European Union, Japan, Norway, South Korea, Switzerland, and the United States.[7] The organization was also recommended for sanction in a draft U.N. Security Council resolution in February 2017. The resolution was vetoed by Russia and China.[8]

Declassified U.S. intelligence documents indicate that before 1983, the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia provided Syria with chemical agents and relevant training.[9] According to a recent report in the French investigative journal Mediapart, which was based on interviews with exiled SSRC scientists, the SSRC also received support for chemical weapon development from entities in West Germany. In the 1970s and early 1980s, Syrian chemists trained at university labs and research centers in Germany. While such training had ceased by 1983, the SSRC continued to import German products for its chemical program well into the 2000s. These imports reportedly included sodium fluoride and hydrogen fluoride, which are used in the synthesis of sarin gas. In the late 1980s, Armenia also provided assistance, including a formula for VX nerve agent and a supply of VX precursors. SSRC was soon producing VX at a secret underground site near Al-Nabk, 75 kilometers northeast of Damascus. According to the exiled scientists, VX production continued at this facility, with few interruptions, until 2012.[10]

By the mid-2000s, Iran was reportedly helping Syria develop its chemical weapon program, providing the blueprints for facilities and equipment used to produce hundreds of tons of precursors for VX and sarin. Tehran has also reportedly supplied Damascus with chemicals that can be used to produce mustard gas, including ethylene glycol, sodium sulfide, and hydrochloric acid. One such exchange occurred in 2002, when Iran’s Defense Industries Organization (DIO) supplied the SSRC with 10 tons of monoethylene glycol (MEG), which can be converted into a precursor for mustard gas and VX.[11] In addition, Tehran is reportedly the primary foreign funder of the SSRC’s weapons activities, even paying for North Korea’s assistance to its chemical weapon program.[12]

The SSRC appears to be Syria’s chief liaison with North Korea for the illicit procurement of equipment and materials for chemical weapons and ballistic missiles. Pyongyang has reportedly been supporting Syria’s chemical weapon program, in the form of equipment and technical assistance, since at least the 1990s. This support is believed to have accelerated in 2007, and to have continued after the outbreak of the civil war.[13] In early 2013, for example, North Korea reportedly transferred a vacuum dryer, which is required to produce chemical weapons, to Syria.[14] According to a leaked report by a U.N. expert panel, the SSRC reportedly received some 40 shipments from North Korea between 2012 and 2017.[15]

In addition, North Korea and Iran have reportedly helped build and operate at least five chemical weapon facilities in Syria,[16] at which the SSRC has overseen the production of large quantities of chemical munitions.

The majority of Syria’s stockpile is composed of sarin nerve agent.[17] The SSRC developed a particular type of sarin that uses hexamine as a stabilizer. This hexamine is a key “signature” of SSRC-developed sarin. This sarin generates diisoproyl methylphosphonate (DIMP) as a byproduct. DIMP is the second “signature” of the SSRC variant.[18] These signatures make it possible to identify SSRC-developed sarin.

In addition, through 2013, Damascus had a stockpile of several hundred tons of mustard gas and several tens of tons of VX nerve agent, according to a report by the French government.

SSRC and Chemical Weapon Delivery Systems

Syria’s missile program, which is also overseen by the SSRC, developed alongside its chemical weapon program.[19] Its arsenal of chemical weapon-capable delivery systems include several variants of liquid-fueled Scud missiles, including from North Korea, solid-fueled missiles of Iranian and Russian origin, as well as artillery rockets and aircraft.[20]

Damascus reportedly first acquired missiles, including the 300 km liquid-fueled Scud B ballistic missile and the Frog-7 artillery rocket, from the Soviet Union in the 1970s. By the 1990s, it had added to its arsenal the liquid-fueled Scud C, which has a range of 500 km.[21] As with its chemical weapon program, Syria received extensive help from Iran and North Korea for missile development.

After acquiring the technology for the 700 km liquid-fueled Scud D from Pyongyang, Syria began producing the missile around 2000.[22] Between 2005 and 2008, North Korea sought to procure raw materials for Syria’s missile and rocket programs on behalf of Damascus, including graphite, nozzle throats, and titanium steel. North Korea also supplied the SSRC with specialty steel and other materials for Scud electronic systems procured from China.[23] Engineers from Pyongyang’s Tangun Trading Company reportedly work with SSRC personnel to integrate the chemical weapons into Scud missile warheads.[24]

Iran has been assisting Syria with missile development since the early 1990s. Iran has cooperated with the SSRC in the construction of solid and liquid propellant production facilities, and reportedly supplies solid propellant equipment and technical expertise. By 2007, Damascus had also acquired the solid-fueled Fateh-110 ballistic missile from Iran, which has a range of 200-300 km. The SSRC reportedly is producing its own version of this system, known as the M600.[25] The Iranian firms Shahid Hemat Industrial Group (SHIG) and Shahid Bakeri Industrial Group (SBIG) reportedly supply explosives, solid propellant-related technology, and technical expertise to the SSRC.[26]

Syria also has received the solid-fueled SS-21 “Tochka” ballistic missile, which has a range of 70 km. Russia reportedly delivered a shipment of some 50 of these missiles in early 2017.[27]

Crossing the Red Line: SSRC and the Use of Chemical Weapons

Exiled SSRC scientists report that in 2009, Damascus, alarmed by potential domestic unrest, ordered the SSRC to begin miniaturizing gas munitions for use against dissidents. It was also reportedly ordered that equipment for storing sarin precursors and arming munitions be set up at seven specially chosen air bases across Syria. In the summer of 2011, as the civil war was ramping up, personnel from the SSRC’s elite Branch 450 began to modify small scale munitions and prepare the sarin precursors for use at the bases.[28] By 2013, the SSRC had dispersed Syria’s chemical agents across many sites, with estimates ranging from 20 to 50.[29]

The first confirmed use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime occurred in April 2013, in the Aleppo region. Sarin was used in that attack. Since then, Damascus is assessed to have launched at least 29 attacks with chemical weapons.[i] Seven involved sarin, while the remainder involved chlorine.[30] In the August 2013 sarin attack in Ghouta, SSRC personnel prepared the munitions prior to their launch, and reportedly developed the short-range rockets used in the attack.[31]

Under a joint U.S.-Russian agreement reached shortly after the August 2013 attack, Damascus was required to destroy all of its chemical weapons production equipment by November of that year. Its entire chemical weapon stockpile was to be removed from the country by July 2014. The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) oversaw the implementation of this agreement.[32] In July 2014, the OPCW announced that all 1,300 metric tons of Syria’s declared stockpile had been removed.[33] By October 2017, the OPCW declared that 25 of the 27 chemical weapon production facilities declared by Syria had been destroyed (Syria requested assistance in the destruction of the remaining two facilities).[34]

Despite the OPCW’s efforts, reports soon emerged that Damascus had not surrendered its entire stockpile. OPCW officials reportedly found traces of undeclared VX and sarin at an SSRC facility in 2015.[35] That same year, international inspectors and officials told the Wall Street Journal that the Syrian government obstructed efforts to inspect its chemical facilities, leading U.S. intelligence agents to conclude that Syria had not surrendered its entire stockpile. Officials also said that Syria used its chemical labs to produce weaponized chlorine as the removal process occurred.[36] In October 2017, the OPCW reported that the SSRC still has not provided a complete declaration of its facilities and activities.[37]

The French and U.S. governments suspect that Damascus still has a stockpile of the sarin precursor methylphosphonyl difluoride (DF), the capacity to produce and stockpile sarin, as well as chemical-capable rockets and grenades.[38] An exiled SSRC employee estimates that the organization hid 35 metric tons[ii] of poison gas from the OPCW.[39]

Chemical weapon production under the SSRC continues. A report by a Western intelligence agency leaked to the BBC in May 2017 states that the organization is producing chemical weapons at three sites: Masyaf in Hama province, and two facilities near Damascus – Dummar (also known as Jamraya) and Barzeh. The chemical weapons are reportedly installed on artillery and long range missiles at Masyaf and Barzeh. While OPCW inspectors are present at the two sites near Damascus, they do not have access to all areas, and the weapons are reportedly produced in the restricted sections. The intelligence report also assesses that Russia and Iran are aware of Syria’s illicit activities.[40] The Israeli Air Force has reportedly conducted numerous airstrikes on these facilities over the past year, including at least three on Jamraya and one on Masyaf. It is not clear if these strikes have disrupted Syria’s chemical weapon production.[41]

Chemical weapons produced by the SSRC continue to be used by the Assad regime. Samples taken from Khan Sheikhoun following the April 2017 attack revealed the presence of hexamine and DIMP, the two “signatures” of SSRC sarin.[42] The Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM), established by the UN and the OPCW to investigate chemical weapons use in Syria, assesses that the sarin used in the attack was produced with the DF that came from Syria’s original stockpile.[43]

SSRC engineers also build barrel bombs used by the Syrian armed forces against civilian populations. These barrel bombs were used in chlorine gas attacks via helicopter on several occasions between 2014 and 2015. Since the beginning of 2018, suspected chlorine attacks have occurred in Eastern Ghouta and in Saraqeb, resulting in a number of casualties and at least six deaths.[44] The chlorine used in Saraqeb allegedly was delivered using barrel bombs dropped from a helicopter.[45]

A Resilient Network: SSRC’s Production and Procurement

It is difficult to get a clear picture of the SSRC’s structure and how it uses affiliates, front companies, and procurement agents. Media and government reports have shed some light on how it is organized. Other subdivisions have been identified in open sources. According to these reports, the SSRC has five specialized units working on chemicals weapons and their delivery vehicles:

- Division 1000 (Damascus) – development of navigation and guidance systems, as well as other electronics

- Division 2000 (Damascus) – engineering and production of launchers for rockets and missiles

- Branch 410 – production of electronic and mechanical systems

- Division 3000 (Baza) – development and production of chemical and biological weapons

- Department 3100 – synthesis of chemical weapons and their antidotes; chemical weapon detection and decontamination

- Department 3600 – production of chemical weapons

- Branch 450 – storage, guarding, and deployment of Syria’s chemical weapon stockpile

- Division 4000 (Aleppo) – oversight of all of Syria’s aviation, missile, and rocket programs

- Project 99 – development of Scud missiles in cooperation with North Korea

- Project 111 – development of surface-to-air missiles

- Project 350 – production of surface-to-surface rockets and missiles

- Project 702 – development of solid propellants, including for the M600, in cooperation with Iran

- Advanced Institute of Applied Sciences and Technology (ISSAT) – civilian programs[46]

The SSRC also oversees two major subsidiaries, both of which have been sanctioned by the United States and the European Union. They were also recommended for sanction by the United Nations in the February 2017 draft Security Council resolution:

- Higher Institute of Applied Science and Technology (HIAST)

- National Standards and Calibration Laboratory (NSCL)[47]

In addition, the SSRC has cultivated a network of front companies and procurement firms (see appendix), many of which also have been sanctioned by the United States and the European Union, notably the General Establishment for Engineering Industries (Handasieh). This firm oversees a group of about 12 engineering firms and has been connected to a number of missile-related shipments from North Korea. Handasieh also sought a casting molding line for a Scud missile project from Iran in 2010.[48]

In the years preceding the civil war, SSRC used its supply network in an effort to import equipment and material necessary for chemical weapon and ballistic missile production, often from Iran and North Korea. Interdicted items destined for SSRC front companies included solid double-base propellant,[49] chemical protection gear,[50] brass discs used to produce artillery ammunition tubes,[51] and machinery used in the production of liquid propellants.[52]

The U.S. Treasury Department also reports that in 2009 and 2010, Mechanical Construction Factory (MCF), one such front company, received components used in the production of solid propellant for rockets and missiles from Iran. Another SSRC front, Business Lab, also sought to procure 500 liters of pinacolyl alcohol, which is a precursor for the nerve agent soman, in 2009.[53]

In 2008, an SSRC affiliate attempted to purchase items that can be used to produce chemical weapon agents from two chemical firms in India. These items included glass components, chemical processing equipment, and heat exchangers.[54]

The SSRC’s procurement network has continued to operate despite the disarmament agreement and OPCW dismantlement work. According to the French government, since 2014 Syria has attempted to acquire dozens of tons of isopropanol, which is used in the manufacture of sarin.[55] Also since 2014, Western governments have identified over 30 SSRC front companies and procurement agents (see appendix for the complete list). In addition, the United States sanctioned 271 SSRC officials in a single action taken in April 2017.[56]

The SSRC uses these entities to make weapon-related procurements, including sarin gas precursors.[57] Such procurements have also reportedly included electronic components, computer numerically-controlled (CNC) machines, and raw materials.[58] In addition, the SSRC has recently sought to procure items under its own name, including carbon dioxide cylinders, cutting machinery,[59] and measuring equipment.[60]

One the most active SSRC front companies, the Metallic Manufacturing Factory (MMF), has issued at least two separate tenders for ammonium nitrate, which can be used as an oxidizer in missile propellants, and can also be used in explosives. The first tender, issued in July 2017, requested 700 tons of ammonium nitrate. The second, issued in January 2018, requested 1,000 tons.[61] Last year, MMF also sought to procure detonators[62] and a number of items with missile production applications, including a CNC lathe.[63] Earlier, in 2014, it sought to procure materials for making gas masks.[64]

The SSRC also has relied on entities based overseas to procure sensitive items on its behalf. For example, in July 2016 the United States sanctioned a Dubai-based network run by Salah Habib. This network acquired and shipped “sensitive merchandise and war materials” to the SSRC. In the same month, the United States targeted the Mahrous Group, another Dubai-based network, for making payments on behalf of SSRC to its foreign suppliers.[65]

Conclusion

Syria has not abandoned chemical weapons despite the partial disarmament in 2013-2014. This is demonstrated by the Assad regime’s continued use of these weapons as well as ongoing efforts, led by the SSRC, to obtain chemical weapon precursors and other weapon-related items.

Unfortunately, creating a robust U.N. sanctions regime in response is not possible, given Russia’s support of the Assad regime. Russian opposition doomed the Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM), which was established by the United Nations and the OPCW in August 2015 to investigate chemical weapons use in Syria. The JIM was terminated in late 2017 after Russia vetoed a series of Security Council resolutions which would have extended its mandate. During its tenure, the JIM issued reports implicating the Assad regime in four chemical weapon attacks: Khan Shaykhun in April 2017 (sarin); Sarmin in March 2016 (chlorine); Qmenas in March 2015 (chlorine); and Talmenes in April 2014 (chlorine).[66]

Thus, sanctions must be imposed by a multinational coalition. Given the SSRC’s reliance on foreign sources, the United States and its partners must continue to identify entities inside and outside of Syria supporting illicit procurement. The French government took such a step last January, identifying two networks comprised of dozens of entities that acted on behalf of the SRRC to procure chemical weapon material, including sarin gas precursors.[67] The entities in these networks operate from China, France, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates, as well as from Syria.

The French-initiated Partnership Against the Impunity for the Use of Chemical Weapons, which was launched in Paris in January 2018, is another positive step. The partnership is dedicated to identifying and holding accountable entities that use or proliferate chemical weapons. It has set up a database drawn from national sanctions lists that provides the names of entities involved in chemical weapon use and proliferation. The partnership currently consists of around 30 countries and international organizations, including the United States.[68] Initiatives such as these will be essential to hold the Assad regime accountable and to prevent it from continuing to produce, stockpile, and use chemical weapons in the future.

Appendix^

Entities Identified as SSRC Fronts or Procurement Agents Since 2011

ABC Shipping Co. (Lebanon) [69]

Aziz Allouch (Nationality: Unknown) [70]

Business Lab (Syria)[71]

Chahine Mireille (Nationality: Lebanese) [72]

Denise Company (Lenanon)[73]

EKT Smart Technology (China)

Electronic Katrangi Trading (EKT) (Lenabon)

Electronic System Group (ESG) (Syria) [74]

Expert Partners (Syria)

General Establishment for Engineering Industries (Handasieh)[75]

Golden Star Co. (Syria)

Houranieh Chadi (Nationality: Canadian)

Houranieh Fadi (Nationality: Syrian)

Houranieh Hwaida (Nationality: Canadian)

Houranieh Mohammad Khalil (Nationality: Syrian)

Houranieh Mohammad Nazier (Nationality: Canadian) [76]

Industrial Solutions (Syria)[77]

Joud Trading (UAE)

Kassoum Mohamed (Nationality: Unknown)

Katrangi Amir Hachem (Nationality: Syrian)

Katrangi Houssam Hachem (Nationality: Lebanese)

Katrangi Maher Hachem (Nationality: Syrian)

Lumière Elysées (France) [78]

Mahrous Group (Syria)[79]

Mahrous Trading FZE (UAE)

Mechanical Construction Factory (MCF)[80]

Megatrade (Syria)[81]

Metallic Manufacturing Factory (MMF) (Syria)[82]

MHD Nazier Houranieh & Sons Co (Syria)

MKH Import & Export (Syria)

NKTRONICS (Lenanon) [83]

Organization for Technological Industries (OTI) (Syria)[84]

Salah Habib (Nationality: French and Syrian) [85]

Shadi for Cars Trading (Lebanon)

Sigma Tech Company (Syria) [86]

Smart Green Power (France)

Smart Logistics Offshore (Lenanon)

Smart Pegasus (France)

Steelor Company (Lebanon) [87]

Syrian Arab Co. for Electronic Industries (Syronics) [88]

Technolab (Lebanon)[89]

Yona Star International (UAE, Syria) [90]

Zhou Yishan (Nationality: Chinese)[91]

Footnotes:

[1] Maksymilian Czuperski, et. al., “Distract, Deceive, Destroy: Putin at War in Russia,” Atlantic Council, April 2016, pp. 5, 19-20, available at http://publications.atlanticcouncil.org/distract-deceive-destroy/assets/download/ddd-report.pdf, accessed on January 25, 2018; Brennan Weiss, “This photo says it all about Russia’s involvement in Syria,” Business Insider, November 21, 2017, available at http://www.businessinsider.com/putin-hugs-assad-photo-syria-russia-2017-11, accessed on January 25, 2018; “Syria: Populations At Risk,” Press Release, Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, November 24, 2017, available at http://www.syriahr.com/en/?p=79314, accessed on December 11, 2017; “Syria envoy claims 400,000 have died in Syria conflict,” United Nations Radio, April 22, 2016, available at http://www.unmultimedia.org/radio/english/2016/04/syria-envoy-claims-400000-have-died-in-syria-conflict/#.WnnyOmnwaUn, accessed on February 6, 2018; “Syria – Events of 2016,” Human Rights Watch World Wide Web site, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2017/country-chapters/syria, accessed on February 6, 2018.

[2] “Allegations of Chemical Weapons Use in Syria Since 2012,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/170425_-_national_evaluation_annex_-_anglais_cle81722e.pdf, accessed on January 25, 2018.

[3] “Allegations of Chemical Weapons Use in Syria Since 2012,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/170425_-_national_evaluation_annex_-_anglais_cle81722e.pdf, accessed on January 25, 2018.

[4] “Government Assessment of the Syrian Government’s Use of Chemical Weapons on August 21, 2013,” Office of the Press Secretary, White House, August 30, 2013, available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/08/30/government-assessment-syrian-government-s-use-chemical-weapons-august-21, accessed on December 11, 2017; Amb. Samantha Power, “United States Mission to the United Nations Exit Memo,” United States Mission to the United Nations, January 5, 2017, available at https://2009-2017-usun.state.gov/remarks/7643, accessed on December 11, 2017.

[5] “National Evaluation: Chemical Attack of 4 April 2017 (Khan Sheikhoun) Clandestine Syrian Chemical Weapons Programme,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, April 25, 2017, p. 2, available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/170425_-_evaluation_nationale_-_anglais_-_final_1_cle8ca411.pdf, accessed on November 2, 2017; “Both ISIL and Syrian Government responsible for use of chemical weapons, UN Security Council told,” Press Release, United Nations, November 7, 2017, available at https://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=58051#, accessed on December 11, 2017.

[6] United Nations Security Council Draft Resolution, S/2017/172, February 28, 2017, p. 11, available at http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2017_172.pdf, accessed on December 4, 2017; “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed on December 14, 2017.

[7] “Autonomous Sanctions (Designated Persons and Entities and Declared Persons – Syria) List 2012,” Australian Department of Foreign Affairs, April 28, 2015, pp. 4, 18, available at https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2015C00369/Download, accessed on January 24, 2018; “Special Economic Measures (Syria) Regulations,” Canadian Minister of Justice, May 24, 2011, SOR/2011-114, p. 9, available at http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/SOR-2011-114.pdf, accessed on January 24, 2018; Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (Consolidated Version), September 27, 2017, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02012R0036-20170927&qid=1515531237694&from=EN, accessed on January 9, 2018; “Addition of Lists for the Measures to Freeze the Assets of President Bashar Al-Assad and His Related Individuals and Entities in Syria,” Press Release, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, December 22, 2011, available at http://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/announce/2011/12/1222_04.html, accessed on January 24, 2018; The Regulation on Special Measures Against Syria, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, September 2, 2011, available at https://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/forskrift/2014-02-14-214/*#* (in Norwegian), accessed on January 26, 2018; Amendment to Syria Sanctions – Consolidated List, State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), Government of Switzerland, October 10,, 2017, available at https://www.seco.admin.ch/dam/seco/de/…/Syrien/…/Syrien 2017-08-03.pdf, accessed on January 24, 2018; “Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control, January 26, 2018, p. 269, available at https://www.treasury.gov/ofac/downloads/sdnlist.pdf, accessed on January 26, 2018; “List of persons subject to financial sanctions under Article 2, paragraph 1, subparagraphs 15 to 19 of the Guidelines for Payment and Recognition for the Implementation of Duties such as International Peace and Security Maintenance,” South Korean Ministry of Strategy and Finance, December 11, 2017, available at http://www.mosf.go.kr/com/synap/synapView.do?atchFileId=ATCH_000000000006869&fileSn=2, accessed on February 7, 2018; “Guidelines for Payment and Receipt for the Fulfillment of Obligations such as International Peace and Security Maintenance,” Ministry of Strategy and Finance, August 12, 2016, available at http://www.mosf.go.kr/com/synap/synapView.do?atchFileId=ATCH_000000000002556&fileSn=1, accessed on February 7, 2018.

[8] United Nations Security Council Draft Resolution, S/2017/172, February 28, 2017, pp. 5, 9, 11, available at http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2017_172.pdf, accessed on February 8, 2018; “Russia, China block Security Council action on use of chemical weapons in Syria,” Press Release, United Nations, February 27, 2017, available at http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=56260#.WnyzgJ3waUk, accessed on February 8, 2018.

[9] “Implications of Soviet Use of Chemical and Toxic Weapons for U.S. Security Interests,” U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, September 15, 1983, p. 11, available at http://www.fas.org/irp/threat/cbw/sniecbw1983.pdf, accessed on September 17, 2013.

[10] Rene Backmann, “Chemical Weapons: Syrian Regime Has Developed its Arsenal with the Help of Several Countries,” Mediapart, June 2, 2017, available as EUL201706092761441 via Open Source Center (www.opensource.gov), accessed on December 1, 2017.

[11] “Australia Group: 2006 Information Exchange (IE),” U.S. Department of State, June 20, 2006, available at https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06PARIS4218_a.html, accessed on December 7, 2017.

[12] Bruce E. Bechtol Jr., “North Korea and Syria: Partners in Destruction and Violence,” Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, September 2015, pp. 282-283, available at https://blackboard.angelo.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/LFA/CSS/Course Material/SEC6317/readings/01_Bruce E. Bechtol.pdf, accessed on December 4, 2017.

[13] Nate Thayer, “North Korea and Syrian Chemical and Missile Programs,” NK News, June 19, 2013, available at https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:Iuw_Siobn3EJ:https://www.nknews.org/2013/06/north-korea-and-syrian-chemical-and-missile-programs/+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us, accessed via Google cache on January 8, 2018; Bruce E. Bechtol Jr., “North Korea and Syria: Partners in Destruction and Violence,” Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, September 2015, pp. 282-283, 286, available at https://blackboard.angelo.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/LFA/CSS/Course Material/SEC6317/readings/01_Bruce E. Bechtol.pdf, accessed on December 4, 2017.

[14] “N. Korea ‘Exporting Chemical Weapons Parts to Syria,’” Chosun Ilbo, June 17, 2013, available at http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2013/06/17/2013061700887.html, accessed on December 4, 2017.

[15] https://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFKBN1FM2NH

[16] Bruce E. Bechtol Jr., “North Korea and Syria: Partners in Destruction and Violence,” Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, September 2015, p. 283, available at https://blackboard.angelo.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/LFA/CSS/Course Material/SEC6317/readings/01_Bruce E. Bechtol.pdf, accessed on December 4, 2017.

[17] “Syria/Syrian chemical programme – National executive summary of declassified intelligence,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, September 3, 2013, pp. 1-2, available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/IMG/pdf/Syrian_Chemical_Programme.pdf, accessed on December 15, 2017.

[18] “National Evaluation: Chemical Attack of 4 April 2017 (Khan Sheikhoun) Clandestine Syrian Chemical Weapons Programme,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, April 25, 2017, p. 2, available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/170425_-_evaluation_nationale_-_anglais_-_final_1_cle8ca411.pdf, accessed on November 2, 2017; Rene Backmann, “Chemical Weapons: Syrian Regime Has Developed its Arsenal with the Help of Several Countries,” Mediapart, June 2, 2017, available as EUL201706092761441 via Open Source Center (www.opensource.gov), accessed on December 1, 2017.

[19] United Nations Security Council Draft Resolution, S/2017/172, February 28, 2017, p. 11, available at http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2017_172.pdf, accessed on December 4, 2017; “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed December 14, 2017; Robin Hughes, “SSRC: Spectre at the Table,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 22, 2014, available via Jane’s Information Group (www.janes.com), accessed on December 4, 2017.

[20] “Syria/Syrian chemical programme – National executive summary of declassified intelligence,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, September 3, 2013, pp. 1-3, available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/IMG/pdf/Syrian_Chemical_Programme.pdf, accessed on December 15, 2017; “Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR): Syria, Ballistic Missile Program,” U.S. Department of State, September 23, 2009, available at https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09STATE98667_a.html, accessed on December 7, 2017; “SSRC: Spectre at the Table,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 22, 2014, available via Jane’s Information Group (www.janes.com), accessed on December 4, 2017; Lucas Tomlinson, “Russia sends Syria its largest missile delivery to date, US officials say,” Fox News, February 8, 2017, available at http://www.foxnews.com/world/2017/02/08/russia-sends-syria-its-largest-missile-delivery-to-date-us-officials-say.html, accessed on February 8, 2018.

[21] “Missile Proliferation – Syria” Federation of American Scientists World Wide Web site, https://fas.org/irp/threat/missile/syria.htm, accessed on December 21, 2017; “SSRC: Spectre at the Table,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 22, 2014, available via Jane’s Information Group (www.janes.com), accessed on December 4, 2017; “Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat,” U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center, 2013, pp. 13, 17, available at https://fas.org/programs/ssp/nukes/nuclearweapons/NASIC2013_050813.pdf, accessed on December 30, 2017.

[22] “Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR): Syria, Ballistic Missile Program,” U.S. Department of State, September 23, 2009, available at https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09STATE98667_a.html, accessed on December 7, 2017; “SSRC: Spectre at the Table,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 22, 2014, available via Jane’s Information Group (www.janes.com), accessed on December 4, 2017; “Ballistic & Cruise Missile Threat,” NASIC-1031-0985-13, U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center, 2013, p. 13, available at https://fas.org/programs/ssp/nukes/nuclearweapons/NASIC2013_050813.pdf, accessed on December 30, 2016.

[23] “Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR): Syria, Ballistic Missile Program,” U.S. Department of State, September 23, 2009, available at https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09STATE98667_a.html, accessed on December 7, 2017.

[24] Bruce E. Bechtol Jr., “North Korea and Syria: Partners in Destruction and Violence,” Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, September 2015, p. 286, available at https://blackboard.angelo.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/LFA/CSS/Course Material/SEC6317/readings/01_Bruce E. Bechtol.pdf, accessed on December 4, 2017.

[25] “Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR): Syria, Ballistic Missile Program,” U.S. Department of State, September 23, 2009, available at https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09STATE98667_a.html, accessed on December 7, 2017; “SSRC: Spectre at the Table,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 22, 2014, available via Jane’s Information Group (www.janes.com), accessed on December 4, 2017; “Ballistic & Cruise Missile Threat,” NASIC-1031-0985-17, U.S, Defense Intelligence Ballistic Missile Analysis Committee, June 2017, p. 21, available at https://fas.org/irp/threat/missile/bm-2017.pdf, accessed on December 21, 2017.

[26] Robin Hughes, “SSRC: Spectre at the Table,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 22, 2014, available via Jane’s Information Group (www.janes.com), accessed on December 4, 2017.

[27] Lucas Tomlinson, “Russia sends Syria its largest missile delivery to date, US officials say,” Fox News, February 8, 2017, available at http://www.foxnews.com/world/2017/02/08/russia-sends-syria-its-largest-missile-delivery-to-date-us-officials-say.html, accessed on February 8, 2018; “Syria/Syrian chemical programme – National executive summary of declassified intelligence,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, September 3, 2013, pp. 1-3, available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/IMG/pdf/Syrian_Chemical_Programme.pdf, accessed on December 15, 2017.

[28] Rene Backmann, “How Bashir Al-Asad Gassed His Own People: Secret Plans and Proof,” Mediapart, June 1, 2017, available as EUL2017060928105207 via Open Source Center (www.opensource.gov), accessed on January 1, 2018.

[29] Shashank Bengali, “Syrian leader discloses locations of dozens of chemical weapons sites,” Los Angeles Times, September 24, 2013, available at http://www.latimes.com/world/la-fg-syria-chemical-20130925-story.html, accessed on November 13, 2017; Adam Entous, Julian E. Barnes, and Nour Malas, “Elite Syrian Unit Scatters Chemical Arms Stockpile,” Wall Street Journal, September 12, 2013, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/elitesyrian-unit-scatters-chemical-arms-stockpile-1379036397?tesla=y, accessed on November 13, 2017.

[30] “Allegations of Chemical Weapons Use in Syria Since 2012,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/170425_-_national_evaluation_annex_-_anglais_cle81722e.pdf, accessed on January 25, 2018.

[31] “Government Assessment of the Syrian Government’s Use of Chemical Weapons on August 21, 2013,” Office of the Press Secretary, White House, August 30, 2013, available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/08/30/government-assessment-syriangovernment-s-use-chemical-weapons-august-21, accessed on December 11, 2017; Gregory Koblentz, “Syria’s Chemical Weapons Kill Chain,” Foreign Policy, April 7, 2017, available at http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/04/07/syrias-chemical-weapons-kill-chain-assad-sarin/, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[32] United Nations Security Council Resolution 2118 (2013), September 23, 2013 pp. 5-7.

[33] “OPCW Maritime Operation Completes Deliveries of Syrian Chemicals to Commercial Destruction Facilities,” Press Release, Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, July 24, 2014, available at https://www.opcw.org/news/article/opcw-maritime-operation-completes-deliveries-of-syrian-chemicals-to-commercial-destruction-facilitie/, accessed on January 4, 2018.

[34] “Progress in the Elimination of the Syrian Chemical Weapons Programme,” Note by the Director-General, Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, October 23, 2017, available at https://www.opcw.org/fileadmin/OPCW/EC/87/en/ec87dg02_e_.pdf, accessed on January 4, 2018.

[35] Anthony Deutsch, “Exclusive – Weapons Inspectors Find Undeclared Sarin and VX Traces in Syria: Diplomats,” Reuters, May 8, 2015, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-chemicals-exclus/exclusive-weapons-inspectors-find-undeclared-sarin-and-vx-traces-in-syria-diplomats-idU.S.KBN0NT1YR20150508, accessed on May 22, 2015.

[36] Adam Entous and Naftali Bendavid, “Mission to Purge Syria of Chemical Weapons Comes Up Short,” Wall Street Journal, July 23, 2015, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/mission-to-purge-syria-of-chemical-weapons-comes-up-short-1437687744, accessed on July 28, 2015.

[37] “Progress in the Elimination of the Syrian Chemical Weapons Programme,” Note by the Director-General, Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, October 23, 2017, available at https://www.opcw.org/fileadmin/OPCW/EC/87/en/ec87dg02_e_.pdf, accessed on January 4, 2018.

[38] “National Evaluation: Chemical Attack of 4 April 2017 (Khan Sheikhoun) Clandestine Syrian Chemical Weapons Programme,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, April 25, 2017, p. 5, available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/170425_-_evaluation_nationale_-_anglais_-_final_1_cle8ca411.pdf, accessed on November 2, 2017; Daniel R. Coats, Director of National Intelligence, “Worldwide Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” May 11, 2017, p. 7, available at https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Testimonies/SSCI Unclassified SFR – Final.pdf, accessed on December 7, 2017.

[39] Rene Backmann, “Chemical Weapons: Syrian Regime Has Developed its Arsenal with the Help of Several Countries,” Mediapart, June 2, 2017, available as EUL201706092761441 via Open Source Center (www.opensource.gov), accessed on December 1, 2017.

[40] “Syria government ‘producing chemical weapons at research facilities’,” BBC News, May 4, 2017, available at http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-39796763, accessed on November 2, 2017; “OPCW Executive Council Adopts Decision Regarding the OPCW-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism Reports About Chemical Weapons Use in the Syrian Arab Republic,” Press Release, Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, November 11, 2016, available at https://www.opcw.org/news/article/opcw-executive-council-adopts-decision-regarding-the-opcw-united-nations-joint-investigative-mechanism-reports-about-chemical-weapons-use-in-the-syrian-arab-republic/, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[41] “Three Possible Reasons for the Attack on Syria’s Jamraya Facility,” YNet News, February 7, 2018, available at https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-5096766,00.html, accessed on February 7, 2018; ‘”Israeli Jets Hit Syria’s Masyaf Chemical Site’ – Reports,” BBC News, September 7, 2017, available at http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-41184867, accessed on February 7, 2018.

[42] “National Evaluation: Chemical Attack of 4 April 2017 (Khan Sheikhoun) Clandestine Syrian Chemical Weapons Programme,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, April 25, 2017, pp. 2, 4, available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/170425_-_evaluation_nationale_-_anglais_-_final_1_cle8ca411.pdf, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[43] “Seventh Report of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism,” United Nations, S/2017/904, October 26, 2017, pp. 32-33, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2017/904, accessed on January 9, 2018.

[44] “Rescuers, doctors in Syria’s rebel-held Idlib says chemical gas used,” Reuters, February 5, 2018, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-attack/rescuers-doctors-in-syrias-rebel-held-idlib-says-chemical-gas-used-idUSKBN1FP27K, accessed on February 8, 2018.

[45] “Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/1327 of 17 July 2017 implementing Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria,” Official Journal of the European Union, L 185/22-23, July 18, 2017, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32017R1327, accessed on January 23, 2018; “Third report of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism,” United Nations, S/2016/738, August 24, 2016, pp. 4,8,11, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2016/738, accessed on January 10, 2018; “Fourth report of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism,” United Nations, S/2016/888, October 21, 2016, p. 8, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2016/888, accessed on February 8, 2018; “Syria: Witness testimony reveals details of illegal chemical attack on Saraqeb,” Press Release, Amnesty International, February 6, 2018, available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2018/02/syria-witness-testimony-reveals-details-of-illegal-chemical-attack-on-saraqeb/, accessed on February 8, 2018.

[46] “SSRC: Spectre at the Table,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 22, 2014, available via Jane’s Information Group (www.janes.com), accessed on December 4, 2017; Rene Backmann, “How Bashir Al-Asad Gassed His Own People: Secret Plans and Proof,” Mediapart, June 1, 2017, available as EUL2017060928105207 via Open Source Center (www.opensource.gov), accessed on January 1, 2018; Adam Entous, Julian E. Barnes, and Nour Malas, “Elite Syrian Unit Scatters Chemical Arms Stockpile,” Wall Street Journal, September 12, 2013, available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/elitesyrian-unit-scatters-chemical-arms-stockpile-1379036397?tesla=y, accessed on November 13, 2017.

[47] “Treasury Sanctions Additional Individuals and Entities in Response to Continuing Violence in Syria,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, December 23, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0690.aspx, accessed on November 2, 2017; United Nations Security Council Draft Resolution, S/2017/172, February 28, 2017, pp. 5, 9, 12, available at http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2017_172.pdf, accessed on February 8, 2018; “Russia, China block Security Council action on use of chemical weapons in Syria,” Press Release, United Nations, February 27, 2017, available at http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=56260#.WnyzgJ3waUk, accessed on February 8, 2018.

[48] “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed on December 14, 2017.

[49] Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009), United Nations, S/2012/422, June 14, 2012, p. 24, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2012/422, accessed on December 4, 2017.

[50] Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009), United Nations, S/2012/422, June 14, 2012, pp. 27-29, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2012/422, accessed on December 4, 2017; “Report of the Panel of Experts Established Pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2010/571, November 5, 2010, pp. 25-26, available at http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3 CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/DPRK%20S%202010%20571%20PoE%20Report.pdf, accessed on January 10, 2018.

[51] Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009), United Nations, S/2013/337, June 11, 2013, pp. 36-37, 103, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2013/337, accessed on December 4, 2017.

[52] “Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1874 (2009),” United Nations, S/2016/157, February 26, 2016, pp. 29-30, available at http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2016_157.pdf, accessed on December 4, 2017.

[53] “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed on December 14, 2017.

[54] “Shield S04B-08: Syria Arranging to Acquire CW Equipment from Two Indian Companies,” U.S. Department of State, December 30, 2008, available at https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08STATE135048_a.html, accessed on December 22, 2017; “Shield S04D-08: Preventing Indian Firms from Circumventing Export Controls,” U.S. Department of State, February 27, 2009, available at https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09STATE18867_a.html, accessed on January 8, 2018.

[55] “National Evaluation: Chemical Attack of 4 April 2017 (Khan Sheikhoun) Clandestine Syrian Chemical Weapons Programme,” Directorate-General of External Security, Government of France, April 25, 2017, p. 5, available at http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/170425_-_evaluation_nationale_-_anglais_-_final_1_cle8ca411.pdf, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[56] “Treasury Sanctions 271 Syrian Scientific Studies and Research Center Staff in Response to Sarin Attack on Khan Sheikhoun,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, April 24, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/sm0056.aspx, accessed on February 8, 2018.

[57] Joint Press Release from Mr. Le Drian and Le Marie, Ministry of European and Foreign Affairs, January 23, 2018, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018.

[58] “SSRC: Spectre at the Table,” Jane’s Defense Weekly, January 22, 2014, available via Jane’s Information Group (www.janes.com), accessed on December 4, 2017.

[59] “Center for Scientific Studies and Research – Procurement Notices,” dgMarket World Wide Web site, https://www.dgmarket.com/tenders/adminShowBuyer.do?buyerId=7217705, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[60] Tender No: 141 200, June 3, 2017, available at https://www.dgmarket.com/tender/15697352, accessed on November 10, 2017.

[61] Notice/Contract No: 141782, July 31, 2017, available at http://d.infostores.biz/T41274886.html?id=a2RvEGUvIBo1JHxTBEUWLVoyfjsbFDogVRQENA, accessed on November 3, 2017; “Metal Manufacturing Plant list of Tenders – Procurement Notices,” dgMarket World Wide Web site, https://www.dgmarket.com/tenders/adminShowBuyer.do?buyerId=7126104, accessed on January 22, 2018; “Counter Terrorism Designations; Non-proliferation Designation; Counter Narcotics Designations Removals and Update; Kingpin Act Designations Removals and Update,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), February 23, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20170223.aspx, accessed on January 29, 2018; “Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) Annex Handbook 2017,” p. 116, available at http://mtcr.info/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/MTCR-Handbook-2017-INDEXED-FINAL-Digital.pdf, accessed on January 10, 2018; “Ammonium Nitrate – PubChem Compound Database,” National Center for Biotechnology Information, available at https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/ammonium_nitrate#section=Top, accessed on January 10, 2018; Ammonium Nitrate Factsheet, the Fertilizer Institute, available at https://www.tfi.org/sites/default/files/documents/ammoniumnitrateinfographic.pdf, accessed on January 10, 2018.

[62] Tender No: 141 005, May 14, 2017, available at https://www.dgmarket.com/tender/15482485, accessed on November 3, 2017.

[63] Bid No. 141748, July 23, 2017, available at http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:CC7DVzfLb4QJ:www.elan.gov.sy/2017/site/arabic/index.php%3Fnode%3D343%26Last%3D13010%26CurrentPage%3D1280%26First%3D1271%26RID%3D-1%26Vld%3D%26Cat%3D%26City%3D%26Loc1%3D%26Key1%3D%26SDate%3D%26EDate%3D%26Year%3D%26or%3D%26Country%3D%26Num%3D%26Dep%3D-1%26+&cd=9&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us, accessed on November 27, 2017; Tender No: 141596, July 11, 2017, available at https://www.dgmarket.com/tender/15967699 (in Arabic), accessed on November 3, 2017; Tender No: 141541, June 23, 2017, available at https://www.dgmarket.com/tender/15837672, accessed on November 3, 2017; Tender No: 141781, 7458 / p, July 31, 2017, available at https://www.dgmarket.com/tender/16252700, accessed on November 3, 2017; Tender No. 7461/m, November 22, 2017, available at http://d.infostores.biz/T430041337.html?id=bGM1SjJ6dU0/KSoFDkZCcgpnJXlOBzk/UgoENRcS, accessed on January 22, 2018; “Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) Annex Handbook 2017,” pp.ix, 49, 51-52, 93, 100, 112, 156, 177, 182, 255, 280, 346, available at http://mtcr.info/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/MTCR-Handbook-2017-INDEXED-FINAL-Digital.pdf, accessed on January 10, 2018.

[64] Tender No. me:12083467, February 9, 2014, available at http://www.dgmarket.com/tenders/np-notice.do?noticeId=10583327, accessed on March 30, 2017.

[65] “Treasury Sanctions Networks Providing Support to the Government of Syria,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 21, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0526.aspx, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[66] “In Hindsight: The Demise of the JIM,” UN Security Council, December 28, 2017, available at http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2018-01/in_hindsight_the_demise_of_the_jim.php, accessed on February 7, 2018; “Security Council Considers Fourth Report by Joint Investigative Mechanism,” Press Release, United Nations, October 27, 2016, available at https://www.un.org/press/en/2016/dc3668.doc.htm, accessed on February 8, 2018; “Joint Investigative Mechanism Report on Khan Shaykhun and Um Housh,” Press Release, U.S. State Department, October 27, 2017, available at https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2017/10/275166.htm, accessed on February 7, 2018; “Seventh Report of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism,” United Nations, S/2017/904, October 26, 2017, pp. 3, 32-33, available at http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2017/904, accessed on January 9, 2018.

[67] https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018

[68] International Partnership Against Impunity for the Use of Chemical Weapons, available at https://www.noimpunitychemicalweapons.org/-en-.html#wrapper, accessed on January 23, 2018.

[69] Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 and Following of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018; Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018;

[70] “Treasury Sanctions Additional Individuals and Entities in Response to Continuing Violence in Syria,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, December 23, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0690.aspx, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[71] Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (Consolidated Version), September 27, 2017, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02012R0036-20170927&qid=1515531237694&from=EN, accessed on January 9, 2018; “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed on December 14, 2017.

[72] Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 and Following of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018; Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018.

[73] “Treasury Targets Syrian Regime Financial and Weapons Networks,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, March 31, 2015, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/JL10013.aspx , accessed on January 9, 2018.

[74] Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 and Following of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018; Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018.

[75] Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (Consolidated Version), September 27, 2017, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02012R0036-20170927&qid=1515531237694&from=EN, accessed on January 9, 2018; “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed on December 14, 2017.

[76] Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 and Following of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018; Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018.

[77] Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (Consolidated Version), September 27, 2017, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02012R0036-20170927&qid=1515531237694&from=EN, accessed on January 9, 2018; “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed on December 14, 2017.

[78] Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 and Following of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018; Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018.

[79] “Treasury Sanctions Networks Providing Support to the Government of Syria,” Press Center, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 21, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/presscenter/press-releases/Pages/jl0526.aspx, accessed on November 2, 2017; “Syria Designations; Non-proliferation Designations,” Office of Foreign Assets Control, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 21, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20160721.aspx, accessed on February 6, 2018.

[80] Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (Consolidated Version), September 27, 2017, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02012R0036-20170927&qid=1515531237694&from=EN, accessed on January 9, 2018; “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed on December 14, 2017.

[81] “Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1117/2012 of 29 November 2012 implementing Article 32(1) of Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria,” Official Journal of the European Union, November 30, 2012, L330/10-11, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2012:330:0009:0011:EN:PDF, accessed on January 24, 2018.

[82] “Treasury Sanctions Senior Al-Nusrah Front Leaders Concurrently with UN Designations,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, February 23, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/sm0011.aspx, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[83] Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 and Following of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018; Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018.

[84] “Non-proliferation Designations; Syria Designations; Zimbabwe Designations Removals,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), January 12, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20170112.aspx, accessed on January 29, 2018.

[85] “Treasury Sanctions Networks Providing Support to the Government of Syria,” Press Center, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 21, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/presscenter/press-releases/Pages/jl0526.aspx, accessed on November 2, 2017; “Syria Designations; Non-proliferation Designations,” Office of Foreign Assets Control, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 21, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20160721.aspx, accessed on February 6, 2018.

[86] “Treasury Targets Syrian Regime Financial and Weapons Networks,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, March 31, 2015, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/JL10013.aspx , accessed on January 9, 2018.

[87] Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 and Following of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018; Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018;

[88] Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (Consolidated Version), September 27, 2017, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02012R0036-20170927&qid=1515531237694&from=EN, accessed on January 9, 2018; “Fact Sheet: Increasing Sanctions Against Syria,” Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 18, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Documents/Fact%20Sheet.pdf, accessed on December 14, 2017.

[89] “Treasury Sanctions Additional Individuals and Entities in Response to Continuing Violence in Syria,” Press Release, U.S. Department of the Treasury, December 23, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0690.aspx, accessed on November 2, 2017.

[90] “Treasury Sanctions Networks Providing Support to the Government of Syria,” Press Center, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 21, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/presscenter/press-releases/Pages/jl0526.aspx, accessed on November 2, 2017; “Syria Designations; Non-proliferation Designations,” Office of Foreign Assets Control, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 21, 2016, available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20160721.aspx, accessed on February 6, 2018.

[91] Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 and Following of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018; Order of January 18, 2018 Implementing Articles L.562-3 of the Monetary and Financial Code, French Ministry of Economy and Finances, available at https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/desarmement-et-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-au-desarmement-et-a-la-non-proliferation/evenements-lies-aux-armes-chimiques/article/communique-de-presse-conjoint-de-mm-le-drian-et-le-maire-23-janvier-2018# (in French), accessed on January 23, 2018.