In response to China’s military modernization over the past few decades, the U.S. government has developed a range of sanctions and regulatory tools to target the Chinese defense industry and limit the ways U.S. resources, technology, and products contribute to the growth of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). These efforts accelerated during the Trump Administration with the expansion of military end user-based export controls to China, the creation of the Military End User List, and the advent of investment restrictions on Chinese military-related companies.

This report provides an overview of the policies and programs driving Chinese defense industry modernization, the key entities in China implementing these policies over time, and the strategic trade and investment restrictions that the U.S. government has developed in response. This response targets the Chinese military-industrial complex as a whole, as well as the specific entities that operate within it.

Over the past year, the U.S. government published several lists of “Chinese military companies” as part of its strategy to target the Chinese defense industry. These lists identify Chinese state-owned and private companies with links to the Chinese military and, in some cases, apply restrictions on trade with and investment in these companies. More broadly, these lists reflect an effort by the United States to limit support to any entity in China that supports the military.

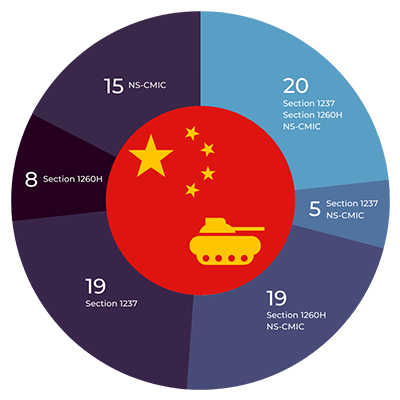

The Appendix to this report contains a searchable table naming each entity that appears on the lists that exclusively target China’s military, including its Chinese name (when available), background information, and the list(s) on which it appears. The table illustrates the diverse types of entities named on these lists, from aerospace, to telecommunications, to energy firms. While the listing criteria for these lists is similar, only 20 of the combined total of 86 entities appear on every list. This divergence highlights the difficulty government and private actors face in determining a Chinese company’s military ties in the era of Military-Civil Fusion.

Overview of Chinese Defense Industry Policies and Programs

The Growth of the Chinese Defense Industry During the Reform Era

U.S. strategic trade and investment regulations target a Chinese defense industrial base that has experienced forty years of growth and reform. During the Mao era, the Chinese defense industry consisted of numbered “machine-building industry” ministries (机械工业部), with each ministry responsible for a certain sector of defense production, such as aerospace, aviation, nuclear weapons, and shipbuilding.[1] While some of China’s strategic weapons programs achieved success, such as the “Two Bombs, One Satellite” initiative, many fell behind schedule or failed due to technical limitations or competing political priorities.[2]

This dynamic began to change during the 1980s and 1990s. The Chinese government lost confidence in the country’s defense industrial system after China’s poor performance in the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War and U.S. displays of military superiority in the 1991 Gulf War and the 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis.[3] After a series of ineffective organizational changes between 1982 and 1993, the government converted its defense industry ministries into five state-owned enterprises (SOEs), each responsible for a sector of the defense industry. The aim was to enhance innovation across the defense industry and decrease its reliance on Chinese government support.[4] In 1999, in a further effort to modernize the industry, the government split these five SOEs into ten group companies (集团公司), with each company overseeing a network of subsidiaries and research institutes.[5]

This dynamic began to change during the 1980s and 1990s. The Chinese government lost confidence in the country’s defense industrial system after China’s poor performance in the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War and U.S. displays of military superiority in the 1991 Gulf War and the 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis.[3] After a series of ineffective organizational changes between 1982 and 1993, the government converted its defense industry ministries into five state-owned enterprises (SOEs), each responsible for a sector of the defense industry. The aim was to enhance innovation across the defense industry and decrease its reliance on Chinese government support.[4] In 1999, in a further effort to modernize the industry, the government split these five SOEs into ten group companies (集团公司), with each company overseeing a network of subsidiaries and research institutes.[5]

Around the same time, the Chinese government reformed the defense acquisition process to increase efficiency and introduce stronger quality control oversight.[6] Specifically, the government separated the management of defense industry SOEs from the defense acquisition process. A re-organized Committee on Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense (COSTIND), under the civilian State Council, oversaw and regulated the defense industry. The General Armaments Department (GAD), under the Central Military Commission,[7] managed PLA procurement. Many SOE production subsidiaries not involved in defense-related work were sold off or released into the private sector, leaving the SOEs and their remaining subsidiaries to focus on research, development, and production with defense applications.[8] Defense SOEs were also allowed to sell securities on Chinese stock exchanges, enabling them to raise outside capital.[9]

These reforms gradually introduced profit and efficiency into China’s defense industry, with group companies and their subsidiaries given more operational autonomy. Beginning in the early 2000s, the defense industry focused on “spin-on” (民转军) technologies, which are technologies developed for civilian applications that are then converted for military uses. This allowed Chinese companies to obtain foreign technology and know-how for civilian activities that could ultimately benefit their defense-related business.[10]

At the same time, Chinese defense supply opportunities began opening to some private firms. While traditional defense-heavy sectors like shipbuilding and armaments remained dominated by SOEs, private companies in commercially-driven sectors like information and communication technology (ICT) began selling to the PLA. This gave rise to a new generation of private ICT firms – some of which had ties to the government – that supplied the PLA, such as Huawei Technologies.[11]

Chinese firms also benefited from government-funded advancements in national science and technology research capabilities. In the late 1980s, the Chinese government increased its funding of strategic technology and defense-related programs at universities and research institutions.[12] For example, the 863 Program funded high-tech research projects at universities in fields such as aerospace, automation, and information technology.[13] COSTIND similarly funded defense disciplines and research laboratories at major Chinese universities through “joint construction” agreements.[14] The Chinese government also used scholarship and grant programs to recruit scientists from overseas and to train a new generation of national technical experts.[15] Combined, these efforts provided Chinese defense firms with a stronger science and technology base from which to draw for the development of advanced military capabilities.

The Defense Industry and Defense Industrial Policy in the Xi-era

As a result of these reforms and as China’s defense budget increased throughout the 2000s and 2010s, Chinese companies were better able to meet PLA procurement needs. These companies also became commercially successful, with annual revenue for China’s big 10 defense industrial SOEs reportedly skyrocketing from 15 billion RMB ($2.3 billion) in 2004 to 120 billion RMB ($18.6 billion) in 2015.[16] To build on these successes, the Xi Jinping administration has implemented industrial policies aimed at supporting strategic and emerging high-tech industries, such as Military-Civil Fusion (MCF), Made in China 2025, the Strategic Emerging Industries Plan, and the Innovation-Driven Development Strategy.

MCF is the policy most directly tied to harnessing the power of civilian development and innovation to the service of China’s defense industrial base.[17] In 2015, Xi announced MCF as a national-level priority, and in 2017 he established the Commission for Integrated Civilian-Military Development, an inter-agency body chaired by Xi to oversee government implementation of MCF plans.[18] A primary aim of China’s MCF strategy is to provide the Chinese military with an arsenal of domestic suppliers of high-tech and dual-use equipment. These firms also act as research partners for the Chinese military and defense industry SOEs.

Chinese defense SOEs are still expected to develop commercially marketable goods and technology themselves, which provides them with a steady revenue stream. According to a report by the National Defense University, about half of the Chinese defense industry’s revenue comes from civilian business, and in certain sectors, such as the ordnance and nuclear sectors, it may be as high as 80 or 90 percent.[19]

China has also continued to reform and reorganize the government agencies that manage the defense industry. In 2008, the government formed the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), which is responsible for managing industrial planning and policy and promotes the development of communication technology and information security.[20] MIIT oversees the State Administration for Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND), which was created at the same time from the reorganization of COSTIND.[21]

SASTIND issues and implements policies, regulations, and standards for China’s defense industry on behalf of MIIT.[22] As part of this responsibility, SASTIND oversees MCF and coordinates MCF efforts among government agencies, SOEs, private companies, universities, and local governments.[23] It also coordinates military production projects that involve cooperation between SOEs and funds the development of military technology education and research programs at Chinese universities.[24] Under Xi, SASTIND directors often are promoted to be provincial party secretaries and governors, a sign both of the importance of the agency and a factor enhancing local government participation in MCF and related programs.[25]

Xi also reformed the military defense industrial system as part of the government’s 2015 PLA reforms. The Equipment Development Department (EDD) was created to replace GAD in managing military acquisition, procurement, and R&D responsibilities on behalf of the Central Military Commission (CMC). EDD carries out these responsibilities in conjunction with service-level equipment departments[26] and is subject to more stringent oversight than its predecessor.[27] This reform appears aimed at improving oversight of defense procurement and reducing inefficient defense acquisitions.[28]

The 2015 PLA reforms also elevated the CMC’s Science and Technology Commission (STC) from its previous position under GAD to a department-level role, on equal footing with EDD.[29] The STC reportedly guides weapons and equipment development, and it consists of sub-committees composed of civilian experts that advise the CMC on technological progress.[30] It reportedly hosts a defense innovation division modeled on the U.S. Defense Department’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and it also plays a role in facilitating MCF.[31]

Despite these advances, China’s defense industry continues to rely on foreign technology. According to a recent RAND Corporation report, China’s domestic firms lag in several key military capabilities, including semiconductor production equipment, aircraft engine construction, and submarine technology.[32] As the Chinese government increases funding for domestic production of these technologies, it persistently relies on foreign acquisition and joint ventures. Recent U.S. strategic trade and investment controls aim to limit such acquisition in an effort to slow the qualitative rise of China’s military.

U.S. Policies, Regulations, and Sanctions Targeting the Chinese Defense Industry

Restrictions on Dual-Use Exports to China

The U.S. Export Administration Regulations (EAR) and the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) restrict the export of military-related and dual-use items, including to China. Items subject to the EAR or that appear on the U.S. Munitions List under ITAR likely require a license for export to China and, as of July 2020, to Hong Kong as well.[33]

In addition, since 1997, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) has maintained the Entity List, which identifies entities subject to heightened license requirements for the export of items controlled by the EAR. The Entity List targets companies, organizations, and individuals involved in weapons of mass destruction-related proliferation or that are determined to be acting contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.[34] The Chinese Academy of Engineering Physics (CAEP), which is responsible for the research, development, and testing of China’s nuclear weapons, was among the first entities added to this list.[35] Today, dozens of Chinese SOEs, research institutions, universities, and companies appear on the Entity List for supporting the PLA and its modernization.[36]

In 2007, BIS amended the EAR to require licenses for exports of certain dual-use items to China, if the items were intended for military end use, which BIS defined as the “incorporation into . . . or for the use, development, or production of military items” described on the U.S. Munitions List, the Wassenaar Arrangement’s Munitions List, or certain military-related items subject to the EAR. These items would otherwise not require licenses.[37] In April 2020, BIS broadened the definition of military end use to include any activity that “supports or contributes to the operation, installation, maintenance, repair, overhaul, refurbishing, development, or production of military items” described on the U.S. Munitions List or for certain military-related items subject to the EAR.[38] BIS also began restricting the export of certain items to military end users in China, which it had previously restricted for Russia and Venezuela in 2014.[39]

The reform and reorganization of China’s defense sector described above has complicated efforts to identify military end users in China. In an effort to help U.S. exporters do so, particularly in the face of increasing trade restrictions on that sector, BIS created the Military End User List (MEU List) in December 2020. This list names entities based in China (and Russia) that BIS considers to be military end users, as described above.[40] Importantly, the MEU List is not exhaustive; entities not listed may still be subject to military end use and military end user restrictions.[41] Seventy-one of the 115 entities currently on the MEU List are based in China.[42] These entities are predominantly focused in China’s aerospace and aviation sectors and include subsidiaries of large SOEs.[43]

Restrictions on Investment by U.S. Persons

In late 2020, the United States created new restrictions on U.S. investment in entities tied to China’s defense industry in order to limit the ways U.S. capital finances the growth of these entities. On November 12, 2020, President Trump issued Executive Order 13959, which prohibited U.S. persons from engaging in transactions in publicly traded securities of entities determined by the Defense Department to be “Communist Chinese military companies” operating in the United States under Section 1237 of the U.S. National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 1999.[44] The Defense Department had released an initial list of Chinese companies that were determined to meet the criteria established in Section 1237 on June 12, 2020 and added additional companies on August 28 and December 3, 2020, and January 14, 2021.[45]

An entity qualifies as a “Communist Chinese military company” under Section 1237 if it operates in the United States and is:

- Owned or controlled by, or affiliated with, the PLA, which includes the land, naval, and air military services, the police, and China’s intelligence services, or a Chinese government ministry; or

- Owned or controlled by an entity affiliated with the defense industrial base of China; and

- Engaged in providing commercial services, manufacturing, producing, or exporting.[46]

On June 3, 2021, the Biden Administration reissued these investment restrictions through Executive Order 14032, which amended Executive Order 13959 and expanded the listing criteria to include Chinese entities operating in the surveillance technology sector.[47] To implement this order, the Treasury Department created the Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List (NS-CMIC List). Restrictions on these entities entered into force on August 2, 2021. U.S. persons are prohibited from engaging in transactions in publicly traded securities of any company that appears on the NS-CMIC List, following a one-year wind-down period.[48]

An entity qualifies for inclusion on the NS-CMIC List if it:

- Operates or has operated in the defense and related materiel sector or the surveillance technology sector in China; or

- Owns or controls, or is owned or controlled by, directly or indirectly, a person who operates in the sectors mentioned above.[49]

Separately, the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021 established an additional tool for identifying Chinese military companies operating in the United States. Section 1260H requires the Defense Department to publish a list of “Chinese military companies” operating in the United States. In June 2021, the Defense Department published a list of companies identified under Section 1260H[50] and vacated the Section 1237 list.[51] Unlike the NS-CMIC List, there are no restrictions on entities identified under Section 1260H.[52]

An entity qualifies as a “Chinese military company” under Section 1260H if it operates in the United States and is:

- Directly or indirectly owned, controlled, or beneficially owned by the PLA or any other organization subordinate to China’s Central Military Commission; or

- Engaged, officially or unofficially, as an agent of the PLA or any other organization subordinate to China’s Central Military Commission; or

- Identified as a Military-Civil Fusion contributor; and

- Engaged in providing commercial services, manufacturing, producing, or exporting.[53]

Section 1260H of the 2021 NDAA defines Military-Civil Fusion (MCF) contributors as:

- Entities receiving assistance from the Chinese government through science and technology efforts initiated under the Chinese military industrial planning apparatus;

- Entities affiliated with MIIT, including through research partnerships and projects;

- Entities receiving assistance, operational direction, or policy guidance from SASTIND;

- Entities or subsidiaries defined as “defense enterprises” by China’s State Council;

- Entities residing in or affiliated with an MCF enterprise zone or receiving assistance from the Chinese government through such an enterprise zone;

- Entities awarded military production licenses; or

- Entities that advertise on national, provincial, and non-governmental military equipment procurement platforms in China.[54]

Appendix: Chinese Military Companies Identified by the United States

The following table provides information on Chinese military companies operating in the United States that have been identified on the Section 1260H or NS-CMIC lists, as well as the Section 1237 list, which was vacated following the publication of the other lists. The table notes when an entity is also included on the MEU List but does not list all Chinese entities that appear on that list because it is not China-specific. The MEU List also includes military end users in Russia and the authority to designate such end users in Burma and Venezuela.

The information in this table is based on open sources, including company websites, annual financial reports, state-owned media articles, and government documents. Of the 86 companies identified:

- 20 appear on the Section 1237, Section 1260H, and NS-CMIC lists

- 5 only appear on the Section 1237 and NS-CMIC lists

- 19 only appear on the Section 1260H and NS-CMIC lists

- 19 only appear on the Section 1237 list

- 8 only appear on the Section 1260H list

- 15 only appear on the Section NS-CMIC list

| Name | Description | List(s) |

|---|---|---|

Advanced Micro-Fabrication Equipment Inc. (AMEC) |

| Section 1237 |

Aero Engine Corporation of China (AECC) |

| Section 1237 |

Aerospace CH UAV Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

Aerospace Communications Holdings Group Company Limited (Aerocom) |

| NS-CMIC |

Aerosun Corporation |

| Section 1260H |

Anhui Greatwall Military Industry Company Limited |

| NS-CMIC |

Aviation Industry Corporation of China, Ltd. (AVIC) |

| Section 1237 |

AVIC Aviation High-Technology Company Limited |

| Section 1260H |

AVIC Heavy Machinery Company Limited |

| Section 1260H |

AVIC Jonhon Optronic Technology Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

AVIC Shenyang Aircraft Company Limited |

| Section 1260H |

AVIC Xi'an Aircraft Industry Group Company Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

Beijing Zhongguancun Development Investment Center |

| Section 1237 |

Changsha Jingjia Microelectronics Company Limited |

| NS-CMIC |

China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT) |

| Section 1237 |

China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation Limited (CASIC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Aerospace Times Electronics Co., Ltd. (CATEC) |

| NS-CMIC |

China Avionics Systems Company Limited |

| NS-CMIC |

China Communications Construction Company Limited (CCCC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Communications Construction Group (Limited) |

| Section 1260H |

China Construction Technology Co. Ltd. (CCTC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Electronics Corporation (CEC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC) |

| Section 1237 |

China General Nuclear Power Corporation (CGN) |

| Section 1237 |

China International Engineering Consulting Corp. (CIECC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Marine Information Electronics Company Limited |

| Section 1260H |

China Mobile Communications Group Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1237 |

China Mobile Limited |

| Section 1260H |

China National Aviation Holding Co. Ltd. (CNAH) |

| Section 1237 |

China National Chemical Corporation (ChemChina) |

| Section 1237 |

China National Chemical Engineering Group Co., Ltd. (CNCEC) |

| Section 1237 |

China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) |

| Section 1237 |

China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) |

| Section 1237 |

China North Industries Group Corporation Limited (Norinco Group) |

| Section 1237 |

China Nuclear Engineering Corporation Limited (CNEC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Railway Construction Corporation Limited (CRCC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Satellite Communications Co., Ltd. |

| NS-CMIC |

China Shipbuilding Industry Company Limited (CSICL) |

| NS-CMIC |

China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation (CSIC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Shipbuilding Industry Group Power Company Limited (CSICP) |

| NS-CMIC |

China South Industries Group Corporation (CSGC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Spacesat Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1237 |

China State Construction Group Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1237 |

China State Shipbuilding Corporation Limited (CSSC) |

| Section 1237 |

China Telecom Corporation Limited |

| Section 1260H |

China Telecommunications Corporation |

| Section 1237 |

China Three Gorges Corporation Limited |

| Section 1237 |

China Unicom (Hong Kong) Limited |

| Section 1260H |

China United Network Communications Group Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1237 |

CNOOC Limited |

| Section 1260H |

Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China, Ltd. (COMAC) |

| Section 1237 |

Costar Group Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

CRRC Corp. |

| Section 1237 |

CSSC Offshore & Marine Engineering (Group) Company Limited (COMEC) |

| NS-CMIC |

Dawning Information Industry Co. (Sugon) |

| Section 1237 |

Fujian Torch Electron Technology Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

Global Tone Communication Technology Co. Ltd. (GTCOM) |

| Section 1237 |

GOWIN Semiconductor Corp |

| Section 1237 |

Grand China Air Co. Ltd. (GCAC) |

| Section 1237 |

Guizhou Space Appliance Co., Ltd. (SACO) |

| NS-CMIC |

Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Ltd (Hikvision) |

| Section 1237 |

Huawei Investment & Holding Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1237 |

Inner Mongolia First Machinery Group Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

Inspur Group Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1237 |

Jiangxi Hongdu Aviation Industry Co., Ltd. (HDAA) |

| Section 1260H |

Luokung Technology Corporation (LKCO) |

| Section 1237 |

Nanjing Panda Electronics Company Limited |

| NS-CMIC |

North Navigation Control Technology Co., Ltd. |

| NS-CMIC |

Panda Electronics Group Company, Ltd. |

| Section 1237 |

Proven Glory Capital Limited |

| NS-CMIC |

Proven Honour Capital Limited |

| NS-CMIC |

Semiconductor Manufacturing International (Beijing) Corporation |

| Section 1260H |

Semiconductor Manufacturing International (Shenzhen) Corporation |

| Section 1260H |

Semiconductor Manufacturing International (Tianjin) Corporation |

| Section 1260H |

Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) |

| Section 1237 |

Semiconductor Manufacturing South China Corporation |

| Section 1260H |

Shaanxi Zhongtian Rocket Technology Company Limited |

| NS-CMIC |

Sinochem Group Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1237 |

SMIC Holdings Limited |

| Section 1260H |

SMIC Hong Kong International Company Limited |

| Section 1260H |

SMIC Northern Integrated Circuit Manufacturing (Beijing) Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

SMIC Semiconductor Manufacturing (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. |

| Section 1260H |

Xiaomi Corporation |

| Section 1237 |

Zhonghang Electronic Measuring Instruments Company Limited (AVIC ZEMIC) |

| Section 1260H |

Trevor R. Jones is a research assistant at the Wisconsin Project. He contributes research to the Risk Report database with a focus on entities tied to China’s military and missile programs. Treston Chandler is a senior research associate at the Wisconsin Project. He is responsible for content research related to China and North Korea in the Risk Report database and oversees a project on North Korea sanctions.

Attachment:

![]() Sweeping U.S. Lists Seek to Restrict Trade and Investment that Support the Chinese Military

Sweeping U.S. Lists Seek to Restrict Trade and Investment that Support the Chinese Military

Footnotes:

[1] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, p. 14, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html.

[2] For an example of poor defense industry production in the Mao era, see: Peter Wood and Robert Stewart, “China’s Aviation Industry: Lumbering Forward,” China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, August 5, 2019, p. 23, available at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/Books/Lumbering_Forward_Aviation_Industry_Web_2019-08-02.pdf.

[3] Peter Wood and Robert Stewart, “China’s Aviation Industry: Lumbering Forward,” China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, August 5, 2019, pp. 24-26, available at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/Books/Lumbering_Forward_Aviation_Industry_Web_2019-08-02.pdf.

[4] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, pp. 15-16, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html.

[5] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation 2005, p. 40, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html.

[6] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, pp. xvii-xix, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html.

[7] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, pp. xvii-xix, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html.

[8] Peter Wood and Robert Stewart, “China’s Aviation Industry: Lumbering Forward,” China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, August 5, 2019, p. 26, available at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/Books/Lumbering_Forward_Aviation_Industry_Web_2019-08-02.pdf. For example, North Navigation Control Technology Co., Ltd. reported splitting its civilian businesses off into a separate entity in 2000. North Navigation Control Technology is on the NS-CMIC list and is a subsidiary of China North Industries Group Corporation, which is one of the major 10 defense conglomerates created in the wake of the 1999 reforms. See: “Company Profile,” North Navigation Control Technology Co., Ltd. World Wide Web site, available at http://bfdh.norincogroup.com.cn/col/col1027/index.html (in Chinese).

[9] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, p. 42, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html; Peter Wood and Robert Stewart, “China’s Aviation Industry: Lumbering Forward,” China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, August 5, 2019, p. 26, available at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/Books/Lumbering_Forward_Aviation_Industry_Web_2019-08-02.pdf.

[10] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, pp. xvii, 131, 141-142, 170, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html; Peter Wood and Robert Stewart, “China’s Aviation Industry: Lumbering Forward,” China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, August 5, 2019, p. 26, available at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/Books/Lumbering_Forward_Aviation_Industry_Web_2019-08-02.pdf.

[11] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, pp. 213-215, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html.

[12] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, pp. 231-233, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html.

[13] Evan S. Meideros, Roger Cliff, Keith Crane, and James C. Mulvenon, “A New Direction for China’s Defense Industry,” RAND Corporation, 2005, pp 231-235, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG334.html.

[14] “National Defense Science and Technology Key Laboratory Management Methods,” Harbin Institute of Technology Architecture School World Wide Web site, April 1, 2017, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20190522041912/http:/jzxy.hit.edu.cn/2018/0518/c10586a208951/page.htm (in Chinese); Alex Joske, “The China Defence Universities Tracker,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, November 25, 2019, available at https://www.aspi.org.au/report/china-defence-universities-tracker; “Notice of the State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense on Issuing the Detailed Rules for the Implementation of Special Incentive Subsidies for the Promotion of Military Technology (Trial),” State Administration of Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense World Wide Web site, November 7, 2017, available at http://www.sastind.gov.cn/n4235/c6797870/content.html (in Chinese).

[15] “Threats to the U.S. Research Enterprise: China’s Talent Recruitment Plans,” Staff Report, U.S. Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, November 18, 2019, p. 1, available at https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2019-11-18%20PSI%20Staff%20Report%20-%20China’s%20Talent%20Recruitment%20Plans.pdf; “National Defense Science and Technology Scholarship,” China Talent Tracker, Georgetown Center for Security and Emerging Technology World Wide Web site, available at https://chinatalenttracker.cset.tech/.

[16] Tai Ming Cheung, “Keeping Up with the Jundui: Reforming the Chinese Defense, Acquisition, Technology, and Industrial System,” in “Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms,” National Defense University Press, 2019, p. 586, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/Chairman-Xi/Chairman-Xi.pdf.

[17] MCF is a Xi-era policy that grew out of longstanding Chinese policies focused on the overlap of civilian and defense technologies since the reform era, including the Hu-era focus on “civil military integration” (CMI).

[18] Tai Ming Cheung, “Keeping Up with the Jundui: Reforming the Chinese Defense, Acquisition, Technology, and Industrial System,” in “Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms,” National Defense University Press, 2019, p. 600, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/Chairman-Xi/Chairman-Xi.pdf.

[19] Tai Ming Cheung, “Keeping Up with the Jundui: Reforming the Chinese Defense, Acquisition, Technology, and Industrial System,” in “Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms,” National Defense University Press, 2019, p. 586, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/Chairman-Xi/Chairman-Xi.pdf.

[20] “Ministry of Industry and Information Technology,” State Council of the People’s Republic of China World Wide Web site, August 20, 2014, available at http://english.www.gov.cn/state_council/2014/08/23/content_281474983035940.htm.

[21] “State Administration for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense,” State Council of the People’s Republic of China World Wide Web site, October 6, 2014, available at http://english.www.gov.cn/state_council/2014/10/06/content_281474992893468.htm.

[22] “State Administration for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense,” State Council of the People’s Republic of China World Wide Web site, October 6, 2014, available at http://english.www.gov.cn/state_council/2014/10/06/content_281474992893468.htm.

[23] “Findings of the Investigation Into China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, and Innovation Under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974,” Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, March 22, 2018, p. 96, available at https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/Section%20301%20FINAL.PDF.

[24] “State Administration for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense,” State Council of the People’s Republic of China World Wide Web site, October 6, 2014, available at http://english.www.gov.cn/state_council/2014/10/06/content_281474992893468.htm; Mark Stokes, Gabriel Alvarado, Emily Weinstein, and Ian Easton, “China’s Space and Counterspace Capabilities and Activities,” Project 2049 Institute and Pointe Bello, Report Prepared for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, March 30, 2020, p. 45, available at https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/China_Space_and_Counterspace_Activities.pdf; “Jilin University was Included in the 13th Five Year Plan of SASTIND and the Ministry of Education,” Jilin University World Wide Web site, July 6, 2016, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20191011004621/https://news.jlu.edu.cn/info/1021/42984.htm (in Chinese); “National Defense Science and Technology Key Laboratory Management Methods,” Harbin Institute of Technology Architecture School World Wide Web site, April 1, 2017, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20190522041912/http:/jzxy.hit.edu.cn/2018/0518/c10586a208951/page.htm (in Chinese).

[25] Most notably, Zhang Qingwei is the Party Secretary of Heilongjiang Province, Xu Dazhe is the Party Secretary of Hunan Province, Ma Xingrui is the Governor of Guangdong Province, and Chen Qiufa is the Party Secretary of Liaoning Province. Zhang served as COSTIND director and the other three served as SASTIND directors. See: “Zhang Kejian was Promoted to Director of SASTIND, All Four of His Predecessors are Provincial Leaders,” Sina News, May 22, 2018, available at http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2018-05-22/doc-ihawmaua7162737.shtml (in Chinese).

[26] Joel Wuthnow and Philip Saudners, “Chinese Military Reforms in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications,” National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, March 2017, p. 36, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-10.pdf; “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2020, p. 142, available at https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF; Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C. Saunders, “Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms,” National Defense University Press, 2019, p. 34, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/Chairman-Xi/Chairman-Xi.pdf; Dennis J. Blasko, “The Biggest Loser in Chinese Military Reforms: The PLA Army,” in “Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms,” National Defense University Press, 2019, pp. 373-374, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/Chairman-Xi/Chairman-Xi.pdf.

[27] Joel Wuthnow and Philip Saudners, “Chinese Military Reforms in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications,” National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, March 2017, p. 36, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-10.pdf; Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C. Saunders, “Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reforms,” National Defense University Press, 2019, pp. 5-7, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/Books/Chairman-Xi/Chairman-Xi.pdf; “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2020, p. 142, available at https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF.

[28] Joel Wuthnow and Philip Saudners, “Chinese Military Reforms in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications,” National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, March 2017, p. 36, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-10.pdf.

[29] Joel Wuthnow and Philip Saudners, “Chinese Military Reforms in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications,” National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, March 2017, p. 26, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-10.pdf

[30] Joel Wuthnow and Philip Saudners, “Chinese Military Reforms in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications,” National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, March 2017, p. 36, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-10.pdf.

[31] Joel Wuthnow and Philip Saudners, “Chinese Military Reforms in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges, and Implications,” National Defense University, Institute for National Strategic Studies, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, March 2017, p. 36, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-10.pdf.

[32] Mark Ashby, Caolionn O’Connell, Edward Geist, Jair Aguirre, Christian Curriden, and Jon Fujiwara, “Defense Acquisition in Russia and China,” RAND Corporation, 2021, p. vii, available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA113-1.html.

[33] “Hong Kong Executive Order: Licensing Policy Change for Hong Kong,” U.S. Department of State, Directorate of Defense Trade Controls, July 15, 2020, available at https://www.pmddtc.state.gov/ddtc_public?id=ddtc_search&q=Hong%20Kong; “Revision to the Export Administration Regulations: Suspension of License Exceptions for Hong Kong,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 85, No, 148, July 31, 2020, pp. 45998-46000, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-07-31/pdf/2020-16278.pdf.

[34] “Authorization To Impose License Requirements for Exports or Reexports to Entities Acting Contrary to the National Security or Foreign Policy Interests of the United States,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 73, No. 163, August 21, 2008, p. 49311, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2008-08-21/pdf/E8-19102.pdf.

[35] “Revisions to the Export Administration Regulations: Additions to the Entity List,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Export Administration, Federal Register, Vol. 62, No. 125, June 30, 1997, p. 35334, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1997-06-30/pdf/97-17146.pdf; “Missions and Goals,” China Academy of Engineering Physics World Wide Web site, available at https://www.caep.ac.cn/yq/smymb/index.shtml (in Chinese); “Historical Footprint,” China Academy of Engineering Physics World Wide Web site, available at https://www.caep.ac.cn/yq/lszj/index.shtml (in Chinese).

[36] “Addition of Certain Entities to the Entity List, Revision of Entries on the Entity List, and Removal of Entities From the Entity List,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 84, No. 157, August 14, 2019, p. 40237, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-08-14/pdf/2019-17409.pdf; “Addition of Entities to the Entity List, Revision of Certain Entries on the Entity List,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 85, No. 109, June 5, 2020, pp. 34495-34496, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-06-05/pdf/2020-10869.pdf; “Addition of Entities to the Entity List, Revision of Entry on the Entity List, and Removal of Entities From the Entity List,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 85, No. 246, December 22, 2020, pp. 83416-83417, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-12-22/pdf/2020-28031.pdf.

[37] “Revisions and Clarification of Export and Reexport Controls for the People’s Republic of China (PRC); New Authorization Validated End-User; Revision of Import Certificate and PRC End-User Statement Requirements,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 72, No. 117, June 19, 2007, pp. 33646-33647, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2007-06-19/pdf/E7-11588.pdf.

[38] “Frequently Asked Questions: Expansion of Export, Reexport, and Transfer (in-Country) Controls for Military End Use or Military End Users in the People’s Republic of China, Russia, or Venezuela,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, January 19, 2021, available at https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/pdfs/2566-2020-meu-faq/file; “Expansion of Export, Reexport, and Transfer (in-Country) Controls for Military End Use or Military End Users in the People’s Republic of China, Russia, or Venezuela,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 85, No. 82, April 28, 2020, pp. 23459, 23464, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-04-28/pdf/2020-07241.pdf.

[39] “Frequently Asked Questions: Expansion of Export, Reexport, and Transfer (in-Country) Controls for Military End Use or Military End Users in the People’s Republic of China, Russia, or Venezuela,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, January 19, 2021, available at https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/pdfs/2566-2020-meu-faq/file; “Expansion of Export, Reexport, and Transfer (in-Country) Controls for Military End Use or Military End Users in the People’s Republic of China, Russia, or Venezuela,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 85, No. 82, April 28, 2020, pp. 23459-23460, 23464, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-04-28/pdf/2020-07241.pdf.

[40] BIS may also add entities in Burma and Venezuela to the MEU List but, as of September 2021, it has not.

[41] “Addition of ‘Military End User’ (MEU) List to the Export Administration Regulations and Addition of Entities to the MEU List,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, Federal Register, Vol. 85, No. 247, December 23, 2020, p. 83793, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-12-23/pdf/2020-28052.pdf.

[42] “Supplement No. 7 to Part 744 – ‘Military End-User’ (MEU) List,” U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security, July 12, 2021, available at https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/regulations-docs/2714-supplement-no-7-to-part-744-military-end-user-meu-list/file.

[43] “Commerce Department Will Publish the First Military End User List Naming More Than 100 Chinese and Russian Companies,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Commerce, December 21, 2020, available at https://2017-2021.commerce.gov/news/press-releases/2020/12/commerce-department-will-publish-first-military-end-user-list-naming.html.

[44] “Executive Order 13959 of November 12, 2020 – Addressing the Threat From Securities Investments That Finance Communist Chinese Military Companies,” the White House, Federal Register, Vol. 85, No. 222, November 17, 2020, pp. 73185-73189, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-11-17/pdf/2020-25459.pdf.

[45] “DOD Releases List of Additional Companies, in Accordance with Section 1237 of FY99 NDAA,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Defense, August 28, 2020, available at https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/2328894/dod-releases-list-of-additional-companies-in-accordance-with-section-1237-of-fy/; “DOD Releases List of Additional Companies, In Accordance With Section 1237 of FY99 NDAA,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Defense, December 3, 2020, available at https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/2434513/dod-releases-list-of-additional-companies-in-accordance-with-section-1237-of-fy/; “DOD Releases List of Additional Companies, In Accordance with Section 1237 of FY99 NDAA,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Defense, January 14, 2021, available at https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/2472464/dod-releases-list-of-additional-companies-in-accordance-with-section-1237-of-fy/.

[46] 50 U.S.C. Section 1701, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title50/html/USCODE-2011-title50-chap35-sec1701.htm.

[47] “Executive Order 14032 of June 3, 2021 – Addressing the Threat From Securities Investments That Finance Certain Companies of the People’s Republic of China,” the White House, Federal Register, Vol. 86, No. 107, June 7, 2021, pp. 30145-30149, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-06-07/pdf/2021-12019.pdf.

[48] Transactions made solely to divest such securities are permitted until June 3, 2022. See: “Frequently Asked Questions: Chinese Military Company Sanctions,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control, available at https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/faqs/topic/5671.

[49] “Executive Order 14032 of June 3, 2021 – Addressing the Threat From Securities Investments That Finance Certain Companies of the People’s Republic of China,” the White House, Federal Register, Vol. 86, No. 107, June 7, 2021, pp. 30145-30149, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-06-07/pdf/2021-12019.pdf.

[50] “DOD Releases List of Chinese Military Companies in Accordance With Section 1260H of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021,” Press Release, U.S. Department of Defense, June 3, 2021, available at https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/2645126/dod-releases-list-of-chinese-military-companies-in-accordance-with-section-1260/.

[51] “Notice of the Removal of the Designation as Communist Chinese Military Companies Under the Strom Thurmond NDAA for FY99,” U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Acquisition and Sustainment), Federal Register, Vol. 86, No. 121, June 28, 2021, p. 33994, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-06-28/pdf/2021-13755.pdf.

[52] “William M. Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021,” H.R. 6395, U.S. Congress, pp. 578-579, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-116hr6395enr/pdf/BILLS-116hr6395enr.pdf.

[53] “William M. Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021,” H.R. 6395, U.S. Congress, pp. 578-579, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-116hr6395enr/pdf/BILLS-116hr6395enr.pdf.

[54] “William M. Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021,” H.R. 6395, U.S. Congress, pp. 578-579, available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-116hr6395enr/pdf/BILLS-116hr6395enr.pdf.